This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2017) |

John Henry Tunstall (6 March 1853 – 18 February 1878) was an English-born rancher and merchant in Lincoln County, New Mexico, United States. He competed with the Irish Catholic merchants, lawmen, and politicians who ran the town of Lincoln and the county.[citation needed] Tunstall, a member of the Republican Party, hoped to unseat the Irish and make a fortune as the county's new boss.[citation needed] He was the first man killed in the Lincoln County War, an economic and political conflict that resulted in armed warfare between rival gangs of cowboys and the ranchers, lawmen, and politicians who issued the orders.

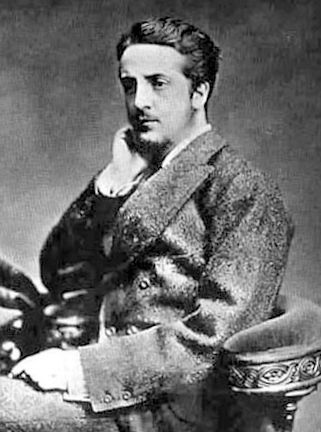

John Tunstall | |

|---|---|

Tunstall in 1875[1] | |

| Born | March 6, 1853 Hackney, London |

| Died | February 18, 1878 (aged 24) |

| Occupation(s) | Rancher and merchant |

| Known for | First man killed in the Lincoln County War |

| Political party | Republican Party |

Early life and education

editTunstall was born in 1853 in Hackney, London. Although Tunstall has often been depicted in fiction as a member of the English nobility, his family were in reality upper middle-class. Furthermore, Tunstall's father "worked in trade", with business interests in both Canada and in the United Kingdom, and would, for this reason, have been looked down on and excluded from polite society. Tunstall lived some of his childhood in Belsize Park.[citation needed]

John Tunstall was always inclined toward agnosticism and, as he entered manhood, "grew increasingly contemptuous of organized religion" and its "ethical restraints."[2]

Emigration and career

editAmbitions

editIn August 1872, Tunstall emigrated to British Columbia, Canada, at age 19, to work as a clerk for Turner, Beeton & Tunstall, a store in which his father owned a partnership.[3]

According to Robert M. Utley, "Three miserable and penurious years of clerking" for his father's partners in Vancouver produced in Tunstall a "firm conviction" that, "the road to riches ... did not lie in the mercantile world."[4]

According to Utley, Tunstall, in his "dreams pictured an empire of sheep or cattle pastured on a great landed estate", where his herds multiplied and his bank account similarly swelled with ever more and more money. In a letter home, Tunstall wrote that although he knew that "a rugged outdoor life" would have its challenges, he predicted, "I shall be far happier than cuffed in white linen & coated in broadcloth, pedalling trifles to women with slim purses & slimmer education & refinement."[5]

With this in mind, Tunstall quit his clerking job in February 1876 and left Canada for California. He spent six months investigating the profits of sheep ranching before he decided instead to shift his inquiries to Santa Fe, the capital of the Territory of New Mexico. There, Tunstall had learned, "a specialized legal profession had grown up around the manipulation of title" to "old Spanish and Mexican land grants."[2]

For more than a year before his arrival, however, Tunstall had "dedicated himself single-mindedly" to persuading his father "of the certainty of a rich harvest, if only he would provide the seeds."[6]

His father, John Partridge Tunstall, was "a shrewd sceptic", who had done very well for his family in the mercantile world and, although he had plenty of capital to invest "did not share his son's explosive enthusiasm for every opportunity that came along."[6]

Santa Fe

editTunstall arrived in the territorial capital of Santa Fe on August 15, 1876, following a weeklong and exhausting journey from San Francisco, first by railroad and then from a painful post atop a horse-drawn "jerky", which kicked dust in his face all the way down the last 220 miles of the Santa Fe Trail. In a letter to his father, Tunstall griped, "I can assure you that one soon discovers why it is called a jerky."[7]

The jerky finally pulled up before Santa Fe's best lodgings, the Exchange Hotel on Santa Fe Plaza, directly opposite from the Palace of the Governors. Prompted, however, by "a dwindling reserve of cash", Tunstall walked to the west on San Francisco Street and instead took lodgings at Herlow's, "a very second class hotel", for a third less the cost. The food at Herlow's, however, fell so far short of Tunstall's expectations that he usually chose to dine at the Exchange.[8]

In Santa Fe, Tunstall met Scottish-Canadian lawyer Alexander McSween, who told him of the potentially big profits to be made in Lincoln County, which was being rapidly settled. McSween was allied with John Chisum, the owner of a large ranch and over 100,000 head of cattle. McSween became a business partner of Tunstall, and they both sought Chisum's support.

The young Englishman bought a ranch on the Rio Feliz, some 30 miles (48 km) nearly due south of the town of Lincoln, and went into business as a cattleman. In the town he also set up a mercantile store and bank down the road from the Murphy & Dolan mercantile and banking operation. It had been established a few years earlier by James Dolan, Lawrence Murphy and John H. Riley, all of whom were Irish immigrants. The Murphy-Dolan store was known colloquially as "The House."

Murphy and Dolan ran the town and surrounding county of Lincoln as though the area were their fiefdom. Any business transaction of consequence in the county passed through them. They controlled the courts. The Sheriff of Lincoln County, William J. Brady, was an Irish immigrant from County Cavan and was allied to the House.

Tunstall was eager to make money in Lincoln County. Offering decent prices and reasonable dealings at his store, he attracted locals eager to find a competitor to Murphy and Dolan. In his letters to his family in London, Tunstall said that he intended to not only unseat Murphy and Dolan, but to become so powerful that half of every dollar made by anyone in Lincoln County would end up in his pocket. He also wrote about how he would soon raise the Tunstalls from the middle class to the highest levels of British polite society.

Death

editTunstall's mercantile business put him into conflict with the powerful political, economic, and judicial structure that ruled New Mexico Territory. This group of men was known as the Santa Fe Ring. Ring members included Thomas Catron, the attorney general and political boss of New Mexico Territory. Catron owned 3,000,000 acres (12,000 km2) of land and was one of the largest land holders in the history of the United States. Among Catron’s colleagues were Samuel Beach Axtell, the Territorial governor, who was fired for corruption by 19th President Rutherford B. Hayes, Warren Henry Bristol, a territorial judge, and William L. Rynerson, a district attorney who had assassinated John P. Slough, the Chief Justice of New Mexico, and escaped punishment for the crime. Catron held the mortgage on "The House” and had a direct interest in its success in Lincoln.

When too many of the residents of Lincoln switched their business to Tunstall's store, Murphy-Dolan began a slide into bankruptcy, and Catron's bottom line was affected. Murphy and Dolan tried to put Tunstall out of business, first harassing him legally, then trying to goad him into a gunfight. They also hired gunmen, most of whom were members of the Jesse Evans Gang, also known as "The Boys."

Tunstall recruited gunfighters of his own, half a dozen local ranchers and cowboys who disliked Brady, Murphy, and Dolan. These men worked Tunstall's ranch and did his bidding during his conflict with Murphy/Dolan. One of Tunstall's employees was the 18-year-old William Bonney (née Henry McCarty, aka William Henry Antrim, aka El Chivato), who was later dubbed "Billy the Kid" when leading a gang of his own.

In the Spring of 1877, Sheriff Brady was beaten up by two bravados, who were believed to be acting on John Tunstall's orders, in the middle of the main street of Lincoln.[9]

On February 18, 1878, Tunstall, Richard M. Brewer, John Middleton, Henry Newton Brown, Robert Widenmann, Fred Waite, and William Bonney were driving nine horses from Tunstall's ranch on the Rio Feliz to Lincoln. A posse deputized by Lincoln Sheriff Brady went to Tunstall's ranch on the Feliz to attach his cattle on a warrant that had been issued against his business partner, McSween. It was a testament to how completely entangled the business affairs of Tunstall and MacSween had become that the posse came to attach Tunstall's cattle as collateral for MacSween's debts.

Finding Tunstall, his hands, and the horses gone, a sub-posse broke from the main posse and went in pursuit. However, these horses were not covered by any legal action.

Deputies Jesse Evans, Henry Hill, Morton (and probably Frank Baker) rode ahead after Tunstall. Evans, Morton, and Hill caught up with Tunstall and his men in an area covered with scrub timber a few miles from Lincoln. Tunstall, the nine horses, and his hired guns were spread out along the narrow trail. Bonney, who was riding drag, alerted the others. The deputies began firing without warning. Tunstall's hands galloped off through the brush to a hilltop overlooking the trail. Tunstall first stayed with his horses, then rode away but was pursued by the three deputies.

Only the three deputies survived the following confrontation. The historian Robert Utley writes that Tunstall may have surrendered or he may just as easily have drawn his sidearm and tried to defend himself from Deputies Morton, Hill, and Evans. Either way, the shooting began and Tunstall died instantly when hit by two rifle bullets, one in the chest and another that ripped through his brain. In the aftermath, Tunstall's supporters "claimed that he was murdered in cold blood". Supporters of the House, however, "insisted that he had been shot down while resisting arrest by a lawfully commissioned deputy sheriff of Lincoln County." Tunstall was 24 years old.[10]

Aftermath

editTunstall's murder ignited the Lincoln County War.

In response, William Bonney, Richard M. Brewer, Chavez y Chavez, Doc Scurlock, Charlie Bowdre, George Coe, Frank Coe, Jim French, Frank McNab and other employees and friends of Tunstall's went to the Lincoln County Justice of the Peace, "Squire" John Wilson. He proved sympathetic to their cause and swore them all in as special constables to bring in Tunstall's killers. This posse was legal and led by Richard "Dick" Brewer, a respected local rancher who had worked as Tunstall's foreman. The newly minted lawmen dubbed themselves The Regulators and went first in search of Deputies Evans, Morton, Hill, and Baker and all the others implicated in Tunstall's death. Thus, two groups of lawmen rode throughout Lincoln County at war with each other.

The Regulators tracked down and arrested Deputies Morton and Baker on March 6. In what may or may not have been a calculated revenge killing, both Deputies were killed soon after, officially while attempting to escape. After returning to Lincoln, the Regulators further claimed that Deputies Norton and Baker had also killed McCloskey of the Regulators. Meanwhile, Lincoln County Deputies Jesse Evans and Tom Hill were rustling sheep during which Hill was killed and Evans was wounded by the sheep farmer. Several other revenge killings, committed by both the Regulators and the gunmen hired by Murphy-Dolan, soon followed.

On April 1, 1878, the Regulators ambushed and fatally shot Lincoln County Sheriff William Brady and Deputy George Hindemann. Half a dozen Regulators, including Bonney, Jim French, and Frank McNab carried out the revenge killings. The Regulators killed Buckshot Roberts at Blazer's Mills, southwest of Lincoln in area now within the Mescalero Apache Reservation. Their man Richard Brewer also died in this shootout.

The period of July 15 through July 19, 1878, Battle of Lincoln became known as "The Five-Day Battle." The U.S. Army from nearby Fort Stanton, under the command of Colonel Nathan Dudley, intervened in the fight and defeated the Regulators. Dudley threatened the Regulators while the Dolanites strutted along Lincoln's street. A new federal law of 1878, passed by a Democratic majority of Congress and in reaction to the former use of military forces in southern states to suppress violence targeting freedmen during the Reconstruction era, prohibited the Army from intervening in civilian conflicts.

After their loss to the Dolan forces in the Five-Day Battle, the Regulators and their supporters quickly left town. Bonney remained in New Mexico, moving to Fort Sumner, New Mexico, 160 miles west of the Texas Panhandle on the Pecos River. Bonney operated as a bandit in the area with his own gang and survived until July 14, 1881, when he was shot and killed at Fort Sumner by Sheriff Pat Garrett of Lincoln County. Garrett had been given a mandate[by whom?] to get rid of Billy the Kid and his gang.

Legacy

editJohn Tunstall had lived in Lincoln for about 18 months before being killed by Deputies Morton, Hill, and Evans. During this period, he regularly corresponded with his family in London. Frederick Nolan collected these letters and published them as The Life and Death of John Henry Tunstall, a basic work in the historiography of the Lincoln County War. Tunstall's letters reflect his ambition, biases, and youthful arrogance and high-spiritedness. They also reflect the economic, cultural, social, and political realities of the time and place. Tunstall's gun is held by the Royal Armouries Museum in Leeds, UK.

References

editCitations

edit- ^ "John Henry Tunstall". Find a Grave.

- ^ a b Utley 1989, p. 17.

- ^ Nolan 2009, p. 21.

- ^ Utley 1989, p. 4.

- ^ Utley 1989, p. 16.

- ^ a b Utley 1989, p. 15.

- ^ Utley 1989, p. 13.

- ^ Utley 1989, p. 14.

- ^ Larry D. Ball (1992), Desert Lawmen: the high sheriffs of New Mexico and Arizona, 1846–1912. Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press, Page 200.

- ^ Utley 1989, p. 12.

Sources

edit- Dickson, Brandon (October 2023). "The Posse That Killed John Tunstall: The story of what happened to them". The Tombstone Epitaph. CXXXXXIII (10). Tombstone, AZ: 1, 8–9, 13. ISSN 1940-221X.

- Fulton, Maurice Garland. History of the Lincoln County War. Edited by Robert Mullin. Phoenix: University of Arizona Press, 1968. [ISBN missing]

- Jacobsen, Joel (1994). Such Men As Billy The Kid. The Lincoln County War Reconsidered. Lincoln, NE and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803225763.

- Garrett, Pat F. The Authentic Life of Billy, the Kid. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1954. [ISBN missing]

- Hunt, Frazier. The Tragic Days of Billy The Kid. New York: Hastings House, 1956. [ISBN missing]

- Nolan, Frederick. The Life and Death of John Henry Tunstall. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1965. [ISBN missing]

- Nolan, Frederick W. (2009). The Lincoln County War: A Documentary History. Sunstone Press. ISBN 978-0-86534-721-2.

- Nolan, Frederick. The West of Billy The Kid. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1998. [ISBN missing]

- Utley, Robert M. (1989). High Noon in Lincoln: Violence on the Western Frontier. UNM Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-2546-4.

- Wilson, John P. Merchants, Guns and Money: The Story of Lincoln County and Its Wars. Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press, 1987. [ISBN missing]