Robert Oppenheimer

Appearance

Julius Robert Oppenheimer (22 April 1904 – 18 February 1967) was an American physicist and the scientific director of the Manhattan Project.

Quotes

[edit]

It was evening when we came to the river

With a low moon over the desert

that we had lost in the mountains, forgotten,

what with the cold and the sweating

and the ranges barring the sky.

And when we found it again,

In the dry hills down by the river,

half withered, we had

the hot winds against us.There were two palms by the landing;

The yuccas were flowering; there was

a light on the far shore, and tamarisks.

We waited a long time, in silence.

Then we heard the oars creaking

and afterwards, I remember,

the boatman called us.

We did not look back at the mountains.- "Crossing" describing memories of New Mexico in Hound and Horn (June 1928)

- I can't think that it would be terrible of me to say — and it is occasionally true — that I need physics more than friends.

- Letter to his brother Frank Oppenheimer (14 October 1929), published in Robert Oppenheimer : Letters and Recollections (1995) edited by Alice Kimball Smith, p. 135

- Everyone wants rather to be pleasing to women and that desire is not altogether, though it is very largely, a manifestation of vanity. But one cannot aim to be pleasing to women any more than one can aim to have taste, or beauty of expression, or happiness; for these things are not specific aims which one may learn to attain; they are descriptions of the adequacy of one's living. To try to be happy is to try to build a machine with no other specification than that it shall run noiselessly.

- Letter to his brother Frank (14 October 1929), published in Robert Oppenheimer : Letters and Recollections (1995) edited by Alice Kimball Smith, p. 136

- I believe that through discipline, though not through discipline alone, we can achieve serenity, and a certain small but precious measure of the freedom from the accidents of incarnation, and charity, and that detachment which preserves the world which it renounces. I believe that through discipline we can learn to preserve what is essential to our happiness in more and more adverse circumstances, and to abandon with simplicity what would else have seemed to us indispensable; that we come a little to see the world without the gross distortion of personal desire, and in seeing it so, accept more easily our earthly privation and its earthly horror — But because I believe that the reward of discipline is greater than its immediate objective, I would not have you think that discipline without objective is possible: in its nature discipline involves the subjection of the soul to some perhaps minor end; and that end must be real, if the discipline is not to be factitious. Therefore I think that all things which evoke discipline: study, and our duties to men and to the commonwealth, war, and personal hardship, and even the need for subsistence, ought to be greeted by us with profound gratitude, for only through them can we attain to the least detachment; and only so can we know peace.

- Letter to his brother Frank (12 March 1932), published in Robert Oppenheimer : Letters and Recollections (1995) edited by Alice Kimball Smith, p. 155

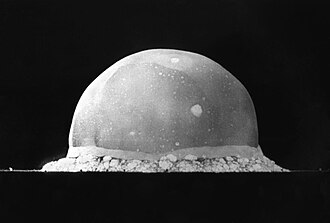

- It worked!

- His exclamation after the Trinity atomic bomb test (16 July 1945), according to his brother in the documentary The Day After Trinity

- It is with appreciation and gratefulness that I accept from you this scroll for the Los Alamos Laboratory, and for the men and women whose work and whose hearts have made it. It is our hope that in years to come we may look at the scroll and all that it signifies, with pride. Today that pride must be tempered by a profound concern. If atomic bombs are to be added as new weapons to the arsenals of a warring world, or to the arsenals of the nations preparing for war, then the time will come when mankind will curse the names of Los Alamos and Hiroshima. The people of this world must unite or they will perish. This war that has ravaged so much of the earth, has written these words. The atomic bomb has spelled them out for all men to understand. Other men have spoken them in other times, and of other wars, of other weapons. They have not prevailed. There are some misled by a false sense of human history, who hold that they will not prevail today. It is not for us to believe that. By our minds we are committed, committed to a world united, before the common peril, in law and in humanity.

- Acceptance Speech, Army-Navy "Excellence" Award (16 November 1945)

- Despite the vision and farseeing wisdom of our wartime heads of state, the physicists have felt the peculiarly intimate responsibility for suggesting, for supporting, and in the end, in large measure, for achieving the realization of atomic weapons. Nor can we forget that these weapons, as they were in fact used, dramatized so mercilessly the inhumanity and evil of modern war. In some sort of crude sense which no vulgarity, no humor, no overstatement can quite extinguish, the physicists have known sin; and this is a knowledge which they cannot lose.

- Physics in the Contemporary World, Arthur D. Little Memorial Lecture at M.I.T. (25 November 1947)

- The extreme danger to mankind inherent in the proposal [to develop thermonuclear weapons] wholly outweighs any military advantage.

- Robert Oppenheimer et al., Report of the General Advisory Committee, 1949

- There must be no barriers to freedom of inquiry … There is no place for dogma in science. The scientist is free, and must be free to ask any question, to doubt any assertion, to seek for any evidence, to correct any errors. Our political life is also predicated on openness. We know that the only way to avoid error is to detect it and that the only way to detect it is to be free to inquire. And we know that as long as men are free to ask what they must, free to say what they think, free to think what they will, freedom can never be lost, and science can never regress.

- As quoted in "J. Robert Oppenheimer" by L. Barnett, in Life, Vol. 7, No. 9, International Edition (24 October 1949), p. 58; sometimes a partial version (the final sentence) is misattributed to Marcel Proust.

- Our own political life is predicated on openness. We do not believe any group of men adequate enough or wise enough to operate without scrutiny or without criticism. We know that the only way to avoid error is to detect it, that the only way to detect it is to be free to enquire. We know that the wages of secrecy are corruption. We know that in secrecy error, undetected, will flourish and subvert.

- "Encouragement of Science", an address at Science Talent Institute (6 March 1950), Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Vol. 7, #1 (Jan 1951) p. 6-8

- We may be likened to two scorpions in a bottle, each capable of killing the other, but only at the risk of his own life.

- "Atomic Weapons and American Policy", Foreign Affairs (July 1953), p. 529

- The open society, the unrestricted access to knowledge, the unplanned and uninhibited association of men for its furtherance — these are what may make a vast, complex, ever growing, ever changing, ever more specialized and expert technological world, nevertheless a world of human community.

- Science and the Common Understanding (1953)

- The history of science is rich in the example of the fruitfulness of bringing two sets of techniques, two sets of ideas, developed in separate contexts for the pursuit of new truth, into touch with one another.

- Science and the Common Understanding (1954); based on 1953 Reith lectures.

- There are no secrets about the world of nature. There are secrets about the thoughts and intentions of men.

- Interview with Edward R. Murrow, A Conversation with J. Robert Oppenheimer (1955)

- Much has been said of the prospect that man, along with many other forms of life...would disappear as a species. In time, not a long time, that may come to be possible. What is more certain and more immediate is that we would lose much of our human inheritance, much that has made our civilization and our humanity...the threat of the apocalypse will be with us for a long time; the apocalypse may come.

- Science and our Times, 1956

- It's not that I don't feel bad about it. It's just that I don't feel worse today than what I felt yesterday.

- Response to question on his feelings about the atomic bombings, while visiting Japan in 1960.

- We waited until the blast had passed, walked out of the shelter and then it was extremely solemn. We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried. Most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad-Gita: Vishnu is trying to persuade the Prince that he should do his duty and, to impress him, he takes on his multi-armed form and says, "Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds." I suppose we all thought that, one way or another.

- Interview about the Trinity explosion, first broadcast as part of the television documentary The Decision to Drop the Bomb (1965), produced by Fred Freed, NBC White Paper; the translation is his own. Online video is at atomicarchive.com

- The "Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds" line, spoken to the prince Arjuna by Krishna (not Vishnu, although Krishna is an avatar of Vishnu), is usually translated differently. Oppenheimer's Sanskrit teacher, Arthur Ryder, translated it as "Death am I, and my present task. / Destruction." Most translations tend to translate it as "time" or "terrible time." Either way, the point is the same: Arjuna is reluctant to go to war, and Krishna has been exhorting him to fulfill his duties as a prince despite his misgivings. Ultimately, Krishna is saying, Arjuna is just an instrument of death acting on his behalf, unable to stop the fate of death that comes to all eventually. Arjuna, suitably humbled, agrees to engage in battle. See discussion at Alex Wellerstein, "Oppenheimer and the Gita," _Restricted Data: The Nuclear Secrecy Blog_ (23 May 2014), drawing upon the research of James A. Hijiya, "The Gita of J. Robert Oppenheimer," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 144, no. 2 (June 2000), 123-167. Hijiya argues that contrary to most common interpretations of Oppenheimer's quote, it is not about Oppenheimer claiming to be "death, the destroyer of worlds" himself, but is an analogy about responsibility and duty.

- However, it is my judgment in these things that when you see something that is technically sweet, you go ahead and do it and you argue about what to do about it only after you have had your technical success. That is the way it was with the atomic bomb. I do not think anybody opposed making it; there were some debates about what to do with it after it was made. I cannot very well imagine if we had known in late 1949 what we got to know by early 1951 that the tone of our report would have been the same.

- Oppenheimer testifying in his defense in his 1954 security hearings, discussing the American reaction to the first successful Russian test of an atomic bomb and the debate whether to develop the "super" hydrogen bombs with vastly higher explosive power; from volume II of the Oppenheimer hearing transcripts, pg266. Date: Tuesday, April 13.

- I think it is the opposite of true. Let us not say about use. But my feeling about development became quite different when the practicabilities became clear. When I saw how to do it, it was clear to me that one had to at least make the thing. Then the only problem was what would one do about them when one had them. The program we had in 1949 was a tortured thing that you could well argue did not make a great deal of technical sense. It was therefore possible to argue also that you did not want it even if you could have it. The program in 1951 was technically so sweet that you could not argue about that. It was purely the military, the political and the humane problem of what you were going to do about it once you had it...

- Oppenheimer testifying in his defense in his 1954 security hearings. Date: Friday, April 16.

- But when you come right down to it the reason that we did this job is because it was an organic necessity. If you are a scientist you cannot stop such a thing. If you are a scientist you believe that it is good to find out how the world works; that it is good to find out what the realities are; that it is good to turn over to mankind at large the greatest possible power to control the world and to deal with it according to its lights and its values.

- His early papers are paralyzingly beautiful but they are thoroughly corrupt with errors, and this has delayed the publication of his collected works for almost ten years. Any man whose errors can take that long to correct is quite a man.

- Memorial lecture delivered on 13 December 1965 at UNESCO headquarters to commemorate the tenth anniversary of Albert Einstein's death, as quoted in Silvan S. Schweber, Einstein and Oppenheimer: The Meaning of Genius (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008), pp. 279-280.

- Science is not everything, but science is very beautiful.

- Last published words With Oppenheimer on an Autumn Day, Look, Vol. 30, No. 26 (19 December 1966)

- It is a profound and necessary truth that the deep things in science are not found because they are useful; they are found because it was possible to find them.

- Because I was an idiot.

- Oppenheimer's explanation for why he lied to security officers on the Manhattan Project about the so-called Chevalier Affair, in which he claimed to have been approached to assist with Soviet atomic espionage during World War II. Testimony of J. Robert Oppenheimer in U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, _In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer_ (GPO, 1954), on 137.

- I can make it clearer; I can't make it simpler.

- Words spoken to his class at Berkeley during the period 1932-1934, as quoted by Wendell Furry in American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer (2005), by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, p. 84

- The Bhagavad Gita is the most beautiful philosophical song existing in any known tongue.

- Attributed. in Glimpses of India Jaideva C. Goswami, and Royal, Denise The Story of J Robert Oppenheimer St. Martin's Press New York 1969p. 54 x

- The general notions about human understanding ... which are illustrated by discoveries in atomic physics are not in the nature of things wholly unfamiliar, wholly unheard of, or new. Even in our own culture, they have a history, and in Buddhist and Hindu thought a more considerable and central place. What we shall find is an exemplification, an encouragement, and a refinement of old wisdom.

- Attributed. Pt. Deendayal Upadhyay Ideology & Preception - Part - 1: An Inquest, D B Tengadi and in Capra, Fritjof The Tao of physics: an exploration of the parallels between modern physics and eastern mysticism New York: Bantam Books, 1977.p. 18, and in The Systems View of Life: A Unifying Vision

- Access to the Vedas is the greatest privilege this century may claim over all previous centuries.

- Attributed. as quoted in Londhe, S. (2008). A tribute to Hinduism: Thoughts and wisdom spanning continents and time about India and her culture and in History of Ancient India Revisited, A Vedic-Puranic View, Omesh K. Chopra, page 399 and in Glimpses of India Jaideva C. Goswami

Misattributed

[edit]- The Optimist thinks this is the best of all possible worlds, the Pessimist fears it is true.

- This is derived from a statement of James Branch Cabell, in The Silver Stallion (1926) : The optimist proclaims that we live in the best of all possible worlds; and the pessimist fears this is true.

Quotes about Oppenheimer

[edit]

- Sorted alphabetically by author or source

- J. Robert Oppenheimer had graduated from Fieldston (the branch on Central Park West, then named the Ethical Culture School) in 1921, and while Minsky was there the memory of Oppenheimer’s student days was still fresh. “If you did anything astonishing at Fieldston, some teacher would say, ‘Oh, you’re another Oppenheimer,’ ” Minsky recalled. “At the time, I had no idea what that meant.”

- Marvin Minsky, quoted in Bernstein, Jeremy (1981-12-06). "Marvin Minsky’s Vision of the Future" (in en-US). The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X.

- Oppenheimer thought that no one could be expected to learn quantum mechanics from books alone; the verbal wrestling inherent in the process of explanation is what opens the door to understanding.

- Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin in: American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. 18 December 2007. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-307-42473-0.

- He was the genius of the nuclear weapons age and also the walking, talking conscience of science and civilisation; most of the great questions surrounding him as a person were the greatest questions of that time.

He was born into an intellectual New York Jewish family and as a young man experienced the revolution in theoretical physics in the 1920s at first hand in Europe, before settling in California and building a world-class research centre there. Though he had no record as a manager, when war came he was chosen as the Manhattan Project's chief scientist and his inspirational leadership saw it through to success.

Peace found him a national hero and a powerful voice in Washington, but he was also increasingly anxious about the drift into Cold War. These qualms made him enemies, so his pre-war left-wing past was dredged up and, at those 1954 hearings, he was subjected to what one observer called a "dry crucifixion". … Not a shred of credible evidence was ever produced to suggest that the man was disloyal, still less that he was a spy. The worst that could be proved against him was one or two lapses of judgement in dealings with left-wing friends in the early years of the war — piffling faults, as Isidor Rabi pointed out, when set beside his achievements.

So demented were his enemies that, even after what they described as his "unfrocking" — the official decision that he did indeed pose a risk to national security — they insisted he was on the brink of defecting to the Soviet Union and so must continue to be followed and bugged wherever he went.

- The custom for these colloquia was that Oppenheimer, a very punctual guy, would walk out on stage from one of the wings, make a few general remarks in his own quiet way, and then introduce the speaker. Not this time. He arrived very late and entered the theater from the rear, strode down the aisle while all of us rose and cheered him, stomped our feet and in general behaved like a pack of bloodthirsty savages welcoming back their conquering warriors, who were displaying the heads or genitals, or both, of the conquered.

When Oppenheimer was able to finally quiet down the mob, he set about telling us what little was known about the results of the bombing. There was one thing he knew for sure: the “Japs” (not Japanese) didn’t like it. More howling, foot stomping, and the like. Then he got to the nub of the matter: While we apparently had been successful, and his chest was practically bursting with pride, he did have one deep regret, that we hadn’t completed the Bomb in time to use against the Germans. That really brought down the house.

This had to be the most fascinating, to say nothing about being the most historic, speech I’ve ever heard. Apart from those who were there that night, I don’t recall ever meeting anyone who had ever heard of it. There’s an explanation for this that I won’t bother to go into here because that’s not what I’m writing about. That’s a matter for a good investigative reporter with an historic bent to go into, and maybe get himself a Pulitzer award.- Samuel T. Cohen, on statements made by Oppenheimer, just after the bombing of Hiroshima, in F*** You! Mr. President: Confessions of the Father of the Neutron Bomb (2006)

- His theoretical prediction of black holes was by far his greatest scientific achievement, fundamental to the modern development of relativistic astrophysics, and yet he never showed the slightest interest in following it up. So far as I can tell, he never wanted to know whether black holes actually existed. ...We know that the Oppenheimer-Snyder calculation is correct and describes what happens to massive stars at the end of their lives. It explains why black holes are abundant, and incidentally confirms the truth of Einstein's theory of general relativity. And still, Robert Oppenheimer was not interested. ...How could he have remained blind to his greatest discovery? ...Perhaps if the Oppenheimer-Snyder calculation had not happened to coincide with the Bohr-Wheeler theory of nuclear fission and with the outbreak of World War II, Robert would have paid more attention to it.

- Freeman Dyson, The Scientist As Rebel (2006)

- In later years I found a key to the character of Robert by comparing him with Lawrence of Arabia. Lawrence was in many ways like Robert, a scholar who came to greatness through war, a charismatic leader, and a gifted writer, who failed to readjust happily to peacetime existence after the war, and was accused with some justice of occasional untruthfulness.

- Freeman Dyson, The Scientist As Rebel (2006)

- His flaw was restlessness, an inborn inability to be idle. Intervals of idleness are probably essential to creative work on the highest level. Shakespeare, we are told was habitually idle between plays.

- Freeman Dyson, The Scientist As Rebel (2006)

- Robert was well aware of his own weakness. In later life he never spoke of himself directly, but he occasionally expressed his inner thoughts obliquely by quoting poetry. Especially from George Herbert, his favorite poet.

- Freeman Dyson, The Scientist As Rebel (2006)

- The trouble with Oppenheimer is that he loves a woman who doesn't love him — the United States government. ... [T]he problem was simple: All Oppenheimer needed to do was go to Washington, tell the officials that they were fools, and then go home.

- Albert Einstein, to Abraham Pais, as quoted in Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin in: American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 504. ISBN 978-0-307-42473-0.. Einstein felt that Oppenheimer was a _narr_ (fool) for going through with his security hearing.

- One of the first interesting experiences I had in this project at Princeton was meeting great men. I had never met very many great men before. But there was an evaluation committee that had to try to help us along, and help us ultimately decide which way we were going to separate the uranium. This committee had men like Compton and Tolman and Smyth and Urey and Rabi and Oppenheimer on it. I would sit in because I understood the theory of how our process of separating isotopes worked, and so they'd ask me questions and talk about it. In these discussions one man would make a point. Then Compton, for example, would explain a different point of view. He would say it should be this way, and he was perfectly right. Another guy would say, well, maybe, but there's this other possibility we have to consider against it. So everybody is disagreeing, all around the table. I am surprised and disturbed that Compton doesn't repeat and emphasize his point. Finally at the end, Tolman, who's the chairman, would say, "Well, having heard all these arguments, I guess it's true that Compton's argument is the best of all, and now we have to go ahead." It was such a shock to me to see that a committee of men could present a whole lot of ideas, each one thinking of a new facet, while remembering what the other fella said, so that, at the end, the decision is made as to which idea was the best -- summing it all up -- without having to say it three times. These were very great men indeed.

- Richard Feynman, from the First Annual Santa Barbara Lectures on Science and Society, University of California at Santa Barbara (1975)

- We made a film about the man who created the atomic bomb, and for better or for worse, we’re all living in Oppenheimer’s world. So I would really like to dedicate this to the peacemakers everywhere.

- ...The suspension of the clearance of Dr. Oppenheimer was a very unfortunate thing and should not have been done. In other words, there he was; he is a consultant, and if you don't want to consult the guy, you don't consult him, period. Why you have to then proceed to suspend clearance and go through all this sort of thing, he is only there when called, and that is all there was to it So it didn't seem to me the sort of thing that called for this kind of proceeding at all against a man who had accomplished what Dr. Oppenheimer has accomplished. There is a real positive record, the way I expressed it to a friend of mine. We have an A-bomb and a whole series of it, and we have a whole series of Super bombs, and what more do you want, mermaids? This is just a tremendous achievement. If the end of that road is this kind of hearing, which can't help but be humiliating, I thought it was a pretty bad show. I still think so.

- Isidor Isaac Rabi, testifying during Oppenheimer's 1954 security hearing on why he felt the hearing was an unnecessary and inappropriate activity given the accomplishments of Oppenheimer. Testimony of I.I. Rabi in U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, _In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer_ (GPO, 1954), on 468. The line "and we have a whole series of Super bombs" was censored in the public version and only released in 2015.

- Oppenheimer did not doubt that he would be remembered to some degree, and reviled, as the man who led the work of bringing to mankind for the first time in its history the means of its own destruction.

- Richard Rhodes: The Making of the Atomic Bomb

- some poems that are in The Halfbreed Chronicles are addressed to people like Robert Oppenheimer. Nobody would ever look at him in a racial sense as a half-breed person, yet at the same time he was in a context and at a time, and made choices in his life, that for me apply the metaphor of half-breed to him.

- Wendy Rose interview in Winged Words: American Indian Writers Speak by Laura Coltelli (1990)

- it is impossible to form a sound judgment of Dr. Oppenheimer's situation without acquaintance with at least what the transcript tells us of the highly complicated context in which these charges were raised and explored...It is my guess that everyone around Dr. Oppenheimer has been much educated by Dr. Oppenheimer's experience. But so has Dr. Oppenheimer himself been educated, and not only by the experience of his own investigation but by his total political experience of recent years. There was a time, before Dr. Oppenheimer had come to understand the true nature of the Soviet Union, when surely it was the gravest of risks to trust him with secrets which the Soviet Union wanted so badly. But he never told those secrets then, and to have granted him clearance at that time only to take it away from him now, when at last he has learned the error of his way, seems to me at best to be tragic ineptitude. In effect, it constitutes a projection upon Dr. Oppenheimer of the punishment we perhaps owe to ourselves for having once been so careless with our nation's security.

- Diana Trilling 1954 essay in Claremont Essays (1965)

External links

[edit]- Oppenheimer : A Life online exhibit

- Voices of the Manhattan Project : Audio Interview with J. Robert Oppenheimer by Stephane Groueff (1965)

- PBS American Experience / The Trials of J. Robert Oppenheimer

- "Freedom and Necessity in the Sciences" audio and documents from a lecture at Dartmouth College (14 April 1959)

- Biographical Memoirs: Robert Oppenheimer by Hans Bethe

- Trinity test summary in The Manhattan Project at DOE

- Robert Oppenheimer on IMDb · Oppenheimer (character) at IMDb

Categories:

- 1904 births

- 1967 deaths

- Academics from the United States

- Physicists from the United States

- Engineers from the United States

- Jews from the United States

- Agnostics from the United States

- Anti-fascists

- People from New York City

- Harvard University alumni

- University of Cambridge alumni

- University of California, Berkeley faculty

- Members of the American Philosophical Society

- California Institute of Technology faculty

- People of World War II

- People of the Cold War