Pool of Radiance is a role-playing video game developed and published by Strategic Simulations, Inc (SSI) in 1988. It was the first adaptation of TSR's Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (AD&D) fantasy role-playing game for home computers, becoming the first episode in a four-part series of D&D computer adventure games. The other games in the "Gold Box" series used the game engine pioneered in Pool of Radiance, as did later D&D titles such as the Neverwinter Nights online game. Pool of Radiance takes place in the Forgotten Realms fantasy setting, with the action centered in and around the port city of Phlan.

| Pool of Radiance | |

|---|---|

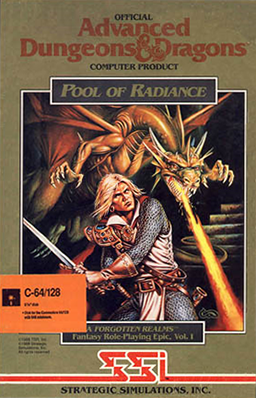

Cover art by Clyde Caldwell | |

| Developer(s) | Strategic Simulations Marionette (NES) |

| Publisher(s) | |

| Director(s) | Chuck Kroegel |

| Designer(s) | George MacDonald |

| Programmer(s) | Keith Brors Brad Myers |

| Artist(s) | Tom Wahl Fred Butts Darla Marasco Susan Halbleib |

| Composer(s) | Wally Beben (Amiga) David Warhol (C64) Seiji Toda (NES/PC-9800) Masayuki Kurinaga (PC98) |

| Series | Gold Box |

| Platform(s) | Amiga, Apple II, Commodore 64, MS-DOS, Mac, NES, PC-9800 |

| Release | June 1988: C64/128, MS-DOS 1989: Mac 1990: Amiga April 1992: NES |

| Genre(s) | Role-playing video game, tactical RPG |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Just as in traditional D&D games, the player starts by building a party of up to six characters, deciding the race, gender, class, and ability scores for each. The player's party is enlisted to help the settled part of the city by clearing out the marauding inhabitants that have taken over the surroundings. The characters move on from one area to another, battling bands of enemies as they go and ultimately confronting the powerful leader of the evil forces. During play, the player characters gain experience points, which allow them to increase their capabilities. The game primarily uses a first-person perspective, with the screen divided into sections to display pertinent textual information. During combat sequences, the display switches to a top-down "video game isometric" view.[1]

Generally well received by the gaming press, Pool of Radiance won the Origins Award for "Best Fantasy or Science Fiction Computer Game of 1988". Some reviewers criticized the game's similarities to other contemporary games and its slowness in places, but praised the game's graphics and its role-playing adventure and combat aspects. Also well-regarded was the ability to export player characters from Pool of Radiance to subsequent SSI games in the series.

Gameplay

editPool of Radiance is based on the same game mechanics as the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons rule set.[2] As in many role-playing games (RPGs), each player character in Pool of Radiance has a character race and a character class, determined at the beginning of the game. Six races are offered, including elves and halflings, as well as four classes (fighter, cleric, magic-user, and thief).[2] Non-human characters have the option to become multi-classed, which means they gain the capabilities of more than one class,[3] but advance in levels more slowly.[citation needed] During character creation, the computer randomly generates statistics for each character, although the player can alter these attributes.[4] The player also chooses each character's alignment, or moral philosophy; while the player controls each character's actions, alignment can affect how NPCs view their actions.[3] The player can then customize the appearance and colors of each character's combat icon.[2] Alternatively, the player can load a pre-generated party to be used for introductory play.[5] These characters are combined into a party of six or less, with two slots open for NPCs.[6] Players create their own save-game files, assuring their characters can continue regardless of events in the game. The MS-DOS version can be copied to the hard drive. Other computer systems, such as the Commodore 64, require a separate disk for saved games.[7]

The game's exploration mode uses a three-dimensional first-person perspective, with a rectangle in the top left of the screen displaying the party's current view; the rest of the screen displays text information about the party and the area.[8] During gameplay, the player accesses menus to allow characters to use objects; trade items with other characters; parley with enemies; buy, sell, and pool the characters' money; cast spells, and learn new magic skills. Players can view characters' movement from different angles, including an aerial view.[9] The game uses three different versions of each sprite to indicate differences between short-, medium-, and long-range encounters.[10]

In combat mode, the screen switches to a top-down perspective with dimetric projection, where the player chooses what actions the characters will take in each round; these actions occur immediately, instead of happening after all commands are issued as is standard in some RPGs.[8] Optionally, the player can let the computer choose character moves for each round.[9] Characters and monsters may make an extra attack on a retreating enemy that moves next to them.[8] If a character's hit points (HP) go below zero, they must be bandaged by another character or the wounded character will die.[8] The game contains random encounters, and game reviewers for Dragon magazine observed that random encounters seem to follow standard patterns of encounter tables in pen and paper AD&D game manuals. They also observed that the depictions of monsters confronting the party "looked as though they had jumped from the pages of the Monster Manual".[7]

Different combat options are available to characters based on class: fighters can use melee or ranged weapons; magic-users can cast spells; thieves are able to "back-stab" an opponent by strategically positioning themselves.[8] As fighters progress in level, they can attack more than once in a round, and they also gain the ability to "sweep" enemies, effectively attacking each nearby low-level creature in the same turn.[11] Magic-users and clerics are allowed to memorize and cast a set number of spells each day. Once cast, a spell must be memorized again before reuse. The process requires hours of inactivity for all characters, during which they rest in a camp; this also restores lost hit points to damaged characters.[8] This chore of memorizing spells each night significantly added to the amount of game management required by the player.[12]

As characters defeat enemies, they gain experience points (XP). After gaining enough XP, the characters "train up a level" to become more powerful.[2] This training is purchased in special areas within the city walls.[3] In addition to training, mages can learn new spells by transcribing them from scrolls found in the unsettled areas.[8] Defeated enemies in these areas also contain items such as weapons and armor, which characters can sell to city stores.[7]

Setting

editPool of Radiance takes place in the Forgotten Realms fantasy world, in and around the city of Phlan. This is located on the northern shore of the Moonsea along the Barren River, between Zhentil Keep and Melvaunt.[10] The party begins in the civilized section of "New Phlan" that is governed by a council. This portion of the city hosts businesses, including shopkeepers that sell holy items for worshippers at each temple, a jewelry shop, and retailers who provide arms and armor. A party can also contract with the clerk of the city council for various commissions; proclamations posted on the walls within City Hall offer pieces of useful information in the form of coded clues which can be deciphered using the included Adventurer's Journal.[7]

Phlan has three temples, each dedicated to different gods. Each temple can heal wounded, poisoned, or afflicted characters, and can restore deceased characters to life for a high price. The party can also visit the hiring hall and hire an experienced NPC adventurer to accompany the party.[7] Encounters with NPCs in shops and taverns offer valuable information.[13] Listening to gossip in taverns can be helpful to characters, although some tavern tales are false and lead characters into great danger.[3]

Plot

editThe ancient trade city of Phlan has fallen into impoverished ruin. Now only a small portion of the city remains inhabited by humans, who are surrounded by evil creatures. To rebuild the city and clean up the Barren River, the city council of New Phlan has decided to recruit adventurers to drive the monsters from the neighboring ruins. Using bards and publications, they spread tales of the riches waiting to be recovered in Phlan, which draws the player's party to these shores by ship.[14][15]

At the start of the game, the adventurers' ship lands in New Phlan, and they receive a brief but informative tour of the civilized area.[11] They learn that the city is plagued with a history of invasions and wars and has been overtaken by a huge band of humanoids and other creatures. Characters hear rumors that a single controlling element is in charge of these forces.[13] The characters begin a block-by-block quest to rid the ruins of monsters and evil spirits.[6]

Beyond the ruins of old Phlan, the party enters the slum area—one of two quests available right away to new parties. This quest involves the clearing of the slum block and allows a new party to quickly gain experience. The second quest is to clear out Sokol Keep, located on Thorn Island.[7] This fortified area is inhabited by the undead, which can only be defeated with silver weapons and magic.[7] The characters' adventure is later expanded to encompass the outlying areas of the Moonsea region.[6] Eventually, the player learns that an evil spirit named Tyranthraxus, who has possessed an ancient dragon, is at the root of Phlan's problems.[8] The characters fight Tyranthraxus the Flamed One in a climactic final battle.[6]

Development

editPool of Radiance was the first official game based on the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons rules.[2] The scenario was created by TSR designers Jim Ward, David Cook, Steve Winter, and Mike Breault, and coded by programmers from Strategic Simulations, Inc's Special Projects team.[16] The section of the Forgotten Realms world in which Pool of Radiance takes place was intended to be reserved for development solely by SSI.[15] The game was created on Apple II and Commodore 64 computers, taking one year with a team of thirty-five people.[2] This game was the first to use the game engine later used in other SSI D&D games known as the "Gold Box" series.[10][17][18] The SSI team developing the game was led by Chuck Kroegel.[3] Kroegel stated that the main challenge with the development was interpreting the AD&D rules to an exact format. Developers also worked to balance the graphics with gameplay to provide a faithful AD&D feel, given the restrictions of a home computer. In addition to the core AD&D manuals, the books Unearthed Arcana and Monster Manual II were also used during development.[2] The images of monsters were adapted directly from the Monster Manual book.[19] The game was originally programmed by Keith Brors and Brad Myers, and it was developed by George MacDonald.[20] The game's graphic arts were by Tom Wahl, Fred Butts, Darla Marasco, and Susan Halbleib.[20]

Pool of Radiance was released in June 1988;[15] it was initially available on the Commodore 64, Apple II series and IBM PC compatible computers.[17] A version for the Atari ST was also announced.[5] The Macintosh version was released in 1989.[17] The Macintosh version featured a slightly different interface and was intended to work on black-and-white Macs like the Mac Plus and the Mac Classic. The screen was tiled into separate windows including the game screen, text console, and compass. Graphics were monochrome and the display window was relatively small compared to other versions. The Macintosh version featured sound, but no music. The game's Amiga version was released two years later.[4] The PC 9800 version 『プール・オブ・レイディアンス』 in Japan was fully translated (like the Japanese Famicom version) and featured full-color graphics. The game was ported to the Nintendo Entertainment System under the title Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Pool of Radiance, released in April 1992.[21] The NES version was the only version of the game to feature a complete soundtrack, which was composed by Seiji Toda, as he was signed to the publisher, Pony Canyon's record label at the time.[citation needed] The same soundtrack can be found on the PC-9801 version.[citation needed] The Amiga version also features some extra music, while most other ports contain only one song that plays at the title screen.[citation needed]

The original Pool of Radiance game shipped with a 28-page introductory booklet, which describes secrets relating to the game and the concepts behind it. The booklet guides players through the character creation process, explaining how to create a party. The game also included the 38-page Adventurer's Journal, which provides the game's background. The booklet features depictions of fliers, maps, and information that characters see in the game.[3]

The DOS, Macintosh and Apple II versions of Pool of Radiance include a 2-ply code wheel for translating Espruar (the elvish language) and Dethek (the dwarven language) runes into English.[22] Some Dethek runes have multiple different translations.[3][23][24][25] After the title screen, a copy protection screen is displayed consisting of two runes and a line of varying appearance (a dotted line, a dashed line, or a line with alternating dots and dashes) which correspond to markings on the code wheel.[23] The player is prompted to enter a five or six character code which corresponds to a five or six character word. In the case of a five character word, there is a number at the beginning of the word which is not entered.[24][25] Under the lines on the wheel are slots which reveal English letters, the coded English word being determined by lining up the runes, matching the correct line appearance, and then entering the word revealed on the code wheel.[24][25] If the player enters an incorrect code three times, the game closes itself.[23] In the DOS version of Pool of Radiance, the code wheel is also used for some in-game puzzles. For example, in Sokol Keep the player discovers some parchment with elvish runes on it that require use of the code wheel to decipher; this is optional however, but may be used to avoid some combat with undead if the decoded words are said to them.[23] In the NES version, the elvish words are given to the player deciphered without the use of the code wheel, as the NES release did not include a code wheel.

Re-release

editGOG.com released Pool of Radiance and many Gold Box series games digitally on August 20, 2015, as a part of Forgotten Realms: The Archives-Collection Two.[26] Steam released Pool of Radiance in 2022.[27]

Reception

edit| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| Dragon | (DOS) |

| Amiga Action | 79%[4] (Amiga) |

| Commodore User | 9/10[13] (C64) |

| The Games Machine | 89%[5] (C64) |

| Zzap!64 | 80%[9] (C64) |

| Publication | Award |

|---|---|

| Origins Award | Best Fantasy or Science Fiction Computer Game of 1988[28] |

SSI sold 264,536 copies of Pool of Radiance for computers in North America, three times that of Heroes of the Lance, an AD&D-licensed action game SSI also released that year. It became by far the company's most successful game up to that time; even its hint book outsold any earlier SSI game.[29] It spawned a series of games, which combined to sell above 800,000 copies worldwide by 1996.[30]

In Computer Gaming World's preview of Pool of Radiance in July 1988, the writer noted a "sense of deja vu" in the similarity of the game's screen to previous computer RPGs. For example, the three-dimensional view like a maze in the upper-left window was similar to Might & Magic or Bard's Tale, both released in the mid-1980s. The window that included a listing of characters was featured in 1988's Wasteland; and the usage of one active character as a representation of the entire party was part of Ultima V. The reviewer also noted that the design approach for game play was "closer to SSI's own Wizard's Crown adventures than to the other games in the genre".[31]

Pool of Radiance received positive reviews. G.M. called the game's graphics "good" and praised its role-playing and combat aspects. They felt that "roleplayers will find Pools is an essential purchase, but people who are solely computer games oriented may hesitate before buying it [...] it will be their loss".[2] Tony Dillon from Commodore User gave it a score of 9 out of 10; the only complaint was a slightly slow disk access, but the reviewer was impressed with the game's features, awarding it a Commodore User superstar and proclaiming it "the best RPG ever to grace the C64, or indeed any other computer".[13] Issue #84 of the British magazine Computer + Video Games rated the game highly, saying that "Pools is a game which no role player or adventurer should be without and people new to role playing should seriously consider buying as an introductory guide".[3] Another UK publication, The Games Machine, gave the game an 89% rating. The reviewer noted that the third-person arcade style combat view is a "great improvement" for SSI, as they would "traditionally incorporate simplistic graphics in their role-playing games". The reviewer was critical that Pool of Radiance was "not original in its presentation" and that the colors were "a little drab", but concluded that the game is "classic Dungeons & Dragons which SSI have recreated excellently".[5] A review from Zzap was less positive, giving the game a score of 80%. The reviewer felt that the game required too much "hacking, slicing and chopping" without enough emphasis on puzzle solving. The game was awarded 49% for its puzzle factor.[9]

Jim Trunzo reviewed Pool of Radiance in White Wolf #16 (June/July, 1989), rating it a 4 out of 5 and stated that "Overall, Pool of Radiance must be termed a success. It is beautiful to look at, true to its AD&D roots, boasts features like automapping and excellent documentation, and has a strong theme to motivate gamers."[32]

Three reviewers for Computer Gaming World had conflicting reactions. Ken St. Andre—designer of the Tunnels & Trolls RPG—approved of the game despite his dislike of the D&D system, praising the art, the mixture of combat and puzzles, and surprises. He concluded as "take it from a 'rival' designer, Pool of Radiance has my recommendation for every computer fantasy role-playing gamer". Tracie Forman Hicks, however, opined that over-faithful use of the D&D system left it behind others like Ultima and Wizardry. She also disliked the game's puzzles and lengthy combat sequences.[33] Scorpia also disliked the amount of fighting in a game she otherwise described as a "well-designed slicer/dicer", concluding that "patience (possibly of Job) [is] required to get through this one".[34][35] Shay Addams from Compute! stated that experienced role-playing gamers "won't find anything new here", but recommended it to those who "love dungeons, dragons, and drama".[36] In their March 1989 "The Role of Computers" column in Dragon magazine #143, Hartley, Patricia, and Kirk Lesser gave Pool of Radiance a three-page review. They praised it as "the first offering that truly follows AD&D game rules" and advised readers to "rush out to your local dealer and buy Pool Of Radiance", considering it SSI's flagship product and speculating that it would "undoubtedly bring thousands of computer enthusiasts into the adventure-filled worlds of TSR". The Lessers stated that the Commodore version would be nearly unplayable without the built-in SSI fast loader; conversely, they found that the DOS version was so fast—twice the speed of the Commodore version when using [[EGA graphics—that the Lessers had to slow the computer to read all the on-screen messages.[7]

Alex Simmons, Doug Johns, and Andy Mitchell reviewed the Amiga version of Pool of Radiance for Amiga Action magazine in 1990, giving it a 79% overall rating. Mitchell preferred the game Champions of Krynn, which had been released by the time the Amiga version of Pool of Radiance became available; he felt that Pool of Radiance was "more of the same" when compared to Champions, but was less playable and with more limited actions for players. Simmons felt that Pool of Radiance looked primitive and seemed less polished when compared with Champions of Krynn; he felt that although Pool was not up to the standard of Champions, he said it was still "a fine little game". Johns, on the other hand, felt that Pool of Radiance was well worth the wait, considering it very user-friendly despite being less polished than Champions of Krynn.[4]

Lisa Stevens reviewed the Macintosh version of Pool of Radiance in White Wolf #26 (April/May, 1991), rating it a 5 out of 5 and stated that "I can't recommend Pool of Radiance highly enough to Macintosh users, and especially players who are familiar with the AD&D game system. SSI has thrown down the gauntlet for the other computer game companies who are catering to the growing Macintosh market. I hope the other companies take up the challenge and produce games of this caliber."[37]

Pool of Radiance was well received by the gaming press and won the Origins Award for Best Fantasy or Science Fiction Computer Game of 1988.[28] For the second annual "Beastie Awards" in 1989, Dragon's readers voted Pool of Radiance the most popular fantasy role-playing game of the year, with Ultima V as the runner-up. The Apple II version was the most popular format, the PC DOS/MS-DOS version came in a close second, and the Commodore 64/128 version got the fewest votes. The primary factor given for votes was the game's faithfulness to the AD&D system as well as the game's graphics and easy-to-use user interface to activate commands.[38] Pool of Radiance was also selected for the RPGA-sponsored Gamers' Choice Awards for the Best Computer Game of 1989.[39] In 1990 the game received the fifth-highest number of votes in a survey of Computer Gaming World readers' "All-Time Favorites".[40]

Allen Rausch, writing for GameSpy's 2004 retrospective "A History of D&D Video Games", concluded that although the game "certainly had its flaws (horrendous load times, interface weirdness, and a low-level cap among others), it was a huge, expansive adventure that laid a good foundation for every Gold Box game that followed".[41] In 1994, PC Gamer US named Pool of Radiance the 43rd best computer game ever.[42]

IGN ranked Pool of Radiance No. 3 on their list of "The Top 11 Dungeons & Dragons Games of All Time" in 2014.[43] In March 2008, Dvice.com listed Pool of Radiance among its 13 best electronic versions of Dungeons & Dragons. The contributor felt that "the Pool of Radiance series set the stage for Dungeons & Dragons to make a major splash in the video game world".[44] Ian Williams of Paste rated the game #5 on his list of "The 10 Greatest Dungeons and Dragons Videogames" in 2015.[45]

Sequels and related works

editIn November 1989, a novelization of the game, also called Pool of Radiance, was published by James Ward and Jane Cooper Hong, published by TSR. It is set in the Forgotten Realms setting based on the Dungeons & Dragons fantasy role-playing game. Dragon described the novel's plot: "Five companions find themselves in the unenviable position of defending the soon-to-be ghost town against a rival possessing incredible power".[46] The book was the first in a trilogy, followed by Pools of Darkness and Pool of Twilight.

Pool of Radiance was the first in a four-part series of computer D&D adventures set in the Forgotten Realms campaign setting. The others were released by SSI one year apart: Curse of the Azure Bonds (1989), Secret of the Silver Blades (1990), and Pools of Darkness (1991).[8] The 1989 game Hillsfar was also created by SSI but was not a sequel to Pool of Radiance. Hillsfar is described instead, by the reviewers from Dragon, as "a value-added adventure for those who would like to take a side trip while awaiting the sequel".[47] A player can import characters from Pool of Radiance into Hillsfar, although the characters are "reduced to their basic levels" and do not retain any weapons or magic items. Original Hillsfar characters cannot be exported to Pool of Radiance, but they can be exported to Curse of the Azure Bonds.[47] A review for Curse of the Azure Bonds in Computer Gaming World noted that "you can transfer your characters from Pool of Radiance and it's a good idea to do so. It will give you a headstart in the game".[48]

GameSpot declared that Pool of Radiance, with its detailed art, wide variety of quests and treasure, and tactical combat system, and despite the availability of only four character classes and the low character level cap, "ultimately succeeded in its goal of bringing a standardized form of AD&D to the home computer, and laid the foundation for other future gold box AD&D role-playing games".[6] Scott Battaglia of GameSpy said Pool of Radiance is "what many gamers consider to be the epitome of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons RPGs. These games were so great that people today are using MoSlo in droves to slow down their Pentium III-1000 MHz enough to play these gems".[11]

The 1988 Dungeons & Dragons role-playing game module Ruins of Adventure was produced using the same adventure scenario as Pool of Radiance, using the same plot, background, setting, and many of the same characters as the computer game. The module thus contains useful clues to the successful completion of the computer missions.[49] Ruins of Adventure contains four linked miniscenarios, which form the core of Pool of Radiance.[50] According to the editors of Dragon magazine, Pool of Radiance was based on Ruins of Adventure, rather than the module being based on the computer game,[51] but Mike Breault stated in a 2021 interview that TSR chose him, Winter, Cook, and Ward to work on the design and writing for Pool of Radiance, indicating that the material was originally created for the game.[52]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Top 100 RPGs of All Time". IGN. Archived from the original on September 15, 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Advanced Dungeons & Dragons". G.M. The Independent Fantasy Roleplaying Magazine. Vol. 1, no. 1. Croftward. September 1988. pp. 18–20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wayne (October 1988). "Reviews". Computer + Video Games. No. 84. pp. 18–19, 21. ISBN 0-8247-8502-9.

- ^ a b c d Simmons, Alex; Johns, Doug; Mitchell, Andy (November 1990). "US Gold/SSI - Pool of Radiance". Amiga Action. No. 14. pp. 72–73.

- ^ a b c d "Pool Your Resources". The Games Machine. No. 12. November 1988. p. 69.

- ^ a b c d e "GameSpot's History of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons". GameSpot. Retrieved 5 August 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lesser, Hartley; Lesser, Patricia; Lesser, Kirk (March 1989). "The Role of Computers". Dragon. No. 143. pp. 76–78.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Barton, Matt (23 February 2007). "The History of Computer Role-Playing Games Part 2: The Golden Age (1985–1993)". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 26 March 2009.

- ^ a b c d "Pool of Radiance". Zzap. No. 44. December 1988. p. 127. Retrieved 21 February 2008.

- ^ a b c DeMaria, Rusel; Johnny L. Wilson (2003). "The Wizardry of Sir-Tech". High Score!: The Illustrated History of Electronic Games. McGraw-Hill Osborne Media. p. 161. ISBN 0-07-222428-2. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ^ a b c Battaglia, Scott. "The GameSpy Hall of Fame". GameSpy. Archived from the original on 11 December 2004. Retrieved 5 August 2009.

- ^ Tresca, Michael J. (2010), The Evolution of Fantasy Role-Playing Games, McFarland, p. 142, ISBN 978-0786458950

- ^ a b c d Dillon, Tony (October 1988). "Pool of Radiance". Commodore User. pp. 34–35.

- ^ E, Dan (January 19, 1989). "Enter the pool of radiance". The New Straits Times. Retrieved 2011-06-24.

- ^ a b c Ward, James M. (May 1988). "The Game Wizards". Dragon. No. 133. p. 42. Retrieved 19 June 2024.

- ^ "The Envelope, Please!". Dragon. No. 149. September 1989. pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b c Deci, T.J. "Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Pool of Radiance". Allgame. Archived from the original on 14 November 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ Buchanan, Levi (March 6, 2008). "Dungeons & Dragons Classic Videogame Retrospective". IGN. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ^ Cover, Jennifer Grouling (2010). The Creation of Narrative in Tabletop Role-Playing Games. McFarland. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-7864-4451-9.

- ^ a b "Pool of Radiance". MobyGames. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ "Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Pool of Radiance". gamespot UK. Archived from the original on 2008-10-13.

- ^ "Pool of Radiance - Translation Wheel". www.oldgames.sk. Retrieved 2024-08-11.

- ^ a b c d Pool of Radiance (1988). DOS. Strategic Simulations, Inc. Strategic Simulations, Inc.

- ^ a b c Pool of Radiance DOS Manual. Strategic Simulations. 1988.

- ^ a b c Pool of Radiance Macintosh Manual. Strategic Simulations. 1989.

- ^ Jordan Erica Webber (Aug 20, 2015). "Forgotten Realms: The Archives brings 13 D&D classics to GOG". PC Gamer.

- ^ "Pool of Radiance on Steam". store.steampowered.com. Retrieved 2023-11-29.

- ^ a b "1988 List of Winners". Academy of Adventure Gaming, Arts & Design. Origins Games Fair. Archived from the original on May 7, 2008. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- ^ Maher, Jimmy (2016-03-18). "Opening the Gold Box, Part 3: From Tabletop to Desktop". The Digital Antiquarian. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ "SSI Corporate Background". SSI Online. Strategic Simulations, Inc. Archived from the original on November 19, 1996. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ Wilson, Johnny L. (July 1988). "Reflections on a "Pool of Radiance"". Computer Gaming World. No. 49. pp. 20–21.

- ^ Trunzo, Jim (June–July 1989). "The Silicon Dungeon". White Wolf Magazine. No. 16. pp. 49–50.

- ^ St. Andre, Ken; Hines, Tracie Forman (December 1988). "Mirror Images in a "Pool of Radiance"". Computer Gaming World. p. 28. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ Scorpia (October 1991). "C*R*P*G*S / Computer Role-Playing Game Survey". Computer Gaming World. p. 16. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ^ Scorpia (October 1993). "Scorpia's Magic Scroll Of Games". Computer Gaming World. pp. 34–50. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ Addams, Shay (February 1989). "Pool of Radiance". Compute!. p. 62. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- ^ Stevens, Lisa (April–May 1991). "The Silicon Dungeon". White Wolf Magazine. No. 26. p. 62.

- ^ Lesser, Hartley; Lesser, Patricia & Lesser, Kirk (November 1989). "The Beastie Knows Best". Dragon. No. 151. p. 36.

- ^ "The Gamers Have Chosen!". Dragon. No. 151. November 1989. p. 85.

- ^ "CGW Readers Select All-Time Favorites". Computer Gaming World. January 1990. p. 64. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ^ Rausch, Allen (August 15, 2004). "A History of D&D Video Games". GameSpy. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- ^ "Top 40: The Best Games of All Time; The Ten Best Games that Almost Made the Top 40". PC Gamer US. No. 3. August 1994. p. 42.

- ^ "The Top 11 Dungeons & Dragons Games of All-Time". IGN. February 5, 2014. Retrieved May 20, 2018.

- ^ Hall, Kevin (18 March 2008). "The 13 best electronic versions of Dungeons & Dragons". Dvice.com. Archived from the original on 6 August 2012. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ^ "The 10 Greatest Dungeons and Dragons Videogames". Paste. April 27, 2015. Retrieved May 20, 2018.

- ^ Kirchoff, Mary (January 1989). "The Game Wizards". Dragon. No. 141. p. 69.

- ^ a b Hartley, Patricia & Kirk Lesser (July 1989). "The Role of Computers". Dragon. No. 147. pp. 78–79.

- ^ Scorpia (September 1989). "Curse of The Azure Bonds". Computer Gaming World. No. 63. pp. 8–9, 46. Archived from the original on 2011-07-23.

- ^ Ward, James; Cook, David "Zeb"; Winter, Steve; Breault, Mike (1988). Ruins of Adventure. TSR. p. 2. ISBN 0-88038-588-X.

- ^ Schick, Lawrence (1991). Heroic Worlds: A History and Guide to Role-Playing Games. Prometheus Books. p. 113. ISBN 0-87975-653-5.

- ^ "The Role of Computers". Dragon. No. 159. July 1990. p. 53.

- ^ Breault, Michael (2021-05-13). "Making Pool of Radiance". Oral History of Video Games. Retrieved 2023-08-08.

External links

edit- Pool of Radiance at MobyGames

- Pool of Radiance can be played for free in the browser at the Internet Archive

- Dragonbait's Pool of Radiance page, screenshots, info and pics of the original Pool of Radiance (1988)

- Pool of Radiance at Game Banshee - contains a walkthrough and many in-depth specifics about the game.

- Images of Pool of Radiance package, manual and screen for Commodore 64 version

- Pool of Radiance Interactive Code Wheel at oldgames.sk

- Review in Compute!'s Gazette

- Review in Info