Battle of Rovereto

| Battle of Rovereto | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Italian campaigns in the War of the First Coalition | |||||||

Battle of Rovereto | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 20,000[1] | 20,000[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 750[1] | 6,000 killed or wounded, 4,000 prisoners, 25 guns, 7 colours[1] | ||||||

Location within Northern Italy | |||||||

In the Battle of Rovereto (also Battle of Roveredo) on 4 September 1796 a French army commanded by Napoleon Bonaparte defeated an Austrian corps led by Paul Davidovich during the War of the First Coalition, part of the French Revolutionary Wars. The battle was fought near the town of Rovereto, in the upper Adige River valley in northern Italy.

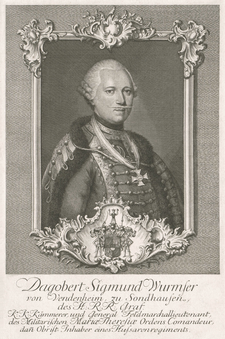

The action was fought during the second relief of the siege of Mantua. The Austrians left Davidovich's corps in the upper Adige valley while transferring two divisions to Bassano del Grappa by marching east, then south down the Brenta River valley. The Austrian army commander Dagobert von Würmser planned to march south-west from Bassano to Mantua, completing the clockwise manoeuvre. Meanwhile, Davidovich would threaten a descent from the north to distract the French.

Bonaparte's next move did not conform to the Austrians' expectations. The French commander advanced north with three divisions, a force that greatly outnumbered Davidovich. The French steadily pressed back the Austrian defenders all day and routed them in the afternoon. Davidovich retreated well to the north. This success allowed Bonaparte to follow Würmser down the Brenta valley to Bassano and, ultimately, trap him inside the walls of Mantua.

Background

[edit]Plans

[edit]After being defeated in the Battle of Castiglione on 5 August, the Austrian army under Feldmarschall Würmser retreated north to Trento. Meanwhile, the French army resumed the siege of Mantua. Pre-dawn attacks on 24 August led by General of Division Jean-Joseph Sahuguet and General of Brigade Claude Dallemagne pressed the Austrian garrison back into the fortress.[2]

On 26 August orders arrived from Emperor Francis II to immediately attempt a second relief of the fortress of Mantua. Würmser's new chief-of-staff, Feldmarschall-Leutnant Franz von Lauer therefore drew up plans for an offensive. The division of Feldmarschall-Leutnant Johann Mészáros near Bassano was reinforced to 10,700 troops. Würmser would lead two divisions from Trento into the Brenta River valley. This route went east, then south to reach Bassano. From that location, the Austrians would turn southwest, join Mészáros, and march to Mantua via Legnago.[3]

The 17,300-man Mantua garrison was sent orders to stage attacks on the besiegers when the relief army drew close. Feldmarschall-Leutnant Davidovich with 19,600 troops defended Trento.[4] If the French forces facing him weakened, he was to move south on Mantua. Lauer noted that the French army, "had suffered badly during the recent combats, and had not properly recovered, nor received significant reinforcements. However, he drew some dangerous conclusions from this..." Lauer confidently predicted that the French army would remain quiet long enough for the Austrian relief effort to get well underway.[5]

In fact, the French government approved a strategy that sent the Army of Italy north across the Brenner Pass to link with General of Division Jean Moreau's army in Bavaria. Accordingly, General of Division Bonaparte planned to mass 33,000 soldiers from the divisions of Generals of Division Claude Belgrand de Vaubois, André Masséna, and Pierre Augereau, then advance to Trento. His remaining 13,500 men covered the blockade of Mantua and the line of the Adige near Verona and Legnago.[6] Bonaparte instructed Sahuguet and General of Division Charles Kilmaine to leave a garrison in Peschiera del Garda and fall back behind the Oglio River if they were unable to resist an Austrian attack from the east.[7]

Battle

[edit]

The 4,100-man division Feldmarschall-Leutnant Karl Philipp Sebottendorf moved out on 1 September. It was soon followed by Feldmarschall-Leutnant Peter Quasdanovich's 4,600 soldiers. Davidovich controlled 19,555 troops, but only 13,695 of these were immediately available. He deployed the brigades of General-majors Josef Philipp Vukassovich and Johann Rudolf von Sporck near Rovereto, while the brigade of General-major Prince Heinrich XV of Reuss-Plauen held Trento and some positions west of the Adige. The brigades of General-major Johann Loudon in the Valtelline and General-major Johann Grafen in the Vorarlberg were not within supporting distance.[4]

Vaubois, with 10,000 men, lay to the west of Lake Garda. He put General of Brigade Jean Joseph Guieu and his brigade in boats, while his other two brigades marched north past Lake Idro to Riva del Garda at the northern end of the lake. Joined by Guieu, Vaubois turned east toward Rovereto. Bonaparte sent Masséna's 13,000 troops advancing directly north up the Adige valley while Augereau's 9,000 men struggled through the mountains north of Verona.[8]

On 3 September, Masséna attacked 1,500 of Vukassovich's troops near Ala and drove them back to Marco on the east bank of the Adige. Vukassovich tried to warn Davidovich, but his superior was away at a conference with Würmser in Trento. Vaubois brushed aside some elements of Reuss's brigade at Nago-Torbole and stood poised to attack an Austrian position at Mori on the west bank. Meanwhile, Würmser became aware of the French threat to Trento, but he nevertheless pursued his strategy of moving via the Brenta valley.[9]

At dawn, Masséna's division attacked Vukassovich's Austrians at Marco. General of Brigade Claude Perrin Victor led one demi-brigade straight up the main road, while General of Brigade Jean Joseph Magdeleine Pijon seized the high ground to one flank. After sturdy resistance, the Austrians pulled back to avoid being cut off. Masséna pursued vigorously, breaking up a number of Austrian formations. When he reached Rovereto, Vukassovich stood firm again until noon-time. Then he fell back toward Calliano with the remnant of his brigade and Sporck's troops. By this time, Vaubois had captured Mori on the west bank.[10]

Davidovich placed Colonel Karl Weidenfeld and the Preiss Infantry Regiment 24 in a formidable position in the Adige gorge to cover the retreat of his forces. However, the regiment's morale was poor after suffering casualties and being hustled out of several defensive lines. Aided by artillery fire directed by General of Brigade Elzéar Auguste Cousin de Dommartin, Masséna's troops attacked in heavy columns and broke through. Believing themselves well-covered by Weidenfeld's force, Vukassovich and Sporck allowed their troops to cook dinner when they arrived in Calliano. Without warning, the French interrupted the proceedings by storming into the camp in the late afternoon. The result was a rout of the surviving Austrians.[11]

Result

[edit]The French lost 750 casualties during the day. Austrian losses between from 3,000 and 10,000 killed, wounded, and prisoners, plus 25 cannon and 7 colours captured.[12][13] During the night, Davidovich evacuated Trento and fell back to Lavis, a village at the river Avisio and southern frontier of Austrian territory, where he joined Reuss. Masséna entered Trento on the morning of 5 September, followed by Vaubois. At this time, Bonaparte found out Würmser's plan of marching east into the Brenta valley. He discarded the strategy of joining Moreau and adopted a very bold plan.[14]

Far from retiring down the Adige with his whole army, Bonaparte ordered Vaubois to block the gorges north of Trent with 10,000 men, while the remaining 22,000 troops set off in full pursuit of Würmser down the same pass that the Austrians were using. This was an extremely risky course to pursue, for during the operation the Army of Italy would be wholly dependent on what supplies it could seize locally, and even a temporary check on the Brenta might lead to starvation in the midst of the Alps."[15]

On 5 September, Vaubois crossed the bridge of the river Avisio, attacked Davidovich at Lavis and drove him farther north. Satisfied that Davidovich was no longer a threat, Bonaparte sent Augereau's division to Levico Terme on the trail of Würmser. Soon, Masséna's troops followed in Augereau's wake.[16] This set the stage for the subsequent skirmish at Primolano on 7 September and the Battle of Bassano on 8 September.[17]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b c d Histoire militaire de la France, p.100.

- ^ Boycott-Brown, p. 415.

- ^ Boycott-Brown, pp. 415–416.

- ^ a b Boycott-Brown, p. 418–419.

- ^ Boycott-Brown, p. 416.

- ^ Boycott-Brown, p. 419.

- ^ Fiebeger, p. 12.

- ^ Boycott-Brown, p. 421–423.

- ^ Boycott-Brown, p. 422–423.

- ^ Boycott-Brown, p. 424–425.

- ^ Boycott-Brown, p. 425–426.

- ^ Smith122

- ^ Histoire militaire de la France, page 100.

- ^ Boycott-Brown, p. 427–428.

- ^ Chandler, p. 97.

- ^ Boycott-Brown, p. 428–429.

- ^ Smith, p. 123.

References

[edit]- Boycott-Brown, Martin. The Road to Rivoli. London: Cassell & Co., 2001. ISBN 0-304-35305-1

- Chandler, David. The Campaigns of Napoleon. New York: Macmillan, 1966.

- Fiebeger, G.J. (1911). The Campaigns of Napoleon Bonaparte of 1796–1797. West Point, New York: US Military Academy Printing Office.

- Smith, Digby. The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill, 1998. ISBN 1-85367-276-9

- Napoleone Bonaparte, Memorie della campagna d'Italia, Roma, Donzelli editore, 2012, ISBN 978-88-6036-714-3.

Sources

[edit]- Guerres des Français en Italie, 1794–1814, 1859.

- Histoire militaire de la France de Pierre Giguet, 1849.

External links

[edit]Media related to Battle of Rovereto at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Battle of Würzburg |

French Revolution: Revolutionary campaigns Battle of Rovereto |

Succeeded by Battle of Bassano |