Science fiction

Appearance

(Redirected from Science-fiction)

Science fiction is a genre of fiction. It differs from fantasy in that, within the context of the story, its imaginary elements are largely possible within scientifically-established or scientifically-postulated laws of nature (though some elements in a story might still be pure imaginative speculation).

Quotes

[edit]- Hollywood groupthink is anathema to the nature of sci fi, which is a cerebral philosophical exploration of humankind and puncturing the limits of our imagination. I think the central concept here is that Hollywood, Cap H, is as terrified of sci fi as it is of an alien invasion. And that’s because the studios, as they have been increasingly corporatized, become absolutely risk averse in a way that they haven’t always been.

- Thelma Adams, as quoted by Lewis Beale, “Blame ‘Star Wars’ if You Think Science Fiction Is Brain Dead”, The Daily Beast, (12.15.17).

- John Rieder notes, for example, that the rising thirst for exploration of alien worlds in fiction starting in the nineteenth century, cannot be detached from growing awareness of an impending disappearance of a certain kind of exploration. He remarks: If the Victorian vogue for adventure fiction in general seems to ride the rising tide of imperial expansion, particularly into Africa and the Pacific, the increasing popularity of journeys into outer space or under the ground in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries probably reflects the near exhaustion of the actual unexplored areas of the globe…. Having no place on Earth left for the radical exoticism of unexplored territory, the writers invent places elsewhere.

- Moradewun Adejunmobi, “Introduction: African Science Fiction” , Cambridge Journal of Postcolonial Literary Inquiry, 3(3), September 2016. Cambridge University Press, 2016, University of California, Davis, p. 266.

- Nonetheless, the crosscurrents flowing between representations of alien encounters and the politics of colonialism remain an enduring subject of interest for scholars as evidenced by the many articles examining the films, District 9 and Avatar, as allegories of colonial encounters. Indeed, Neill Blomkamp’s District 9 is arguably the work that first revealed the extent to which it was possible to bring together science fiction and the problematic of postcoloniality for those scholars of African literature and cinema who had not previously given any thought to science fiction as a viable genre for African writers or filmmakers. Since then, scholarly discussions of District 9 have proliferated, but not necessarily in tandem with references to the wider context for African science fiction.

- Moradewun Adejunmobi, “Introduction: African Science Fiction” , Cambridge Journal of Postcolonial Literary Inquiry, 3(3), September 2016. Cambridge University Press, 2016, University of California, Davis, p. 266.

- Science fiction is no more written for scientists than ghost stories are written for ghosts.

- Brian Aldiss, in Penguin Science Fiction (1961), Introduction

- Science fiction is the search for a definition of man and his status in the universe which will stand in our advanced but confused state of knowledge (science), and is characteristically cast in the Gothic or post-Gothic mould.

- Brian Aldiss, Billion Year Spree: The True History of Science Fiction (1973), Ch. 1: "The Origins of the Species"

- Science fiction is that branch of literature that deals with human responses to changes in the level of science and technology.

- Isaac Asimov, Editorial: Extraordinary Voyages in Asimov’s, March-April 1978, p. 6

- Individual science fiction stories may seem as trivial as ever to the blinder critics and philosophers of today — but the core of science fiction, its essence, the concept around which it revolves, has become crucial to our salvation if we are to be saved at all.

- Isaac Asimov, in "My Own View" in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (1978) edited by Robert Holdstock; later published in Asimov on Science Fiction (1981)

- I don't know of any science fiction writer who really attempts to be a prophet. Such authors accomplish their tasks not by being correct in their predictions, necessarily, but merely by hammering home—in story after story—the notion that life is going to be different.

- Isaac Asimov, "Science, Technology and Space: The Isaac Asimov Interview" Pat Stone, Mother Earth News, October 1980.

- Science fiction always bases its future visions on changes in the levels of science and technology. And the reason for that consistency is simply that—in reality—all other changes throughout history have been irrelevant and trivial.

- Isaac Asimov, "Science, Technology and Space: The Isaac Asimov Interview" Pat Stone, Mother Earth News, October 1980.

- The rockets that have made spaceflight possible are an advance that, more than any other technological victory of the twentieth century, was grounded in science fiction… . One thing that no science fiction writer visualized, however, as far as I know, was that the landings on the Moon would be watched by people on Earth by way of television.

- Isaac Asimov, Asimov on Physics (1976), 35. Also in Isaac Asimov’s Book of Science and Nature Quotations (1988), 307.

- If you start putting very large numbers of human brain cells into primates, suddenly you might transform primates into something that has some of the capacities that we regard as distinctively human – speech or other ways of being able to manipulate or relate to a human. These possibilities, at the moment, are largely being explored in fiction but we need to start thinking about them now.

- Tom Baldwin Medical Research Humans Animals Regulation, by Alok Jha, The Guardian, 21, July, 2011

- Two centuries. Two hundred years. That’s how long we’ve had science fiction. From the birth of Frankenstein, to the death of Ursula K. Le Guin. Two hundred years.

Why aren’t there more? Maybe because science fiction, particularly in the golden age years, was just seen as something men did. Maybe because the boys’ club atmosphere put women off. Maybe women weren’t welcome. The first edition of Frankenstein was published anonymously. In 1967, a new science fiction author came on to the scene, James Tiptree Jr. It was at least a decade before the author of dozens of thoughtful, intelligent and often subversive short stories was revealed to be a woman called Alice Sheldon. In an interview with Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction magazine in 1983 she said of her pseudonymous career: “A male name seemed like good camouflage. I had the feeling that a man would slip by less observed. I’ve had too many experiences in my life of being the first woman in some damned occupation.”

Women write science fiction. Women have always written science fiction. But often, they have been ignored, or sidelined, or simply slid under the radar. If they’re very good at writing science fiction, they can get co-opted out of the genre and into “literary fiction”. Take, for example, Margaret Atwood, whose work is out and-out science fiction, from The Handmaid's Tale to Oryx and Crake. Atwood once infamously said her work wasn’t science fiction at all, because that was all about “talking squids in outer space”

But remember this: Mary Shelley was originally tasked to write a ghost story. Instead she invented science fiction with a novel that spoke of horrors yet pierced the heart of humanity.- David Barnett, "Women in science fiction: If Mary Shelley invented the genre why are so few female sci-fi writers household names?", The Independent, (January 25, 2018).

- The hardest theme in science fiction is that of the alien. The simplest solution of all is in fact quite profound — that the real difficulty lies not in understanding what is alien, but in understanding what is self. We are all aliens to each other, all different and divided. We are even aliens to ourselves at different stages of our lives. Do any of us remember precisely what it was like to be a baby?

- Greg Bear, "Introduction to 'Plague of Conscience' ", The Collected Stories of Greg Bear" (2002)

- The link between colonialism and science-fiction is every bit as old as the link between science-fiction and the future. John Rieder in his eye-opening book Colonialism and the Emergence of Science-Fiction notes that most scholars believe that science fiction coalesced "in the period of the most fervid imperialist expansion in the late nineteenth century." Sci-fi "comes into visibility," he argues, "first in those countries most heavily involved in imperialist projects—France and England" and then gradually gains a foothold in Germany and the U.S. as those countries too move to obtain colonies and gain imperial conquests. He adds, "Most important, no informed reader can doubt that allusions to colonial history and situations are ubiquitous features of early science fiction motifs and plots."

- Noah Berlatsky, “Why Sci-Fi Keeps Imagining the Subjugation of White People”, (April 25, 2014).

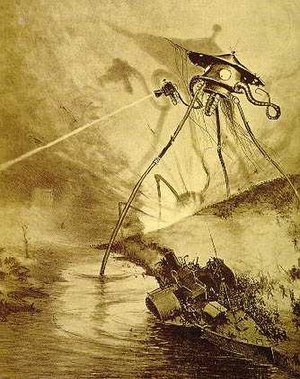

- On the one hand, then, the reverse colonial stories in sci-fi can be used as a way to sympathize with those who suffer under colonialism. It puts the imperialists in the place of the Tasmanians and says, this could be you, how do you justify your violence now? On the other hand, reverse colonial stories can erase those who are at the business end of imperial terror, positing white European colonizers as the threatened victims in a genocidal race war , thereby justifying any excess of violence. Often, though, sci-fi does both at once—as, Rieder argues, Wells does in The War of the Worlds, which both sympathizes with the oppressed and suggests that survival-of-the-fittest colonial exploitation is natural, inevitable, and unstoppable (there is, after all, no talking to the Martians—or, therefore, to the Tasmanians?).

The fact that colonialism is so central to science-fiction, and that science-fiction is so central to our own pop culture, suggests that the colonial experience remains more tightly bound up with our political life and public culture than we sometimes like to think. Sci-fi, then, doesn’t just demonstrate future possibilities, but future limits—the extent to which dreams of what we'll do remain captive to the things we've already done.- Noah Berlatsky, “Why Sci-Fi Keeps Imagining the Subjugation of White People”, (April 25, 2014).

- Fantasies are things that can't happen, and science fiction is about things that can happen.

- Ray Bradbury "Ray Bradbury", Joshua Klein, A.V. Club, Jun 16, 1999.

- Science-fiction works hand-in-glove with the universe.

- Ray Bradbury, "Introduction" in The Circus of Dr. Lao and Other Improbable Stories (1956)

- Science fiction is the most important literature in the history of the world, because it's the history of ideas, the history of our civilization birthing itself. ...Science fiction is central to everything we've ever done, and people who make fun of science fiction writers don't know what they're talking about.

- Ray Bradbury, Brown Daily Herald, March 24, 1995

- People who love science fiction really do love sex.

- Susie Bright "Bright Ideas", interview by Tamara Wieder, Boston Phoenix, February 11, 2005.

- I hate the whole ubermensch, superman temptation that pervades science fiction. I believe no protagonist should be so competent, so awe-inspiring, that a committee of 20 really hard-working, intelligent people couldn't do the same thing.

- David Brin, interview [1] in Locus, March 1997

- Not only is every sci fi innovation kept secret, so that its flaws won't be uncovered and dealt with ahead of time, but the public seldom is invited to share in the New Thing. Or, if they do partake, they are portrayed using it as stupidly as possible, as in the flick Surrogates, where the brilliant invention of remote robotic surrogacy is only used to look good. Talk about a jaundiced view of your fellow citizens.

- David Brin "Our Favorite Cliché: A World Filled With Idiots", DavidBrin.com, 2013.

- Science fiction is the perfect "exploring ground," as it gives us the opportunity to play with different outcomes and strategies before we have to deal with the real-world costs.

- Adrienne Maree Brown Octavia's Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements (2015)

- I am a huge fan of science fiction! Throughout my life I have marveled at the powerful, even transformative nature of speculative storytelling. The influence science fiction storytelling is having in popular culture right now is amazing to behold, and as a genuine fan of the medium, I truly believe we are in a New Age of speculative fiction. There is a pleasing phenomenon developing in the genre recently: the worthy inclusion of voices of color, which are being paid much overdue attention. Why this is important should be self-evident. However, for those sitting way in the back, consider this: we continually create the world we occupy-in our imaginations first, and only afterwards do we make those visions manifest in this world. So it stands to reason that a healthy society is one that respects and honors the voices of ALL of its components. For too long, the voices and visions for our future have been provided, for the most part, by and from a culturally European (if not Eurocentric) perspective. However, there is change afoot. The works of Octavia E. Butler are becoming mainstream, and names like Nnedi Okorafor and Lesley Nneka Arimah are bringing much needed flavor to the narratives that help shape our future.

- LeVar Burton Forward to New Suns: Original Speculative Fiction by People of Color edited by Nisi Shawl (2019)

- I fell into writing it because I saw a bad movie, a movie called Devil Girl from Mars, and went into competition with it. But I think I stayed with it because it was so wide open. It gave me the chance to comment on every aspect of humanity. People tend to think of science fiction as, oh, Star Wars or Star Trek. And the truth is, there are no closed doors, and there are no required formulas. You can go anywhere with it.

- Octavia E. Butler Interview with Democracy Now (2005)

- When I began writing science fiction, when I began reading, heck, I wasn't in any of this stuff I read. The only black people you found were occasional characters or characters who were so feeble-witted that they couldn't manage anything, any way. I wrote myself in, since I'm me and I'm here and I'm writing.

- in New York Times (2000). Attributed in Conversations with Octavia Butler edited by Conseula Francis (2009)

- No less a critic than C. S. Lewis has described the ravenous addiction that these magazines inspired; the same phenomenon has led me to call science fiction the only genuine consciousness-expanding drug.

- Arthur C. Clarke, "Of Sand and Stars", 1983

- Nothing is deader than yesterday's science-fiction.

- Arthur C. Clarke, The Sands of Mars, 1951.

- SF has never really aimed to tell us when we might reach other planets, or develop new technologies, or meet aliens. SF speculates about why we might want to do these things, and how their consequences might affect our lives and our planet.

- John Clute, Science Fiction: The Illustrated Encyclopedia (1995)

- One of the supreme, though unfortunately fairly rare, delights of modern science fiction is that in it you actually can, at times, find Ideas!—real, live, pulsating, coruscating Ideas. Some of them may be on the lame side, but that’s not really important; they still are signs that Someone Has Been Thinking Here. Rare indeed is this phenomenon!

- Groff Conklin, in his introduction to Algis Budrys' story Chain Reaction, in Six Great Short Science Fiction Novels (1960); the story by Budrys was originally published in the April 1957 issue of Astounding.

- [t]his notion leads to one of hard sf’s paradoxes: If our faith in science replaces religious faith, science is co-opted into becoming a religion, which, of course, would be unscientific. . . . The primacy of the sense of wonder in science fiction poses a direct challenge to religion: Does the wonder of science and the natural world as experienced through science fiction replace religious awe? . . . The idea that in the future better and more scientific things will replace all the things we currently need and use—a cosmic belief in an ever-improving standard of living—constitutes what I call the replacement principle of sf.

- Kathryn Cramer, “On Science and Science Fiction“ in Ascent of Wonder: The Evolution of Hard SF. Eds. David G. Hartwell and Kathryn Cramer. New York: Tor, 1994, p. 28.

- Given everything I have read – though I definitely haven’t read everything there is – it seems that Filipino visions of the 22 PSA Newsletter #21 June 2018 Filipino Futures (continued) Articles future unanimously contain sustained social and familial ties. But these visions are also bleak. Dystopias, a stagnant society, and dwindling resources run amok in Philippine science fiction. Does that mean that even if society breaks down, we’ll be all right so long as we have our communities?

However, it seems that Filipino young adult science fiction is overwhelmingly positive in its point of view. Since time immemorial, Philippine culture has often emphasized that its youths are the hope for the future, and Philippine YA science fiction does impress this upon its target market. I, for one, cannot wait to see what the future of Philippine science fiction will bring.- Vida Cruz, Filipino Futures: An Introduction to Philippine Science Fiction, ; Decolonising Speculative Fiction. Eds. Isabelle Hesse and Edward Powell, 2018, p. 22.

- I do watch a lot of television science fiction, and it is a particularly sexless world. With a lot of the material from America, I think gay, lesbian and bisexual characters are massively underrepresented, especially in science fiction, and I'm just not prepared to put up with that. It's a very macho, testosterone-driven genre on the whole, very much written by straight men. I think Torchwood possibly has television's first bisexual male hero, with a very fluid sexuality for the rest of the cast as well. We're a beacon in the darkness.

- Russell T Davies, "Parallel universe". The Age (Melbourne, Australia). 14 June 2007. Retrieved 27 June 2007.

- Science Fiction writers, I am sorry to say, really do not know anything. We can't talk about science because our knowledge of it is limited and unofficial, and usually our fiction is dreadful.

- Philip K. Dick, in "How To Build A Universe That Doesn't Fall Apart Two Days Later" (1978)

- In the six years since Walking the Clouds was published, the world of science fiction has been transformed. The genre, once firmly associated with “the increasing significance of the future to Western techno- cultural consciousness” (Wesleyan Anthology of Science Fiction, qtd in Dillon, 2), has been reclaimed by postcolonial and Indigenous thinkers, who are using the genre to imagine decolonial futures. The increasing global interest in Indigenous and Afro-futuristic narratives demonstrates that this genre, to draw on Dillon’s words, has “the capacity to envision Native futures, Indigenous hopes, and dreams recovered by rethinking the past in a new framework”. But, rather than a recent development, speculative fiction has always belonged to these cultures: as Dillon notes in her introduction, “Indigenous sf [science fiction] is not so new – just overlooked”.

- "Walking the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fiction", edited by Grace L. Dillon. Reviewed by Rebecca Macklin; Decolonising Speculative Fiction. Eds. Isabelle Hesse and Edward Powell, 2018, p. 46.

- Science fiction is, after all, the art of extrapolation.

- Michael Dirda, Introduction to the Everyman's Library edition of The Foundation Trilogy by Isaac Asimov, p. viii.

- As mythmakers, science fiction writers have a double task, the first aspect of which is to make humanly relevant—literally, to humanize—the formidable landscapes of the atomic era. We must trace in the murky sky the outlines of such new constellations as the Telephone, the Helicopter, the Eight Pistons, the Neurosurgeon, the Cryotron. Often enough, in looking about the heavens for a place to install one of these latter-day figures, the mythmaker discovers that the new figure corresponds very neatly with one already there. The Motorcyclist, for instance,is congruent at almost all points with the Centaur, and no pantheon has ever existed without a great-bosomed, cherry-lipped Marilyn who promises every delight to her devotees. But matching old and new isn’t always this easy. Consider the Rocket Ship. Surely it represents something more than a cross between Pegasus and the Argo. What distinguishes the Rocket Ship is that (1) it is mechanically powered and that (2)its great speed carries it out of ordinary space into hyperspace, a realm of indefinable transcendence. My theory is that the contemporary human experience that the myth of the Rocket Ship apotheosizes is that of driving, or riding in, an automobile. We may deplore the use of cars as a means of self-realization and of public highways as roads to ecstasy, but only driver-training instructors would deny that this is what cars are all about. And, by extension, the Rocket Ship. The twenties and thirties, when driving was still a relative novelty, were also the heyday of the archetypal and, in their way, insurpassable—power fantasies of E. E.Smith and other, lesser bards of the Model T. Among adolescents and in countries such as Italy, where car ownership confers the same ego satisfaction as surviving a rite of passage, the Rocket Ship remains the most venerated of sf icons—and not because it embodies a future possibility but because it interprets a common experience.

- Thomas M. Disch, “On SF”, University of Michigan Press, 2005, pp. 22-23.

- Inner Sanctum: Do you have any advice for young writers of science fiction?

Dung: Well, in my opinion, in order to write science fiction, an author has to love both the social and natural sciences and be a skillful writer. Moreover, you should have a deep knowledge of social issues. As a writer, an imaginative mind is necessary to create interesting work. First begin writing short stories, then try with novels. You must combine scientific knowledge and literary skill.

Inner Sanctum: In your opinion, what attracts a reader to science fiction? What do they gain from reading it?

Dung: Science fiction is based on scientific knowledge and imagination. It’s not all impossible. Captain Nemo’s submarine in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea was a prediction. The fact is that we now make them to explore the bottom of the sea.

Readers are attracted to it because they want an intelligent adventure. The stories make them think, imagine and deduce. The stories predict the future of science and even suggest what scientists will invent.- Vu Kim Dung, “Sci-fi writer inspires real world thinking”, Inner Sanctum, Vietnam News, (September, 13/2008).

- "There, Master Niketas," Baudolino said, "when I was not prey to the temptations of this world, I devoted my nights to imagining other worlds. ... There is nothing better than imagining other worlds," he said, "to forget the painful one we live in. At least so I thought then. I hadn't yet realized that, imagining other worlds, you end up changing this one."

- Umberto Eco, Baudolino (2000), p. 99.

- Everyone likes watching an epic sci-fi battle. But whether it’s Star Trek’s Federation versus the Borg, Battlestar Galactica versus the Cylons, or the Rebel Alliance versus the Empire, most veterans are left wondering, “It’s like a thousand years in the future. Why are they fighting like it’s the Bronze Age or something?”

- Carl Forsling, *When It Comes To The Military, SciFi Movies Are Missing The Mark", Task and Purpose, (December 1, 2014).

- The last manned fighter planes that will ever be produced are being manufactured right now. Even with that, pilots in Battlestar Galactica and Star Wars are still dueling at short range as though it was World War II. Larger spaceships (I’m looking at you, Millenium Falcon) even have bubble turrets, with gunners swivelling around like on a B-17.

- Carl Forsling, *When It Comes To The Military, SciFi Movies Are Missing The Mark", Task and Purpose, (December 1, 2014).

- The big starships are even worse, though. They face off like sailing ships of the 18th century, harkening back to days of yore. Star Trek often has starships facing each other at close range, making everyone think, “That Admiral Nelson was really on to something with those sailing ships and broadside cannon battles!” While Star Trek is the archetype, Battlestar Galactica and Star Wars also feature ships facing off like the British against the French at Trafalgar. After travelling billions of miles and using entire solar systems as their battlegrounds, they fight to the death at ranges of a few feet, and frequently make remarkably little use of the fact that they operate in three dimensions.

- Carl Forsling, *When It Comes To The Military, SciFi Movies Are Missing The Mark", Task and Purpose, (December 1, 2014).

- General David Petraeus didn’t personally kill Osama bin Laden. Why does “General” Han Solo lead a squad to take out the shield generator? His friends Admiral Akbar and General Calrissian, along with the rest of the rebel command structure, are above, fighting in a short-range gun battle with Imperial Star Destroyers. Captains Kirk and Picard on Star Trek are one-man SEAL teams fighting the enemy whenever they decide to take a break from their real jobs commanding starships, even though they have crews of literally several hundred other people better suited to fighting than the ship’s captain.

And while we’re talking about it, what’s going on with space invasions? The last opposed beach landing was at Inchon, over 60 years ago. Even that site was picked to avoid the heart of enemy defenses. Amphibious assaults in World War II were successful, but at a huge price. Helicopter tactics have changed to avoid hot landing zones. With most helicopters running over $20 million a pop, they aren’t thrown out lightly. The same is true for amphibious ships. Who knows how much a spaceship costs?

You wouldn’t know by looking at Starship Troopers, Avatar (2009 film), or Star Wars: Episode II. They drop in from space in fragile, helicopter-type vehicles, directly into the enemy defenses. They can literally land anywhere else on the planet, but they choose to land right in front of enemy laser cannon.- Carl Forsling, *When It Comes To The Military, SciFi Movies Are Missing The Mark", Task and Purpose, (December 1, 2014).

- I think the last time I had one of those "CNN moments," where I was slammed right up against the windshield of the present, would have been seeing that federal building in Oklahoma City lying there in its own crater…and getting the idea that something bad had happened in Middle America… Whenever something like this happens…it ups the ante on being a science-fiction writer. It changes the nature of the game.

- William Gibson, 2000, No Maps for These Territories (documentary film, interview format)

- [S]cience fiction implies that the knots of terrestrial racism will eventually loosen because Terrans will have to unite against the aliens, androids, or BEMs [Bug-Eyed Monsters] of the galaxy. Under these circumstances, humans become remarkable for their humanity, not their ethnicity. Robert Scholes seems to have this concept in mind when heremarks that science fiction as a form “has been a bit advanced in its treatment of race and race relations. Because of their orientation toward the future, science fiction writers frequently assumed that America’s major problem in this area—black/white relations—would improve or even wither away.“7 . . .While Scholes and others conveniently assume that distinctions based on race will become invalid in possible future worlds and that it is therefore unnecessary for a character to have a distinct racial background, their presumed total eradication of distinctions based on color or ethnicity seems doubtful short of the Millennium.

- Sandra Y. Govan, The Insistent Presence of Black Folk in the Novels of Samuel R. Delany. Black American Literature Forum 18.2 (1984): p. 44

- I think that science fiction, even the corniest of it, even the most outlandish of it, no matter how badly it's written, has a distinct therapeutic value because all of it has as its primary postulate that the world does change.

- Robert A. Heinlein, "The Discovery of the Future," Guest of Honor Speech, 3rd World Science Fiction Convention, Denver, Colorado (4 July 1941)

- By the closing years of the twentieth century, after the climax of the Cold War,American science fiction reflected a prevalent sense that typical Western subjects were essentially victims of their own society and culture, colonized by vast networks of artificial simulacra, justified in their desire to break through to something more authentic (and recover the priviledge of threatened masculine agency in the process). In the late 1990s, popular science fiction was dominated by awakening-from-simulacrum stories-exemplified by films like The Matrix (1999), Dark City (1998), and The Truman Show (1998)-which all presented narratives (with predecessors reaching back to Phillip K. Dick’s Time Out of Joint [1959] and beyond) in which the main characters found themselves trapped within a false or simulated world striving to gain access to some more real or authentic exterior. Everyday life, in these narratives, was often portrayed as a kind of emasculating ensnarement within post-Fordist systems of command and control. Protagonists like Neo from The Matrix or Tyler Durden from Fight Club struggled against their externally imposed roles within boring and lifeless administrative white-collar jobs focused on keeping the late capitalist system running. There was a general sense in these films and stories that life had somehow become false or artificial, and science fiction literalized the metaphor of being trapped in an alienating system designed to keep one docile, numb, and plugged into an endless cycle of late capitalist production and consumption.

- David M. Higgins, The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction, “Ch. 3 American Science Fiction after 9/11”, Cambridge University Press, (05 February 2015), p.44

- “Arguably, one of the most familiar memes of science fiction is that of going to foreign countries and colonising the natives, and as I’ve said elsewhere, for many of us, that’s not a thrilling adventure story; it’s non-fiction, and we are on the wrong side of the strange-looking ship that appears out of nowhere. To be a person of colour writing science fiction is to be under suspicion of having internalised one’s colonisation”.

- So Long Been Dreaming: Postcolonial Science Fiction and Fantasy, edited by Nalo Hopkinson and Uppinder Mehan Reviewed by Andrew Stones, in Decolonising Speculative Fiction. Eds. Isabelle Hesse and Edward Powell, 2018, p. 42.

- What we get from science fiction—what keeps us reading it, in spite of our doubts and occasional disgust—is not different from the thing that makes mainstream stories rewarding, but only expressed differently. We live on a minute island of known things. Our undiminished wonder at the mystery which surrounds us is what makes us human. In science fiction we can approach that mystery, not in small, everyday symbols, but in the big ones of space and time.

- Damon Knight, “Critics”, Visions of Wonder. Eds. David G. Hartwell and Milton T. Wolf. New York:Tor, 1996, p. 15.

- Science fiction is an internationalist genre. When a novel is set in a galaxy far, far, away current geopolitical boundaries don't have a lot of meaning.

However, Kaufman says there was a time when you could sell a novel set in space, but you couldn't sell a science fiction novel set in Australia.- Sarah L'Estrange, “Australian science fiction authors feel let down by local publishers”, ABC, Books and Arts, (8 Mar 2017).

- From a social point of view most SF has been incredibly regressive and unimaginative. All those Galactic Empires, taken straight from the British Empire of 1880. All those planets — with 80 trillion miles between them! — conceived of as warring nation-states, or as colonies to be exploited, or to be nudged by the benevolent Imperium of Earth towards self-development — the White Man’s Burden all over again. The Rotary Club on Alpha Centauri, that’s the size of it.

- Ursula Le Guin, “American SF and the Other”, 1975 essay.

- Science-fiction is a literary province I used to visit fairly often; if I now visit it seldom, that is not because my taste has improved but because the province has changed, being now covered with new building estates, in a style I don't care for. But in the good old days I noticed that whenever critics said anything about it, they betrayed great ignorance. They talked as if it were a homogeneous genre. But it is not, in the literary sense, a genre at all. There is nothing common to all who write it except the use of a particular 'machine'. Some of the writers are of the family of Jules Verne and are primarily interested in technology. Some use the machine simply for literary fantasy and produce what is essentially Märchen or myth. A great many use it for satire; nearly all the most pungent American criticism of the American way of life takes this form, and would at once be denounced as un-American if it ventured into any other. And finally, there is the great mass of hacks who merely 'cashed in' on the boom in science-fiction and used remote planets or even galaxies as the backcloth for spy-stories or love-stories which might as well or better have been located in Whitechapel or the Bronx. And as the stories differ in kind, so of course do their readers. You can, if you wish, class all science-fiction together; but it is about as perceptive as classing the works of Ballantyne, Conrad and W. W. Jacobs together as 'the sea-story' and then criticising that.

- C. S. Lewis, An Experiment in Criticism (1961), XI: "The Experiment"

- It is absurd to condemn them [science fiction stories] because they do not often display any deep or sensitive characterization. They oughtn't to. … Every good writer knows that the more unusual the scenes and events of his story are, the slighter, more ordinary, the more typical his persons should be. Hence Gulliver is a commonplace little man and Alice is a commonplace little girl. If they had been more remarkable they would have wrecked their books. The Ancient Mariner himself is a very ordinary man. To tell how odd things struck odd people is to have an oddity too much; he who is to see strange sights must not himself be strange.

- C. S. Lewis, "On Science Fiction", 24 November 1955 talk to the Cambridge University English Club on; published posthumously in Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories (1966)

- With Arab literature so focused on classical themes, an Orwellian allegory, for instance, would tackle the present and envision a future in a more clandestine fashion than a straightforward political attack.

Sultana's Dream is an example of such critique. Written in 1905 by a Muslim feminist writer and social reformer who lived in British India, it is one of the earliest examples of feminist science fiction, and is a sort of gender-based Planet of the Apes where the roles are reversed and the men are locked away in a technologically advanced future.- Nesrine Malik, "What happened to Arab science fiction?", The Guardian (30 July 2009).

- I like to present my characters—whether they are in the past or in the future—with interesting moral choices, and it seems to me that science-fiction writers are, or should be, the prophets and moralists of today. I am fairly well up on the biological sciences, but I am deeply uninterested in gadgets. A writer's job is to write about people with sympathy and insight.

- Naomi Mitchison, in Anthony Wolk, "Challenge the Boundaries: An Overview of Science Fiction and Fantasy," The English Journal 79 (1990), p. 27.

- Brian Rollins: You're one of the few sci-fi writers in Hollywood to use religion in your shows. What kind of resistance/acceptance do you see from industry insiders and fans?

- Moore: I was amazed that I didn’t get a lot of resistance from the industry. For whatever reason, SCI FI Channel and Universal just let me run with it on Battlestar. They didn’t have problems with it. They had other problems, but they didn’t have any problems with the religious stuff in the show. And the fans, it was an interesting reaction. There’s a surprising core of fandom that just hates any kind of religion in their science fiction. They really don’t want to mix these things together. I’m not quite clear what that’s about and why they’re so opposed to mixing these things. It becomes a very purist argument. People will say, “If there’s any kind of religion in it, it’s not science fiction anymore.” Well, I don’t really buy that. People believe in religions and there are weird, mysterious things that happen in the universe. Why not play with that, too? Why isn’t that just as valid as everything else that’s part of the human condition, which is theoretically what sci-fi is supposed to be exploring.

- Ronald D. Moore, "You Ask The Q's, Ronald D. Moore Answers, Part 2", StarTrek.com, April 03, 2013.

- The whiteness of speculative fiction is something I have myself done extensive research on, beginning with the earliest examples of speculative fiction first set in, and then originating from, Southern Africa – H. Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines in 1885.

- Alan Muller, Decolonising Speculative Fiction in South Africa; Decolonising Speculative Fiction. Eds. Isabelle Hesse and Edward Powell, 2018, p. 31.

- This linguistic progress has not been limited to literature. The 2017 BRICS (an association of five major emerging national economies: Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa Film Festival held in Chengdu, China saw the debut of Jahmil XT Qubeka’s 20 minute short film, Stillborn, which follows the android Nobomi SX1 as she tries to uncover the cultural past of the now extinct humans that created her. With dialogue entirely in isiXhosa, the film is the first South African science fiction film not in English.

- Alan Muller, Decolonising Speculative Fiction in South Africa; Decolonising Speculative Fiction. Eds. Isabelle Hesse and Edward Powell, 2018, p. 31.

- Sci-fi can be succinctly defined as speculation, whether based on established scientific facts or on logical pseudo-facts consistent with the framework of the fiction in question, involving smelly green pimply aliens furiously raping or eating, or both, beautiful naked bare-breasted chicks, covering them in slime, red, oozing, living slime, dribbling from every horrific orifice, squeezing out between bulbous pulpy lips onto the sensuous velvety skin of the writhing sweating slave-girls, their bodies cut and bruised by knotted whips brandished by giant blond vast-biceped androids called Simon, and written in the Gothic mode.

- Peter Nicholls, True Rat 7 (1976)

- Science fiction has existed in China almost as long as it existed in the West. It began in the late-Qing Dynasty, with scholars translating the works of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells into Chinese. Among such translators was Lu Xun, the father of modern Chinese literature himself. Of course, tales of the strange and mysterious permeate Chinese literature from its ancient origins on, but the first work generally recognized as an original Chinese science fiction story was Colony of the Moon (月球殖民地). It was published as a serial from 1904 to 1905 under the pen name Huangjiang Diaosou (荒江钓叟), which means “Old Fisherman by a Deserted River.” Many other works were published during this early-twentieth-century period. The genre was perceived to have literary merit through its ability to incite interest among readers in the rapidly evolving fields of science and technology, in which China was involved in a game of catch-up.

- Carly O'Connell, "The rise of Chinese sci-fi: Part 1", Asia Times, January 3, 2003.

- Sf cinema is undeniably dominated by the American film industry, at least in Western countries and since the end of World War II. Not only are the majority of sf films released each year produced in the US, but many of them are Hollywood blockbusters made with the biggest of budgets, while nations with very rich cinematic histories, such as France and Italy, have made comparatively few contributions in the genre. There is, however, a not-insignificant corpus of sf cinema produced in Latin America. These films have mostly been ignored by critics and academics, both nationally and internationally, and only in the past few years have they begun to show signs of being rediscovered.

- Mariano Paz, “South of the future: An overview of Latin American science fiction cinema” , Science Fiction Film and Television, Liverpool University Press, Volume 1, Issue 1, Spring 2008, pp. 81.

- Science fiction, speculative fiction, whatever you want to call it, is one of the ways to explore social issues in fiction. You can explore what it's going to be like if current trends continue. You can change a variable and see what that does.

- Marge Piercy Interview in My Life, My Body (2015)

- the most fruitful ways to approach the future for me are speculative fiction or utopian fiction. Isaac Asimov once said that all science fiction falls into three categories: What if, If only, and If this continues.

- Marge Piercy "WHY SPECULATE ON THE FUTURE?" My Life, My Body (2015)

- Of course, science-fiction is an expensive genre to produce. VFX, starships, superheroes, these all cost money. And it’s true Africa can’t yet compete with Hollywood feature films in terms of scale the way it can in terms of imagination. It may take some getting used to, watching a very different sort of Sci-Fi, but these films throw up challenging new ways of thinking about Sci-Fi socially, politically and in terms of what our real future might look like. The closest place to find what we’re used to watching, though, would be South Africa, where artists have used the short, rather than feature film format to explore ideas of how we live in the modern day, shaped ever-more by technology.

Another thing everyone says when one brings up African sci-fi is, “You mean like District 9?” And, yes, we do mean like that. A lot like that, actually. As a nation, we like to claim District 9, but let’s face it the money and the audience were American.- David Platt, "Future Myths: An Intro to African Sci-fi Films", Indie Channel.

- In schools, for example, there are courses in the criticism of literature, art criticism, and so forth. The arts are supposed to be 'not real.' It is quite safe, therefore, to criticize them in that regard -- to see how a story or a painting is constructed, or more importantly, to critically analyze the structure of ideas, themes, or beliefs that appear, say, in the poem or work of fiction. When children are taught science, there is no criticism allowed. They are told, 'This is how things are.' Science's reasons are given as the only true statements about reality, with which no student is expected to quarrel. Any strong intellectual explorations or counter versions of reality have appeared in science fiction, for example. Here scientists, many being science-fiction buffs, can channel their own intellectual questioning into a safe form. 'This is, after all, merely imaginative and not to be taken seriously.'

- Jane Roberts, in The God of Jane: A Psychic Manifesto, p. 145-146

- Science fiction rarely is about scientists doing real science, in its slowness, its vagueness, the sort of tedious quality of getting out there and digging amongst rocks and then trying to convince people that what you're seeing justifies the conclusions you're making. The whole process of science is wildly under-represented in science fiction because it's not easy to write about. There are many facets of science that are almost exactly opposite of dramatic narrative. It's slow, tedious, inconclusive, it's hard to tell good guys from bad guys — it's everything that a normal hour of Star Trek is not.

- Kim Stanley Robinson, interview [2] in Locus, September 1997

- For the last three decades, the arbiters of taste in science fiction have followed the lead of the mainstream literary publishing industry. When that industry embraced modernist literature—literature with little or no narrative, literature that attempted to capture “real life” in beautiful prose—the industry turned its back on storytelling. Science fiction, in attempt to gain legitimacy, did the same. Too many books, published from the late sixties to now, are stylistically brilliant and essentially dull.

- Kristine Kathryn Rusch, Editorial, in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, March 1997, p. 7

- There are plenty of images of women in science fiction. There are hardly any women.

- Joanna Russ "The Image of Women in Science Fiction" (1970)

- In the field of science fiction or fantasy, morality—when it enters a book at all—is almost always either thoughtlessly liberal (you can’t judge other cultures) or thoughtlessly illiberal (strong men must rule) or just plain thoughtless (killing people is bad).

- Joanna Russ "Books" (review column), The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, December 1968

- The futurist fiction literary genre is a 20th-century phenomenon. According to Gregory Benford, a physicist and a much-laureled hard SF author, “[S]cience fiction arose in a time affected by science’s unsettling relations about ourselves, about our position in the naturalorder—and by relentless technology, science’s burly handmaiden. Science fiction has tried to grapple with ideas which disturb our sense of being at home in the world” (16). Kathryn Cramer sets the beginning of futurist fiction proper in the 1920s (25), as does David G. Hartwell, who claims futurist fiction began when Hugo Gernsback, editor for Amazing Stories, labeled the newgenre as “scientifiction” in 1926 (31, 37). During the 1920s, Hartwell maintains, a growing split developed between high- (Modernist) and low- (popular or paraliterary) literature. Futurist fiction took the brunt of the split as H. G. Wells lost his long aesthetic battle to Henry James, who championed “art for art’s sake.” Wells proceeded to become a popular and successful author and one of the first authorities on futurist fiction technique. As Well’s proto-genre took shape, it evolved in antithesis to Jamesian Modernism by rejecting the valorization of style and innovative content (Hartwell 36). According to Hartwell, clear definitions for futurist fiction would not arise until the mid-1930s when John W. Campbell, who prized scientific integrity in the new genre, assumed editorial responsibility for Astounding Stories (37).

- Gregory E. Rutledge, “FUTURIST FICTION & FANTASY: The Racial Establishment”, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, September 2006, p. 237.

- For Samuel R. Delany, Jr., speculative fiction, as he preferred to call the genre, is radically different from standard fiction for reasons ranging from syntactic variation to thematic vistas to authorial function (Science447-51). Joanna Russ agrees with Delany’s assessment. She notes that futurist fiction is highly didactic, and for any didactic work to be understood by its reader-critics, they must grasp its constitutive principles. Thus, Russ maintains, as science generates new paradigms, the vast majority of contemporary literary critics who lack a sufficient scientific understanding cannot credibly assay speculative fiction (556-67). Although Russ’ polemic can be applied to futurist fiction generally, it is most directly relevant to hard SF. Hard SF valorizes the central tenet that scientific plausibility must constitute the guiding framework for the story. Although John W. Campbell promulgated its tenets in the 1930s, hard SF would not become a distinct FFF subgenre until the late 1950s ormid-1960s. Some critics see the establishment of hard SF as a conservative reaction to the New Wave literary movement, which embraced extra-scientific influences.

- Gregory E. Rutledge, “FUTURIST FICTION & FANTASY: The Racial Establishment”, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, September 2006, p. 238.

- The question of more pointed significance to the Black community is whether the advent of and devotion to science—which has been used, as a science fiction, throughout the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries to justify slavery and the inferiority of Blacks—will undercut religion in the African diaspora. Religion has long occupied the central role in the freedom struggle of the Black community (Du Bois, Souls 211-20; Franklin 92-95,146-47; Woodson 52-53). According to Hartwell, much of futurist fiction in the 1940s and 1950s elevated scientific knowledge above other systems of thought, and thus “a lot of it was xenophobic, elitist, racist, and psychologically naive” (38). Apparently, not even the recent unmasking of the widespread eradication or co-opting of diasporic scientific accomplishments engendered by the wave of Black studies programs initiated in the early 1970s has undone the Black community’s suspicion toward science.

- Gregory E. Rutledge, “FUTURIST FICTION & FANTASY: The Racial Establishment”, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, September 2006, p. 241.

- Real science is as amenable to exciting and engrossing fiction as fake science, and I think it is important to exploit every opportunity to convey scientific ideas in a civilization which is both based upon science and does almost nothing to ensure that science is understood.

- Carl Sagan, Broca's Brain (1979), Chapter 9, “Science Fiction—A Personal View” (p. 166)

- Many scientists deeply involved in the exploration of the solar system (myself among them) were first turned in that direction by science fiction. And the fact that some of that science fiction was not of the highest quality is irrelevant. Ten-year-olds do not read the scientific literature.

- Carl Sagan, Broca's Brain (1979), Chapter 9, “Science Fiction—A Personal View” (p. 172)

- Situated within the considerable body of creative material that is set in a future Australia, only a small body of this literary work has been authored by First Nations writers. These works include Archie Weller’s 1999 novel Land of The Golden Clouds , Alexis Wright’s 2013 novel The Swan Book, Ambellin Kwaymullina’s young adult Tribe series, Ellen van Neervan’s 2014 short story “Water” from Heat and Light, and Claire G. Coleman’s 2017 novel Terra Nullius.

- Mykaela Saunders, Living and Dying Countries: Ecocide, Consciousness & Agency in First Nations Futurism; in Decolonising Speculative Fiction. Eds. Isabelle Hesse and Edward Powell, 2018, p.7.

- It is said that science fiction and fantasy are two different things. Science fiction is the improbable made possible, and fantasy is the impossible made probable.

- Rod Serling The Twilight Zone, "The Fugitive" (1962)

- Since the summer of 2012, the patent war between Samsung and Apple has been raging in almost every media outlet in South Korea, reminding the public of their country’s status as the newly risen IT capital in the global community. This recognition indeed extends far beyond the Korean borders; in the recent film Cloud Atlas (2012), for instance, the Western gaze shifts its focus to (Neo-) Seoul as the site of our time’s techno-orientalist future-scape, instead of adhering to the classic imageries of Tokyo or Hong Kong as we have seen in Blade Runner (1982) or Ghost in the Shell (1995). Curiously, however, science fiction as a literary representation of the technologized science South Korea thrives on nowadays never appears to have gained traction in Korea’s own cultural imaginary.

- Haerin Shin, "The Curious Case of South Korean Science Fiction: A Hyper-Technological Society’s Call for Speculative Imagination", Azalea: Journal of Korean Literature & Culture, University of Hawai'i Press, Volume 6, 2013, pp. 81-85

- Remember that Jules Verne was a sort of Shakespeare of science fiction, and we would feel derelict if we did not give his stories in our columns.

- T. O'Conor Sloane in the "Discussions" column, Amazing Stories, January 1927. (This quote is notable for being the first "modern use" of the term science fiction.)[1]

- The science fiction approach doesn't mean it's always about the future; it's an awareness that this is different.

- Neal Stephenson, "A Conversation With Neal Stephenson", SF Site, 1999.

- In most Latin American countries, SF&F fiction, both in literature and cinema, tends to be underrated, neglected or simply overlooked by critics and scholars. In Brazil, for instance, SF&F suffers from historical prejudices held by the academic milieu, editorial markets and audiovisual industries. For instance, Mary Elizabeth Ginway suggests that the invisibility of Brazilian science fiction literature could be ascribed to the overrating of the realist novel in Brazil. According to Ginway, Brazilian science fiction still suffers from elitist cultural attitudes that prevail in Brazil; the idea that a “Third World” country could not genuinely produce such a genre.

Nevertheless, Latin American SF&F does exist, although it is seldom detected by most film critics, scholars, historians, and perhaps, even by major audiences. This panorama could be due to limited film budgets, and the lack of consistent film industries in Latin America (understanding “industry” in its most orthodox sense). In summary, the alleged “invisibility” of Latin American SF&F film might be partially, if not entirely, explained by historical instability affecting the Latin American film industry. Thus, cultural biases have sided with infrastructural issues in the preclusion of Latin American SF&F cinema.- Alfredo Suppia, "The Quest for Latin American Science Fiction & Fantasy Film", Frames Cinema Journal, University of St. Andrews.

- There is no such thing as science fiction, there is only science eventuality.

- Steven Spielberg, The Making of Jurassic Park [specific citation needed]

- And there, right there, is the area in which science fiction leads the literary side of its life. It is the job of the science-fiction writer to take the utterly fantastic, if need be, and make it seem as real as a copy of today's tabloid newspaper folded to the sports section. To the extent that he succeeds in this he is a good science-fiction writer, and to the extent that he fails to make the story believable he is a bad one, be it ever so full of faster-than-light gimmicks and futuristic individuals with triple brains and mechanical genitalia.

- William Tenn, On the Fiction in Science-Fiction in Of All Possible Worlds, p. 7 (originally published in Science Fiction Adventures, March 1954)

- Science fiction, thus considered, is not a mere pocket in the varicolored vest of modern writing; it is a new kind of fiction, the beginnings of a long-delayed revolution in letters consequent upon the revolutions that the last two hundred years have witnessed in science, industry, and politics. By this I do not at all mean that it is the only possible literature of the present time, just that it is the type most peculiar to it, most indicative of its larger intellectual trends.

- William Tenn, ibid, p. 10

- Whether or not the science fiction will eventually develop a Shakespeare, I would not dare to predict. But I do claim that it is a literature produced by our times as much as Shakespeare's was by his. And its unfortunate, frequent vulgarities can well be equated with the vulgarities and plebeian absurdities of much Elizabethan writing, both reflecting the primitive vitality of the mass audience that responded to them. It is, of course, in any age, only moribund fiction that is polished to a point of antisepsis, and that will, in losing touch with its audience, “lose the name of action.” This new medium has as yet lost neither.

- William Tenn, ibid, pp. 11-12

- The human mind is lit by an elemental sense of wonder, a probing, restless curiosity that is our primate heritage and that from its beginnings has sought a knowledge, some knowledge, of the future. To satisfy that need there has come into being a massive and thoroughly modern creation, science fiction, the literature of extrapolative, industrial man.

- William Tenn, ibid, p. 12

- Dark matter as a metaphor offers us an interesting way of examining blacks and science fiction. The metaphor can be applied to a discussion of the individual writers as black artists in society and how that identity affects their work. It can also be applied to a discussion of their influence and impact on the sf genre in general. While the "black sf as dark matter" metaphor is novel, the concept behind it is not. The metaphor is neither farfetched nor uncommon if one considers popular themes within the black literary tradition. An excellent example is Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man (1945), a novel that introduced the idea of black invisibility...It is my sincere hope that Dark Matter will help shed light on the sf genre, that it will correct the misperception that black writers are recent to the field, and that it will encourage more talented writers to enter the genre.

- Sheree Thomas Dark Matter: A Century of Speculative Fiction from the African Diaspora (2000)

- Science fiction is a very big canvas for a film maker to work on because if you are doing a drama, society imposes its rules on you and you have to live by those guidelines; more or less. But in science fiction you get to make up the rules of the world you create.

- David Twohy "Pitch Black: David Twohy and Vin Diesel interview", SBS, May 17, 2000.

- The "hard" science-fiction writers are the ones who try to write specific stories about all that technology may do for us. More and more, these writers felt an opaque wall across the future. Once, they could put such fantasies millions of years in the future. Now they saw that their most diligent extrapolations resulted in the unknowable … soon.

- Vernor Vinge, "The Coming Technological Singularity" (1993)

- I have been a soreheaded occupant of a file drawer labeled "Science Fiction" ever since, and I would like out, particularly since so many serious critics regularly mistake the drawer for a urinal.

- Kurt Vonnegut, The New York Times Book Review, 5 September 1965; reprinted in Wampeters, Foma & Granfalloons (1974)

- I advance the thesis that science fiction brings teleology to science, tells of origins and destinies, both asserts and denies “the expectancy of the familiar,” is—in brief—both mythopoeic and mythoclastic.

- Robin Scott Wilson, The Terrific Play of Forces Natural and Human (1971), in Robin Scott Wilson (ed.), Clarion (p. 210)

- It is as romantic myth (“as connoting le roman, or deliberately contrived story”) that I believe science fiction finds its functional definition.

- Robin Scott Wilson, The Terrific Play of Forces Natural and Human (1971), in Robin Scott Wilson (ed.), Clarion (p. 210)

- We hope it will not be long before we may have other works of Science-Fiction [like Richard Henry Horne’s ‘‘The Poor Artist’’], as we believe such books likely to fulfill a good purpose, and create an interest, where, unhappily, science alone might fail. [Thomas] Campbell says, that ‘‘Fiction in Poetry is not the reverse of truth, but her soft and enchanting resemblance.’’ Now this applies especially to Science-Fiction, in which the revealed truths of Science may be given, interwoven with a pleasing story which may itself be poetical and true—thus circulating a knowledge of the Poetry of Science, clothed in a garb of the Poetry of life.

- William Wilson, A Little Earnest Book upon a Great Old Subject (1851)

- This is the first recorded use of the term science fiction in history.[1]

- “As a mixed-race Asian American, I am used to and feel comfortable existing as ‘other.’ The universes to be found in science fiction are both exciting, and also feel like home,” says Seattle artist Stasia Burrington, whose work is featured in the exhibit. “It feels natural to explore and expand definitions of our reality, and possibilities of what’s to come. I feel like we (contemporary artists) are in an exciting place.”

Burrington created an alien landscape mural that touches on the theme of how Asians relate to sci-fi. Some immigrants feel a connection to the alien stories in classic sci-fi, leaving home and traveling to a new planet where you don’t quite belong. Others reject the idea that they are “aliens” and don’t want to be portrayed that way. This diversity of viewpoints is an important part of the exhibition experience.

Many artists focused on using sci-fi ideas and creating art through an Asian Pacific American lens. “I was excited about the challenge of taking sci-fi/fantasy ideas and manifest it in a concrete, artistic form through an Asian American lens. I used the word coined by author Ken Liu, ‘Silkpunk,’ to guide and inform elements of my hanging sculpture,” says June Sekiguchi, another local artist whose work is showcased in the exhibit.

As evidenced by the number of Asian Americans who work behind the scenes to make sci-fi the massive success it is today, the community has a far greater impact on the genre than is visible on the surface. Exhibits like “Worlds Beyond” offer context and a glimpse into the worlds they help create.- Wing Luke Museum, “Explore the impact of Asian Pacific Americans on science fiction”, The Seattle Times, (February 4, 2019).

- Science fiction is the branch of literature that perceives the universe through the widest-angle lens. Unlike the mainstream of literature, which attempts, more or less, to depict the real world and real people in present or historic situations with the maximum amount of verisimilitude, science fiction acknowledges from the start that it is fantasy, that it is not depicting that which is or that which has been but is engaging in assaying the actions of people and things against backgrounds of limitless imagination.

- Donald A. Wollheim, Introduction in Best From the Rest of the World (1976), ISBN 0-87997-343-9, p. 7

- Science fiction has always been with us—writers have always speculated on the horizons of the not-yet-proven—and examples can be culled from the dawn of written lore and are to be found in all periods of storytelling. To some extent this is a type of escapism and to some extent it is a form of genetic curiosity: people always want to know what is over the next hill and beyond the farthest horizon rise and at the end of the rainbow. When tellers of tall tales could no longer convince an audience not quite as gullible as our less informed ancestors, the art of science fiction came into being. Extend what we know a little further, advance the line of what could be, bring in the “if this goes on” factor—and we have science fiction. Fantasy designed as reality.

- Donald A. Wollheim, Introduction in Best From the Rest of the World (1976), ISBN 0-87997-343-9, pp. 7-8

- True epics of course are few and historically well spaced, but that slightly more mundane ingredient, the speculative impulse, be it of Classic, Christian or Renaissance shading, which ornamented Western literature with romances, fables, exotic voyages and utopias, seemed to me basically the same turn of fancy exercised today in science fiction, working then with the only objects available to it. It took the Enlightenment, it took science, it took the industrial revolution to provide new sources of idea that, pushed, poked, inverted and rotated through higher spaces, resulted in science fiction. When the biggest, the most interesting ideas began emerging from science, rather than from theology or the exploration of new lands, hindsight makes it seem logical that something like science fiction had to be delivered.

- Roger Zelazny, Some Science Fiction Parameters: A Biased View (1975), reprinted in Unicorn Variations (1983), ISBN 0-380-70287-8, p. 245

- Science fiction narratives appeared in the North Korean children's magazine Adong munhak between 1956 and 1965, and they bear witness to the significant Soviet influence in this formative period of the DPRK. Moving beyond questions of authenticity and imitation, however, this article locates the science fiction narrative within North Korean discourses on children's literature preoccupied with the role of fiction as both a reflection of the real and a projection of the imminent, utopian future. Through a close reading of science fiction narratives from this period, this article underscores the way in which science, technology, and the environment are implicated in North Korean political discourses of development, and points to the way in which these works resolve the inherent tension between the desirable and seemingly contradictory qualities of the ideal scientist—obedient servant of the collective and indefatigable questioner—to establish the child-scientist as the new protagonist of the DPRK.

- Dafna Zur, "Let's Go to the Moon: Science Fiction in the North Korean Children's Magazine "Adong Munhak", 1956-1965", The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 73, No. 2 (MAY 2014), pp. 327-351

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]External links

[edit]Encyclopedic article on Science fiction on Wikipedia

The dictionary definition of science fiction on Wiktionary

Media related to Science fiction on Wikimedia Commons

Works related to Category:Science fiction on Wikisource