Temple of the Dog was an American rock band that formed in Seattle, Washington, in 1990. It was conceived by vocalist Chris Cornell of Soundgarden as a tribute to his friend, the late Andrew Wood, lead singer of the bands Malfunkshun and Mother Love Bone. The lineup included Stone Gossard on rhythm guitar, Jeff Ament on bass guitar (both ex-members of Mother Love Bone and future members of Pearl Jam), Mike McCready (later Pearl Jam) on lead guitar, and Matt Cameron (Soundgarden and later Pearl Jam) on drums. Eddie Vedder appeared as a guest to provide some lead and backing vocals and later became lead vocalist of Pearl Jam. Pearl Jam's debut album, Ten, was released four months after Temple of the Dog's only studio album.

Temple of the Dog | |

|---|---|

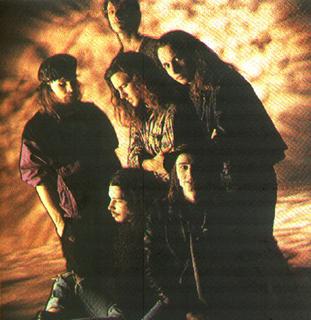

Early promo shot of Temple of the Dog. Top: Matt Cameron, 2nd row from left to right: Jeff Ament, Eddie Vedder, Stone Gossard, bottom from left to right: Chris Cornell, Mike McCready | |

| Background information | |

| Origin | Seattle, Washington, U.S. |

| Genres | Grunge · alternative rock |

| Years active | 1990–1992, 2016 (One-off reunions: 2003, 2009, 2011, 2014, 2016, 2019) |

| Labels | A&M |

| Spinoff of | Mother Love Bone, Soundgarden, Pearl Jam, Green River |

| Past members | |

| Website | templeofthedog |

The band released its only album, the self-titled Temple of the Dog, in April 1991 through A&M Records. The recording sessions took place in November and December 1990 at London Bridge Studio in Seattle, Washington, with producer Rakesh "Rick" Parashar. Although earning praise from music critics at the time of its release, the album was not widely recognized until 1992, when Vedder, Ament, Gossard, and McCready had their breakthrough with Pearl Jam (causing Temple of the Dog to sometimes be (retroactively) considered a supergroup). Cameron would later join Pearl Jam, serving as drummer since 1998, following Soundgarden's initial break-up in 1997, making the five members of Pearl Jam after that point identical to the members of Temple of the Dog other than Chris Cornell.

The band reformed and toured in 2016 to celebrate the 25th anniversary of their self-titled album. It was the only tour they ever undertook.

History

editFormation

editTemple of the Dog was started by Soundgarden frontman Chris Cornell, who had been a roommate of Phil Harris (lead singer / Spoons) and Andrew Wood, the lead singer of Malfunkshun and Mother Love Bone.[1] Wood died on March 19, 1990, of a heroin overdose, the day Phil picked up Cornell from the airport once he got back from a tour.[2] As he went on to tour Europe a few days later, he started writing songs in tribute to his late friend.[1] The result was two songs, "Reach Down" and "Say Hello 2 Heaven", which he recorded as soon as he returned home from touring.[1]

The recorded material was slow and melodic, musically different from the aggressive rock music of Soundgarden.[3] Cornell approached Wood's former Mother Love Bone bandmates Stone Gossard and Jeff Ament—who were still figuring out what to do after the death of their singer and lyricist—with the intention of releasing the songs as a single.[2] Ament described the collaboration as "a really good thing at the time" for Gossard and him that put them into a "band situation where we could play and make music."[2] The band's lineup was completed by the addition of Soundgarden (and later Pearl Jam) drummer Matt Cameron and future Pearl Jam lead guitarist Mike McCready, who was Gossard's childhood friend. They named themselves Temple of the Dog, a reference to a line in the lyrics of the Mother Love Bone song "Man of Golden Words".[1]

The band started rehearsing "Reach Down", "Say Hello 2 Heaven", and other songs that Cornell had written on tour prior to Wood's death, as well as re-working some existing material from demos written by Gossard, Ament, and Cameron.[4] One such demo became a song for two bands, recorded as "Footsteps" by Pearl Jam and "Times of Trouble" by Temple of the Dog.[5] The idea of doing covers of Wood's solo material also came up, but was abandoned quickly, as the band felt it would make people (including Wood's close friends and relatives[1]) think they were "exploiting his material."[2]

Recording

editThe release of a single was soon deemed a "stupid idea" by Cornell and dropped in favor of an EP or album.[1] The album was recorded in only 15 days, produced by the band themselves, along with Rick Parashar of London Bridge Studio.[1] Gossard described the recording process as a "non-pressure-filled" situation, as there were no expectations or pressure coming from the record company.[2] Eddie Vedder, who had flown up to Seattle from San Diego to audition to be the singer of Ament, Gossard, and McCready's new band, Mookie Blaylock (named for a basketball player, the band would later be renamed Pearl Jam), was at one of the Temple of the Dog rehearsals, and ended up providing backing vocals on a few songs,[6] with "Hunger Strike" becoming a duet between Cornell and Vedder. Cornell was still figuring out the vocals at practice, when Vedder stepped in and filled in the blanks, singing the low parts because he saw it was hard for Cornell.[7] As Cornell later described it: "He sang half of that song not even knowing that I'd wanted the part to be there and he sang it exactly the way I was thinking about doing it, just instinctively."[2][8] "Hunger Strike" became Temple of the Dog's breakout single. It was also Vedder's first featured vocal on a record.[9] In the 2011 documentary Pearl Jam Twenty, Vedder states: "That was the first time I heard myself on a real record. It could be one of my favorite songs that I've ever been on — or the most meaningful."[7]

Release and delayed success

editTemple of the Dog, the band's self-titled album, was released on April 16, 1991, through A&M Records and initially sold 70,000 copies in the United States.[4] Ament recalled requesting that A&M include a Pearl Jam sticker on the cover—as they had just picked their new name—because "it'll be a good thing for us", but they refused.[4] The album received favorable reviews,[10] but failed to chart. Critic Steve Huey of AllMusic later gave the album four-and-a-half stars out of five, stating that the "record sounds like a bridge between Mother Love Bone's theatrical '70s-rock updates and Pearl Jam's hard-rocking seriousness."[11] David Fricke of Rolling Stone wrote, in retrospect, that the album "deserves immortality."[12] The band members were pleased with the material, as it achieved its purpose; Cornell believed that "Andy really would have liked" the songs,[2] and Gossard also asserted that he thought Wood would be "blown away by the whole thing".[1] Soon after the album's release, Soundgarden and Pearl Jam embarked on recording their own albums, and the Temple of the Dog project was brought to a close, without a promotional tour for the album.

In the summer of 1992, the album received renewed attention. Although it had been released more than a year earlier, A&M Records realized that they had in their catalog what was essentially a collaboration between Soundgarden and Pearl Jam, who had both risen to mainstream attention in the months since the album's release with their respective albums, Badmotorfinger and Ten. A&M decided to reissue the album and promote "Hunger Strike" as a single, with an accompanying music video that had been previously filmed. The attention allowed both the album and single to chart on Billboard charts and resulted in a boost in album sales. The album ended up being among the 100 top-selling albums of 1992,[13] and it has sold more than a million copies, achieving a platinum certification by the Recording Industry Association of America.[14]

Subsequent events

editMcCready, Ament, Cameron, and Cornell later reunited under the name M.A.C.C. to record a cover of Jimi Hendrix's "Hey Baby (Land of the New Rising Sun)" for the 1993 tribute album Stone Free: A Tribute to Jimi Hendrix. The song has since been included as part of the band's live set. In a 2007 interview with Ultimate Guitar Archive, Cornell stated he would be open to a Temple of the Dog reunion, or "some collaboration with any combination of those guys".[6] He also revealed that Temple of the Dog was the reason he joined Audioslave, as the experience made him "keep an open mind" about collaborations with musicians from other bands.[6]

Live performances

editDuring their initial existence, the only time Temple of the Dog played a full one-hour set was while rehearsing and writing the material for the album. The band (with the exception of Vedder) performed in Seattle at the Off Ramp Café on November 13, 1990.[15] They also opened for Alice in Chains, following the short lived Seattle group Panic, on December 22, 1990, at the Moore Theatre in Seattle.

In the time since the album's release, the band has re-formed for short live one-off performances on occasions where both Soundgarden and Pearl Jam were performing. Temple of the Dog performed "Hunger Strike" on October 3, 1991, at the Foundations Forum in Los Angeles, California;[15] a three-song set on October 6, 1991, at the Hollywood Palladium in Hollywood for the RIP Magazine 5th anniversary party[16] (Temple of the Dog played after secret headlining act Spinal Tap[17]); and "Hunger Strike" on both August 14, 1992, at Lake Fairfax Park in Reston, Virginia, and September 13, 1992, at Irvine Meadows Amphitheater in Irvine, California (both shows were part of the Lollapalooza festival series in 1992).[18] The band also played "Reach Down" on the latter occasion.[18]

At a Pearl Jam show at the Santa Barbara Bowl in Santa Barbara, California, on October 28, 2003, Cornell joined the band on-stage, effectively reuniting Temple of the Dog (Cameron had been the drummer for Pearl Jam since 1998) for renditions of "Hunger Strike" and "Reach Down".[19] Cornell also performed Audioslave's "Like a Stone" and Chris Cornell's "Can't Change Me". The version of "Reach Down" recorded that night later appeared on Pearl Jam's 2003 fan club Christmas single. Pearl Jam has also been known to perform, on rare occasions, "Hunger Strike" live without Cornell.[20][21]

Cornell's post-Soundgarden band, Audioslave, added "All Night Thing", "Call Me a Dog", and "Hunger Strike" to its live set in 2005.[22] Additionally, Cornell added the aforementioned songs, plus "Pushin Forward Back", "Wooden Jesus", "Reach Down", and "Say Hello 2 Heaven", to his solo live set.[23][24][25]

On October 6, 2009, Cornell joined Pearl Jam onstage to perform "Hunger Strike" in Los Angeles, effectively reuniting Temple of the Dog once again.[26] After this, a fan group emerged on Facebook in April 2010 to encourage a 20th anniversary benefit reunion tour, to begin on April 16, 2011.[27]

During Labor Day weekend, 2011, Cornell joined Pearl Jam onstage at Alpine Valley in Wisconsin for PJ20 (Pearl Jam's twentieth anniversary celebration). On September 3, he joined them for a four-song set, which included the songs "Stardog Champion" (a Mother Love Bone cover with Cornell on vocals), "Say Hello 2 Heaven", "Reach Down", and "Hunger Strike". The next day, he joined them for "Hunger Strike", "Call Me a Dog", "All Night Thing", and "Reach Down" (which also included Glen Hansard, Dhani Harrison of Thenewno2, Davíd Garza, and Liam Finn).[28][29][30]

On both October 25 and 26, 2014, Cornell joined Pearl Jam onstage to perform "Hunger Strike" at Shoreline Amphitheater in Mountain View, California, during the 28th Annual Bridge School Benefit.[31] The October 26 concert marked the last time that Vedder and Cornell performed the song together.[32]

On January 30, 2015, Pearl Jam bandmates Stone Gossard, Jeff Ament, and Matt Cameron joined Chris Cornell and Mike McCready during the Mad Season Sonic Evolution Concert at Benaroya Hall with the Seattle Symphony. The group performed two songs from the album: "Reach Down" and "Call Me a Dog".[33]

Temple of the Dog finally officially toured in the fall of 2016 in celebration of the 25th anniversary of their self-titled album.[34][35] Vedder did not participate in the tour, citing "family commitments", so, at the band's concert at the Paramount Theatre in Seattle on November 21, 2016, the crowd sang his part in "Hunger Strike"[36] and Cornell dedicated the song to him.[37]

Discography

editStudio albums

edit| Year | Album details | Peak chart positions | Certifications (sales thresholds) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| US [38] |

CAN [39] | |||

| 1991 | Temple of the Dog | 5 | 11 | |

Singles

edit| Year | Song | Peak chart positions | Album | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US Main [42] |

US Alt [42] |

CAN [43] |

NZ [44] |

UK [45] | |||

| 1991 | "Hunger Strike" | 4 | 7 | 50 | 47 | 51 | Temple of the Dog |

| "Say Hello 2 Heaven" | 5 | — | — | — | — | ||

| "Pushin Forward Back" [US promo] | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| "—" denotes singles that did not chart. | |||||||

Music videos

edit- 1991 – "Hunger Strike"

- 2016 – "Hunger Strike" (2016 Mix)

Members

edit- Chris Cornell – lead vocals, rhythm guitar, banjo, harmonica

- Mike McCready – lead guitar, backing vocals

- Stone Gossard – rhythm guitar, backing vocals

- Jeff Ament – bass, backing vocals

- Matt Cameron – drums, backing vocals

- Eddie Vedder – backing vocals, co-lead vocals

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h Turman, Katherine. "Life Rules." RIP. October 1991

- ^ a b c d e f g Nicholls, Justin (April 14, 1991). "KISW 99.9 FM: Seattle, Radio Interview by Damon Stewart in The New Music Hour with Chris Cornell, Jeff Ament and Stone Gossard". Fivehorizons.com. Retrieved October 3, 2007.

- ^ O'Brien, Clare (June 27, 2007). "A conversation with Chris Cornell part 2". Chris Cornell Fan Page. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved October 3, 2007.

- ^ a b c Alden, Grant. "Requiem for a Heavyweight." Guitar World. July 1997

- ^ Cohen, Jonathan. "The Pearl Jam Q & A: Lost Dogs". Billboard. 2003.

- ^ a b c "Chris Cornell Open To Revisiting Temple". Ultimate Guitar Archive. September 14, 2007. Retrieved October 3, 2007.

- ^ a b Jeff Giles (April 16, 2016). "How Temple of the Dog Helped Members of Soundgarden and Pearl Jam Mourn a Friend". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- ^ Chad Childers (April 16, 2017). "26 Years Ago: Temple of the Dog Release Their Self-Titled Album". Loudwire. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- ^ David Fricke (May 29, 2017). "Chris Cornell: Inside Soundgarden, Audioslave Singer's Final Days". Rolling Stone. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "( Temple of the Dog > Biography )". AllMusic. Retrieved October 3, 2007.

- ^ Huey, Steve. "( Temple of the Dog > Review )". AllMusic. Retrieved October 3, 2007.

- ^ Fricke, David (December 14, 2000). "Temple of the Dog: Temple of the Dog". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 13, 2008. Retrieved October 3, 2007.

- ^ Lyons, James. Selling Seattle: Representing Contemporary Urban America. Wallflower, 2004. ISBN 1-903364-96-5, pp. 136

- ^ a b "Gold & Platinum Searchable Database – Search Results – Temple of the Dog". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- ^ a b "Pearl Jam: 1990/1991 Concert Chronology". Fivehorizons.com. Retrieved October 3, 2007.

- ^ "Rocklist.net...Kerrang! Page 2..." Rocklistmusic.co.uk.

- ^ "Spinal Tap Timeline". Spinaltapfan.com.

- ^ a b "Pearl Jam: 1992 Concert Chronology part 2". Fivehorizons.com. Retrieved October 3, 2007.

- ^ "Pearl Jam: 2003 Concert Chronology part 3". Fivehorizons.com. Retrieved October 3, 2007.

- ^ "Pearl Jam: 1996 Concert Chronology part 2". Fivehorizons.com. Retrieved October 3, 2007.

- ^ "Pearl Jam: 1998 Concert Chronology". Fivehorizons.com. Retrieved October 3, 2007.

- ^ bcd_71 (November 1, 2005). "Review of Audioslave @ Boston, MA". The Audioslave Fan Forum. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved August 25, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Brownlee, Clint (October 5, 2007). "Seattlest Misses Greyhound, Catches Chris Cornell's Hit Parade". Seattlest. Archived from the original on November 23, 2007. Retrieved November 8, 2007.

- ^ Zahlaway, Jon (April 20, 2007). "Live Review: Chris Cornell in Boston". LiveDaily. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved October 3, 2007.

- ^ Snelling, Nick (October 31, 2007). "Chris Cornell live at The Forum". BEAT magazine. Archived from the original on December 30, 2008. Retrieved November 8, 2007.

- ^ [1] Archived October 10, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Facebook". Facebook. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ "TEMPLE OF THE DOG Reunion At PEARL JAM's 20th-Anniversary Concert (Video) - Sep. 4, 2011". Blabbermouth.net. Archived from the original on February 1, 2013. Retrieved September 6, 2011.

- ^ Letkemann, Jessica. "Pearl Jam Caps PJ20 Fest With The Strokes, QOTSA, Chris Cornell All-Star Jam". Billboard.com. Retrieved September 6, 2011.

- ^ Kot, Greg (September 4, 2011). "Concert review: Pearl Jam at Alpine Valley Music Theatre". Chicago Tribune/ChicagoTribune.com.

- ^ "Temple of the Dog Reunite for 'Hunger Strike' at Bridge School Benefit". Rolling Stone. October 26, 2014. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ Andy Greene (May 23, 2017). "Flashback: Chris Cornell, Eddie Vedder's Final 'Hunger Strike' Duet". Rolling Stone. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ Casebeer, Glen. "McCready Makes Mad Season Show a Night Seattle Will Truly Never Forget". NorthWestMusicScene.com. Archived from the original on February 3, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ^ Roffman, Michael (July 20, 2016). "Temple of the Dog announce first-ever tour dates for 25th anniversary". consequence.net. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- ^ Maine, Samantha (November 6, 2016). "Watch Pearl Jam and Soundgarden supergroup Temple of Dog cover David Bowie". NME. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- ^ "Seattle celebrates Temple of the Dog — 25 years later". The Seattle Times. November 21, 2016. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ^ "Temple of the Dog - Hunger Strike - Seattle (November 21, 2016)". YouTube. November 22, 2016. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ^ "Temple of the Dog Chart History: Albums". Billboard. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ "Top Albums/CDs - Volume 56, No. 11, September 12, 1992". RPM. Archived from the original on January 22, 2009. Retrieved March 7, 2008.

- ^ "British album certifications – Temple of the Dog – Temple of the Dog". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ "Gold/Platinum Search "Temple of the Dog"". Music Canada. October 8, 1992. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ a b "Temple of the Dog Chart History: Singles". Billboard. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ "Canadian Charts — Hunger Strike". RPM. Archived from the original on January 22, 2009. Retrieved March 7, 2008.

- ^ "Discography Temple of the Dog". Hung Medien.

- ^ "UK Singles & Albums Official Charts Company — Temple of the Dog". Official Charts. Retrieved December 8, 2007.

Further reading

edit- Greene, Andy (September 30, 2016). "Temple of the Dog: An Oral History". Rolling Stone. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

External links

edit- Official website

- Temple of the Dog at AllMusic

- Temple of the Dog discography at Discogs