Rostra

41°53′33.5″N 12°29′04.6″E / 41.892639°N 12.484611°E

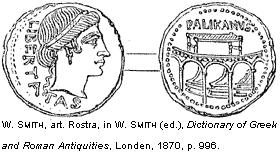

The Rostra of the early Republican era, as depicted on a Roman coin | |

| Lapis Niger | |

|---|---|

| Comitium | |

| Julius Caesar | |

| Roman Government | Political institutions |

| Social classes | Patrician, Senatorial class, equestrian class, plebeian, freedman |

| The Rostra was a specific platform for oration in ancient Rome. | |

The Rostra (Italian: Rostri) was a large platform built in the city of Rome that stood during the republican and imperial periods.[1] Speakers would stand on the rostra and face the north side of the Comitium towards the senate house and deliver orations to those assembled in between. It is often referred to as a suggestus or tribunal,[2] the first form of which dates back to the Roman Kingdom, the Vulcanal.[3][4]

It derives its name from the six rostra (plural of rostrum, a warship's ram) which were captured following the victory which ended the Latin War in the Battle of Antium in 338 BC and mounted to its side.[5] Originally, the term meant a single structure located within the Comitium space near the Roman Forum and usually associated with the Senate Curia. It began to be referred to as the Rostra Vetera ("Elder Rostra") in the imperial age to distinguish it from other later platforms designed for similar purposes which took the name "Rostra" along with its builder's name or the person it honored.

History

[edit]Magistrates, politicians, advocates and other orators spoke to the assembled people of Rome from this highly honored, and elevated spot.[6] Consecrated by the Augurs as a templum, the original Rostra was built as early as the 6th century BC. This Rostra was replaced and enlarged a number of times but remained in the same site for centuries.

In 338 BC the Rostra got its name when, following the defeat of Antium by the consul Gaius Maenius, the Antiate fleet was confiscated by Rome, of which the prows (literally rostra in Latin) of six ships were set upon the Rostra. Maenius paid for it out of his share of war booty. He also erected a victory column, the Columna Maenia, close to the Rostra.[7]

Julius Caesar rearranged the Comitium and Forum spaces and repositioned the Senate Curia at the end of the republican period. He moved the Rostra out of the Comitium.[8] This took away the commanding position the curia had held within the whole of the forum, having advanced extremely close to the Rostra during its last restoration. Augustus, his grand-nephew and first Roman emperor, finished what Caesar had begun, as well as expanded on it. This "New Rostra" became known as the Rostra Augusti. What remains in the excavated forum today, next to the Arch of Septimius Severus, has endured several restorations and alterations throughout its historical use. While a few different honorary names are attributed to those restorations, scholars, archeologists and the government of Italy recognise this platform as the "Rostra Vetera" encased inside the "Rostra Augusti".

The term rostrum, referring to a podium for a speaker is directly derived from the use of the term "Rostra". One stands in front of a Rostrum and one stands upon the Rostra. While, eventually, there were many rostra within the city of Rome and its republic and empire, then, as now, "Rostra" alone refers to a specific structure. Before the Forum Romanum, the Comitium was the first designated spot for all political and judicial activity and the earliest place of public assembly in the city. A succession of earlier shrines and altars is mentioned in early Roman writings as the first suggestum. It consisted of a shrine to the god Vulcan, that had two separate altars built at different periods. This early Etruscan mundus altar originally sat in front of a temple that would later be converted into the Curia Hostilia.

During the late Republic the rostra was used as a place to display the heads of defeated political enemies. Gaius Marius and consul Lucius Cornelius Cinna captured Rome in 87 BC and placed the head of the defeated consul, Gnaeus Octavius, on the Rostra.[9] The practice was continued by Sulla[10] and Mark Antony, who ordered that Cicero's hands and head be displayed on Caesar's Rostra after the orator's execution as part of the Proscription of 43 BC.[10]

Caesar spoke from the Rostra in 67 BC in a successful effort to pass, over the opposition of the Senate, a bill proposed by the tribune Aulus Gabinius (the lex Gabinia) creating an extraordinary command for Pompey to eliminate piracy in the Mediterranean.[11] Brutus and Cassius spoke from the Rostra to an unenthusiastic crowd in the Forum after the assassination of Caesar in 44 BC.[12] Millar comments that during the late Republic, when violence became a regular feature of public meetings, physical control and occupation of the Rostra became a crucial political objective.[13]

Tribal assemblies and tribunals

[edit]Until about 145 BC, the Comitium was the site for tribal assemblies (comitia tributa) at which important decisions were taken, magistrates were elected and criminal prosecutions were presented and resolved by tribal voting. Before an assembly, the convening magistrate, acting as augur, had to take the auspices in the inaugurated area (templum) on the Rostra from which he was to conduct the proceedings. If the omens were favorable and no other magistrate announced unfavorable omens, the magistrate summoned other magistrates and senators and directed a herald to summon the people. Heralds did so from the Rostra and from the City walls. During an assembly, magistrates, senators and private citizens spoke on pending legislation or for or against candidates for office. Before bills were presented for voting, a herald read them to the crowd from the Rostra. At the culmination of the process, the tribes were each called up to the templum on the Rostra to deliver their votes. After about 145 BC, the voting population of Rome grew too large for the Comitium, and tribal assemblies were then held at the opposite end of the Forum around the Temple of Castor, the steps of which served as an informal Rostra.[14][15][16]

The Rostra was also used for meetings of courts.[17] In Republican Rome, criminal prosecutions took place in the Forum either before a tribal assembly with a magistrate prosecuting (a procedure specified in the Twelve Tables and the normal mode of prosecution in the middle Republic) or in a jury-court (quaestio de repetundis) established by statute and presided over by a magistrate with a jury (after 70 BC) of about 50-75 jurors.[18] For trials held in the Comitium, the Rostra served as the tribunal upon which the magistrate sat in his curule chair with a small number of attendants. "This was enough in itself to establish a court, though it was supplemented by benches (subsellia) for the jurors, the parties to the case, and their supporters." The circle of onlookers (corona) either stood or sat on nearby steps.[19][20]

The original structure was built during the middle years of the Roman Republic in approximately 500 BC[10] It subsequently became known as the "Rostra" after the end of the Latin War in 338 BC when it was adorned by Gaius Maenius with naval rams (rostra) of ships captured at Antium as war trophies.[21]

The Rostra was located on the south side of the Comitium opposite the Curia Hostilia (the original Senate house), overlooking both the Comitium and the Roman Forum. In addition to the prows of captured ships, the Rostra bore a sundial[22] and, at various times, statues of such important political figures as Camillus, Sulla and Pompey.[13][23] Private citizens also erected a number of honorary columns and monuments on the Rostra and throughout the forum. At one point, the Senate threatened to have them removed if the donors did not do so themselves.[24]

Rostra Vetera

[edit]

In form, the original Rostra may have been a simple raised platform made of wood, similar to the Roman tribunal.[25] The Rostra had a curved form, possibly along the outer south rim of an amphitheatre. The structure was described by Christian Charles Josias Bunsen, based on his examination of two Roman coins depicting the Rostra, as "a circular building, raised on arches, with a stand or platform on the top bordered by a parapet; the access to it being by two flights of steps, one on each side. It fronted towards the Comitium, but later speakers often faced in the opposite direction to address larger audiences in the Forum. The Rostra Vetera's form has been in all the main points preserved in the ambones, or circular pulpits, of the most ancient churches, which also had two flights of steps leading up to them, one on the east side, by which the preacher ascended, and another on the west side, for his descent. Specimens of these old churches are still to be seen at Rome in the churches of San Clemente al Laterano and San Lorenzo fuori le Mura.[26]

As part of his reconstruction of the Roman Forum in 44 BC, Julius Caesar is believed to have moved the republican Rostra Vetera.[27] This Rostra, referred to as the "Rostra Nova" or "Caesarian Rostra", reused and incorporated nearly all of the original Rostra. Located on the southwest side of the new Julian Forum (Forum Iulium), the new Rostra was no longer subordinated to his new Senate House, the Curia Julia (still standing); Caesar had it placed on the central axis of the Forum, facing toward the open space. Left uncompleted at Caesar's death, Augustus finished and extended the new Rostra into a rectangle at the front, the dimensions being 28.8 metres (94 ft) long, 10 metres (33 ft) broad and 3.4 metres (11 ft) above the level of the forum pavement.[28] Traces of this Rostra can be seen today.

At the opposite end of the open Forum, the Temple of Caesar, completed by Augustus in 29 BC, included another Rostra at the front of its elevated base, facing the Caesarian Rostra. This Rostra was decorated with the rams from the Battle of Actium. John E. Stambaugh, professor of classics at Williams College, described the new arrangement as "a reflection of contemporary taste and the relentless Augustan desire for order."[23][29]

In contemporary news

[edit]In November 2008 heavy rain damaged the concrete covering that has been protecting the Vulcanal and its monuments located in the Imperial comitium space since the 1950s. This includes the stele accorded the name of "The Black Rock" or Lapis Niger. The marble and cement covering is a mix of the original black marble, said to have been used to cover the site by Sulla, and modern cement used to create the covering and keeping the marble in place.

Professor Angelo Bottini, Superintendent of Archeology in Rome, stated that an awning or tent covering is in place to protect the ancient relics until the covering is repaired, giving tourists of this millennium a look at the original suggestum for the first time in 50 years.[30]

Other known Rostra

[edit]In 29 BC Augustus ordered the construction of another Rostra in front of the Temple of Caesar, at the opposite end of the Forum Iulium from Caesar's Rostra. This was used as a tribunal and was adorned with the prows of galleys captured at the Battle of Actium.[23][31]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Nichols, Francis Morgan (1877). The Roman Forum. London. Longmans and Co. pp. 196. ISBN 978-1-4373-2096-1.

- ^ Richardson, Lawrence (1992). A new topographical dictionary of ancient Rome. The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 400. ISBN 978-0-8018-4300-6.

- ^ Lanciani, Rodolfo Amedeo (1900). The ruins and excavations of ancient Rome. Bell Publishing Company (1979). p. 278. ISBN 0-517-28945-8.

- ^ O'Connor, Charles James (1904). The Graecostasis of the Roman forum and its vicinity. University of Wisconsin. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-104-39141-6.

- ^ Murray, Michaēl, William Michael, Phōtios (1989). Octavian's campsite memorial for the Actian War. DIANE Publishing. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-87169-794-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Smith, Wayte, Marindin, William, William, George (1891). A dictionary of Greek and Roman antiquities. John Murray, Albemarle Street London. p. 567. ISBN 0-933029-82-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lomas, Kathryn (2018). The Rise of Rome: from the Iron Age to the Punic Wars. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press. p. 234.

- ^ Fodor's (22 March 2011). Fodor's Southern Italy. Random House Digital, Inc. pp. 62–. ISBN 978-0-307-92816-0. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ Goldsworthy, Adrian (22 September 2006). Caesar, Life of a Colossus By Adrian Goldsworthy. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300139198. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

- ^ a b c Vasaly, Ann (January 25, 1996). Representations. University of California Press. pp. 73. ISBN 978-0-520-20178-1.

- ^ Goldsworthy, Adrian (22 September 2006). Caesar, Life of a Colossus By Adrian Goldsworthy. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300139198. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

- ^ Goldsworthy, Adrian (2008). Caesar, Life of a Colossus. Yale University Press. pp. 509. ISBN 978-0-300-12689-1.

- ^ a b Millar, Fergus (2002). The Crowd in Rome in the Late Republic (Thomas Spencer Jerome Lectures). University of Michigan Press. p. 41. ISBN 0-472-08878-5. Retrieved 2009-06-01.

- ^ Lintott, Andrew William (1999). The Constitution of the Roman Republic. Oxford University Press. pp. 42–49. ISBN 0-19-815068-7.

- ^ Powell, J. G. F.; Paterson, Jeremy (2006). Cicero the Advocate. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-929829-7. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

- ^ Stambaugh, John E. (1988). The Ancient Roman City. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 104. ISBN 0-8018-3692-1. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

- ^ Lintott, Andrew William (1999). The Constitution of the Roman Republic. Oxford University Press. pp. 44–46. ISBN 0-19-815068-7.

- ^ Powell and Paterson, J. G. F and Jeremy (2004). Cicero the Advocate. Oxford University Press. pp. 32, 62, 68. ISBN 0-19-815280-9.

- ^ Powell and Paterson, J. G. F and Jeremy (2004). Cicero the Advocate. Oxford University Press. pp. 63. ISBN 0-19-815280-9.

- ^ Stambaugh, John E. (1988). The Ancient Roman City (Ancient Society and History). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-3692-1. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

- ^ "Rostra, William Smith, D.C.L., LL.D.:A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, John Murray, London, 1875". University of Chicago. Retrieved 2009-03-08.

- ^ Hannah, Robert (January 8, 2009). Time in Antiquity. Routledge; 1 edition. pp. 134. ISBN 978-0-415-33156-2.

- ^ a b c Hornblower and Spawforth, Simon and Antony (1949). The Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford University Press. pp. 1336. ISBN 0-19-866172-X.

- ^ Nichols, Francis Morgan (1877). The Roman Forum By Francis Morgan Nichols. Retrieved 2009-08-01.

- ^ Forbes, S. Russell (January 1, 1892). Rambles in Rome: An Archaeological and Historical Guide to the Museums, Gal. Thomas Nelson and Sons. pp. 43.

- ^ Quoted in Arnold, footnote 54, 274.

- ^ Sumi, Geoffrey (September 28, 2005). Ceremony and power: performing politics in Rome between Republic and Empire. University of Michigan Press; illustrated edition. pp. 78–80. ISBN 978-0-472-11517-4.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 755.

- ^ Stambaugh, John E. (1988). The Ancient Roman City. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 59. ISBN 0-8018-3692-1.

- ^ Owen, Richard (2008-11-23). "SIte of Romulus's murder to be tourist draw". London: Times Online. Retrieved 2009-07-01.[dead link]

- ^ Stambaugh, John E. (1988). The Ancient Roman City. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 118–119. ISBN 0-8018-3692-1.

Sources

[edit]- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2006). Caesar. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-12048-6.

- Hannah, Robert (2009). Time in Antiquity. City: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-33156-2.

- Hornblower, Simon (1996). The Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866172-X.

- Lanciani, Rodolfo (1979). The Ruins and Excavations of Ancient Rome. New York: Bell Pub. Co. ISBN 0-517-28945-8.

- Lexikon, Herder (1994). The Chiron Dictionary of Greek and Roman Mythology. Wilmette: Chiron Publications. ISBN 0-933029-82-9.

- Lintott, Andrew (1999). The Constitution of the Roman Republic. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-926108-3.

- Millar, Fergus (1998). The Crowd in Rome in the Late Republic. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-10892-1.

- Morstein-Marx, Robert (2004). Mass Oratory and Political Power in the Late Roman Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-82327-7.

- Nichols, Francis (2008) [1877]. The Roman Forum: a Topographical Study. City: Kessinger Publishing, LLC. ISBN 978-1-4373-2096-1.

- O'connor, Charles (2009). The Graecostasis of the Roman Forum and Its Vicinity. City: Kessinger Publishing, LLC. ISBN 978-1-104-39141-6.

- Paterson, Jeremy (2004). Cicero the Advocate. Oxford Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-815280-9.

- Richardson, Lawrence (1992). A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-4300-6.

- Stambaugh, John (1988). The Ancient Roman City. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-3692-1.

- Vasaly, Ann (1996). Representations. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20178-1.

External links

[edit]- Plan showing location in the Forum Romanum Archived 2019-09-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Coin depicting the ships prows attached to the rostra, and photograph showing the length of the rostra

- Further on the history of the rostra in the Forum Romanum

- Graphic reconstruction of the view of the rostra with the ships prows