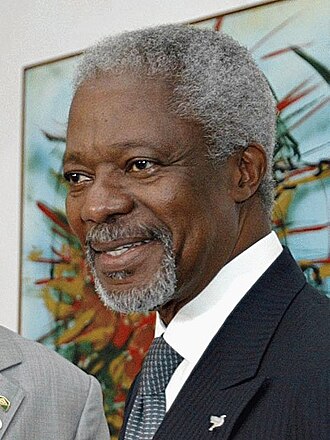

Kofi Annan

Appearance

Kofi Atta Annan (8 April 1938 – 18 August 2018) was a Ghanaian diplomat who served as the seventh Secretary-General of the United Nations from January 1997 to December 2006. Annan and the United Nations were the co-recipients of the 2001 Nobel Peace Prize.

Quotes

[edit]

- “The world is not ours to keep. We hold it in trust for future generations.”

- You can do a lot with diplomacy, but with diplomacy backed up by force you can get a lot more done.

- Press conference regarding the use of force to gain compliance from Saddam Hussein (24 February 1998)

- Eradication of extreme poverty has been identified as a priority, and specific targets have been set for prescribed measures. Many said the potential benefits of globalization are understood but people have yet to feel them. It is agreed that part of the solution lies in sovereign States giving priority to the needs of their people, especially the poorest. States, however, must work with the private sector and civil society to solve the problems of globalization. A more equitable world economy has been called for, one where those who have more do more for those who have less.

- Address given at the United Nation's General Assembly Millennium Summit (8 September 2000)

- I think that my darkest moment was the Iraq war, and the fact that we could not stop it.. I worked very hard — I was working the phone, talking to leaders around the world... The U.S. did not have the support in the [UN] Security Council. So they decided to go without the council. But I think the council was right in not sanctioning the war...Could you imagine if the U.N. had endorsed the war in Iraq, what our reputation would be like? Although at that point, President (George W.) Bush said the U.N. was headed toward irrelevance, because we had not supported the war. But now we know better.

- Quoted in Kofi Annan, former UN secretary general, dies aged 80 (CNBC) (18 August 2018)

- He is very calm—very, very calm. Never raises his voice. Well-informed, contrary to the sense outside that he is ill-informed and isolated. And decisive.

- On Saddam Hussein, Press conference (24 February 1998)

- Unless the Security Council is restored to its pre-eminent position as the sole source of legitimacy on the use of force, we are on a dangerous path to anarchy.

- Speech at the centennial of the International Peace Conference (19 May 1999)

- We may have different religions, different languages, different colored skin, but we all belong to one human race. We all share the same basic values.

- As quoted in Simply Living: The Spirit of the Indigenous People (1999) edited by Shirley A. Jones

- More than ever before in human history, we share a common destiny. We can master it only if we face it together. And that, my friends, is why we have the United Nations.

- You have said that your first priority is the eradication of extreme poverty.

- So spoke United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan on September 8, 2000, to an assembly of the world’s most powerful men and women. WOL

- I hope we do not see another Iraq-type operation for a long time — without UN approval and much broader support from the international community.

- "Iraq war illegal, says Annan" BBC News (16 September 2004); when asked if the invasion of Iraq was illegal, he replied "Yes, if you wish. I have indicated it was not in conformity with the UN charter from our point of view, from the charter point of view, it was illegal."

- Well, the issue of a standing UN army has been raised by many because, quite frankly, the way we operate today is like telling Ottawa that I know you need a fire station but we will build one when the fire breaks. We have no army. When the crisis breaks then we begin to put an army together. We go around to governments and begin asking for troops. The question with a standing UN army is that it raises issues of budget issues, legal issues, where do you place it, under what jurisdiction? And the big boys, big countries don't want it. The smaller countries are also nervous.

- These values: compassion; solidarity; respect for each other - already exist in all our great religions. We can begin by reaffirming and demonstrating that the problem is not the Koran, nor the Torah nor the Bible. As I have often said, the problem is never the faith. It is the faithful, and how we behave towards each other. It is these great, enduring and universal principles which are also enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. We can use these values – and the frameworks and tools we have based on them - to bridge divides and make people feel more secure and confident of the future.

- World Civilisations: “Bridging the World’s Divides”. Lecture given at the British Museum London.

- The Lord had the wonderful advantage of being able to work alone.

- Answer when he was asked why he had not yet reformed the U.N. an its agencies after five months, given that God had taken only seven days to create the universe. As quoted in TIME Magazine (1997), edited by Briton Hadden, Henry Robinson Luce. Time Inc. Volume 149. Issues 2-8. p. 24. Also found in George Antwi (2012), "The Words of Power", Booksmango, p. 103.

- Variant said by Kofi Annan himself during the "Desmond Tutu Annual International Peace Lecture":"Mr. ambassador, you are right. But God had the unique advantage: He worked alone." (He explains that the question was made by the Russian Ambassador of the U.N. at that time).

- The report [by a UN commission on Darfur] demonstrates beyond all doubt that the last two years have been little short of hell on earth for our fellow human beings in Darfur.

- The intention was really to do something dignified, something that is honest and reflects the work that this Organization does. And it is with that spirit that the producers and the directors approached their work, and I hope you will all agree they have done that.

- On the film The Interpreter, from "Secretary-General's press encounter" (19 April 2005)

- We don’t need any more promises. We need to start keeping the promises we already made.

- Secretary-General Kofi Annan’s message for the New Year, 2004. un.org

- There are a great number of peoples who need more than just words of sympathy from the international community. They need a real and sustained commitment to help end their cycles of violence, and launch them on a safe passage to prosperity.

- The international community . . . allows nearly 3 billion people—almost half of all humanity—to subsist on $2 or less a day in a world of unprecedented wealth.

- Awake! magazine, May 22, 2002; Can Globalization Really Solve Our Problems?

- We need to create a world that is equitable, that is stable and a world where we bear in mind the needs of others, and not only what we need immediately. We are all in the same boat.

- Gender equality is critical for the development and peace of every nation.

- Quoted in: Kabir, Hajara Muhammad (2010). Northern women development. [Nigeria]. ISBN 978-978-906-469-4. OCLC 890820657.

- When women thrive, all of society benefits and succeeding generations are given a better start in life.

- Quoted in: Kabir, Hajara Muhammad (2010). Northern women development. [Nigeria]. ISBN 978-978-906-469-4. OCLC 890820657.

Nobel lecture (2001)

[edit]

- Today, in Afghanistan, a girl will be born. Her mother will hold her and feed her, comfort her and care for her — just as any mother would anywhere in the world. In these most basic acts of human nature, humanity knows no divisions.But to be born a girl in today's Afghanistan is to begin life centuries away from the prosperity that one small part of humanity has achieved. It is to live under conditions that many of us in this hall would consider inhuman.

I speak of a girl in Afghanistan, but I might equally well have mentioned a baby boy or girl in Sierra Leone. No one today is unaware of this divide between the world’s rich and poor. No one today can claim ignorance of the cost that this divide imposes on the poor and dispossessed who are no less deserving of human dignity, fundamental freedoms, security, food and education than any of us. The cost, however, is not borne by them alone. Ultimately, it is borne by all of us — North and South, rich and poor, men and women of all races and religions.

Today's real borders are not between nations, but between powerful and powerless, free and fettered, privileged and humiliated. Today, no walls can separate |humanitarian or human rights crises in one part of the world from national security crises in another.

- Scientists tell us that the world of nature is so small and interdependent that a butterfly flapping its wings in the Amazon rainforest can generate a violent storm on the other side of the earth. This principle is known as the "Butterfly Effect." Today, we realize, perhaps more than ever, that the world of human activity also has its own "Butterfly Effect" — for better or for worse.

- We have entered the third millennium through a gate of fire. If today, after the horror of 11 September, we see better, and we see further — we will realize that humanity is indivisible. New threats make no distinction between races, nations or regions. A new insecurity has entered every mind, regardless of wealth or status. A deeper awareness of the bonds that bind us all — in pain as in prosperity — has gripped young and old.

- The 20th century was perhaps the deadliest in human history, devastated by innumerable conflicts, untold suffering, and unimaginable crimes.Time after time, a group or a nation inflicted extreme violence on another, often driven by irrational hatred and suspicion, or unbounded arrogance and thirst for power and resources. In response to these cataclysms, the leaders of the world came together at mid-century to unite the nations as never before.

A forum was created — the United Nations — where all nations could join forces to affirm the dignity and worth of every person, and to secure peace and development for all peoples. Here States could unite to strengthen the rule of law, recognize and address the needs of the poor, restrain man’s brutality and greed, conserve the resources and beauty of nature, sustain the equal rights of men and women, and provide for the safety of future generations.

- In the 21st Century I believe the mission of the United Nations will be defined by a new, more profound, awareness of the sanctity and dignity of every human life, regardless of race or religion. This will require us to look beyond the framework of States, and beneath the surface of nations or communities. We must focus, as never before, on improving the conditions of the individual men and women who give the state or nation its richness and character.

- Over the past five years, I have often recalled that the United Nations' Charter begins with the words: "We the peoples." What is not always recognized is that "we the peoples" are made up of individuals whose claims to the most fundamental rights have too often been sacrificed in the supposed interests of the state or the nation.

- A genocide begins with the killing of one man — not for what he has done, but because of who he is. A campaign of 'ethnic cleansing' begins with one neighbour turning on another. Poverty begins when even one child is denied his or her fundamental right to education. What begins with the failure to uphold the dignity of one life, all too often ends with a calamity for entire nations.

In this new century, we must start from the understanding that peace belongs not only to states or peoples, but to each and every member of those communities. The sovereignty of States must no longer be used as a shield for gross violations of human rights. Peace must be made real and tangible in the daily existence of every individual in need. Peace must be sought, above all, because it is the condition for every member of the human family to live a life of dignity and security.

- The rights of the individual are of no less importance to immigrants and minorities in Europe and the Americas than to women in Afghanistan or children in Africa. They are as fundamental to the poor as to the rich; they are as necessary to the security of the developed world as to that of the developing world.

From this vision of the role of the United Nations in the next century flow three key priorities for the future: eradicating poverty, preventing conflict, and promoting democracy. Only in a world that is rid of poverty can all men and women make the most of their abilities. Only where individual rights are respected can differences be channelled politically and resolved peacefully. Only in a democratic environment, based on respect for diversity and dialogue, can individual self-expression and self-government be secured, and freedom of association be upheld.

- I humbly accept the Centennial Nobel Peace Prize. Forty years ago today, the Prize for 1961 was awarded for the first time to a Secretary-General of the United Nations — posthumously, because Dag Hammarskjöld had already given his life for peace in Central Africa. And on the same day, the Prize for 1960 was awarded for the first time to an African — Albert Luthuli, one of the earliest leaders of the struggle against apartheid in South Africa. For me, as a young African beginning his career in the United Nations a few months later, those two men set a standard that I have sought to follow throughout my working life.

- In a world filled with weapons of war and all too often words of war, the Nobel Committee has become a vital agent for peace. Sadly, a prize for peace is a rarity in this world. Most nations have monuments or memorials to war, bronze salutations to heroic battles, archways of triumph. But peace has no parade, no pantheon of victory.

What it does have is the Nobel Prize — a statement of hope and courage with unique resonance and authority. Only by understanding and addressing the needs of individuals for peace, for dignity, and for security can we at the United Nations hope to live up to the honour conferred today, and fulfil the vision of our founders. This is the broad mission of peace that United Nations staff members carry out every day in every part of the world.

- The idea that there is one people in possession of the truth, one answer to the world’s ills, or one solution to humanity’s needs, has done untold harm throughout history — especially in the last century. Today, however, even amidst continuing ethnic conflict around the world, there is a growing understanding that human diversity is both the reality that makes dialogue necessary, and the very basis for that dialogue.

We understand, as never before, that each of us is fully worthy of the respect and dignity essential to our common humanity. We recognize that we are the products of many cultures, traditions and memories; that mutual respect allows us to study and learn from other cultures; and that we gain strength by combining the foreign with the familiar.

- In every great faith and tradition one can find the values of tolerance and mutual understanding. The Qur’a, for example, tells us that "We created you from a single pair of male and female and made you into nations and tribes, that you may know each other." Confucius urged his followers: "when the good way prevails in the state, speak boldly and act boldly. When the state has lost the way, act boldly and speak softly." In the Jewish tradition, the injunction to "love thy neighbour as thyself," is considered to be the very essence of the Torah.

This thought is reflected in the Christian Gospel, which also teaches us to love our enemies and pray for those who wish to persecute us. Hindus are taught that "truth is one, the sages give it various names." And in the Buddhist tradition, individuals are urged to act with compassion in every facet of life.

Each of us has the right to take pride in our particular faith or heritage. But the notion that what is ours is necessarily in conflict with what is theirs is both false and dangerous. It has resulted in endless enmity and conflict, leading men to commit the greatest of crimes in the name of a higher power.

It need not be so. People of different religions and cultures live side by side in almost every part of the world, and most of us have overlapping identities which unite us with very different groups. We can love what we are, without hating what — and who — we are not. We can thrive in our own tradition, even as we learn from others, and come to respect their teachings.

- The lesson of the past century has been that where the dignity of the individual has been trampled or threatened — where citizens have not enjoyed the basic right to choose their government, or the right to change it regularly — conflict has too often followed, with innocent civilians paying the price, in lives cut short and communities destroyed.

The obstacles to democracy have little to do with culture or religion, and much more to do with the desire of those in power to maintain their position at any cost. This is neither a new phenomenon nor one confined to any particular part of the world. People of all cultures value their freedom of choice, and feel the need to have a say in decisions affecting their lives.

- The United Nations, whose membership comprises almost all the States in the world, is founded on the principle of the equal worth of every human being. It is the nearest thing we have to a representative institution that can address the interests of all states, and all peoples. Through this universal, indispensable instrument of human progress, States can serve the interests of their citizens by recognizing common interests and pursuing them in unity.

- This era of global challenges leaves no choice but cooperation at the global level. When States undermine the rule of law and violate the rights of their individual citizens, they become a menace not only to their own people, but also to their neighbours, and indeed the world. What we need today is better governance — legitimate, democratic governance that allows each individual to flourish, and each State to thrive.

- Beneath the surface of states and nations, ideas and language, lies the fate of individual human beings in need. Answering their needs will be the mission of the United Nations in the century to come.

Truman Library address (2006)

[edit]

- In today’s world, the security of every one of us is linked to that of everyone else.

- No nation can make itself secure by seeking supremacy over all others. We all share responsibility for each other’s security, and only by working to make each other secure can we hope to achieve lasting security for ourselves.

— And, I would add that this responsibility is not simply a matter of States being ready to come to each other’s aid when attacked — important though that is. It also includes our shared responsibility to protect populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity — a responsibility solemnly accepted by all nations at last year’s UN world summit. That means that respect for national sovereignty can no longer be used as a shield by Governments intent on massacring their own people, or as an excuse for the rest of us to do nothing when heinous crimes are committed.

- When I look at the murder, rape and starvation to which the people of Darfur are being subjected, I fear that we have not got far beyond “lip service”. The lesson here is that high-sounding doctrines like the “responsibility to protect” will remain pure rhetoric unless and until those with the power to intervene effectively — by exerting political, economic or, in the last resort, military muscle — are prepared to take the lead.

- I believe we have a responsibility not only to our contemporaries but also to future generations — a responsibility to preserve resources that belong to them as well as to us, and without which none of us can survive. That means we must do much more, and urgently, to prevent or slow down climate change. Everyday that we do nothing, or too little, imposes higher costs on our children and our children’s children. Of course, it reminds me of an African proverb — the earth is not ours but something we hold in trust for future generations. I hope my generation will be worthy of that trust.

- We are not only all responsible for each other’s security. We are also, in some measure, responsible for each other’s welfare. Global solidarity is both necessary and possible. — It is necessary because without a measure of solidarity no society can be truly stable, and no one’s prosperity truly secure. That applies to national societies — as all the great industrial democracies learned in the twentieth century — but, it also applies to the increasingly integrated global market economy that we live in today. It is not realistic to think that some people can go on deriving great benefits from globalization while billions of their fellow human beings are left in abject poverty, or even thrown into it. We have to give our fellow citizens, not only within each nation but in the global community, at least a chance to share in our prosperity.

- Both security and development ultimately depend on respect for human rights and the rule of law.

— Although increasingly interdependent, our world continues to be divided — not only by economic differences, but also by religion and culture. That is not in itself a problem. Throughout history, human life has been enriched by diversity, and different communities have learnt from each other. But, if our different communities are to live together in peace we must stress also what unites us: our common humanity, and our shared belief that human dignity and rights should be protected by law.

- Human rights and the rule of law are vital to global security and prosperity. As Truman said, “We must, once and for all, prove by our acts conclusively that Right Has Might”. That’s why this country has historically been in the vanguard of the global human rights movement. But that lead can only be maintained if America remains true to its principles, including in the struggle against terrorism. When it appears to abandon its own ideals and objectives, its friends abroad are naturally troubled and confused.

— And States need to play by the rules towards each other, as well as towards their own citizens. That can sometimes be inconvenient, but ultimately what matters is not inconvenience. It is doing the right thing. No State can make its own actions legitimate in the eyes of others. When power, especially military force, is used, the world will consider it legitimate only when convinced that it is being used for the right purpose — for broadly shared aims –- in accordance with broadly accepted norms.

— No community anywhere suffers from too much rule of law; many do suffer from too little — and the international community is among them. This we must change.

- The US has given the world an example of a democracy in which everyone, including the most powerful, is subject to legal restraint. Its current moment of world supremacy gives it a priceless opportunity to entrench the same principles at the global level.

- Governments must be accountable for their actions in the international arena, as well as in the domestic one.

— Today, the actions of one State can often have a decisive effect on the lives of people in other States. So does it not owe some account to those other States and their citizens, as well as to its own? I believe it does.

— As things stand, accountability between States is highly skewed. Poor and weak countries are easily held to account, because they need foreign assistance. But large and powerful States, whose actions have the greatest impact on others, can be constrained only by their own people, working through their domestic institutions.

— That gives the people and institutions of such powerful States a special responsibility to take account of global views and interests, as well as national ones. And today they need to take into account also the views of what, in UN jargon, we call “non-State actors”. I mean commercial corporations, charities and pressure groups, labor unions, philanthropic foundations, universities and think tanks — all the myriad forms in which people come together voluntarily to think about, or try to change, the world.

— None of these should be allowed to substitute itself for the State, or for the democratic process by which citizens choose their Governments and decide policy. But, they all have the capacity to influence political processes, on the international as well as the national level. States that try to ignore this are hiding their heads in the sand.

- It is only through multilateral institutions that States can hold each other to account. And that makes it very important to organize those institutions in a fair and democratic way, giving the poor and the weak some influence over the actions of the rich and the strong.

- I have continued to press for Security Council reform. But, reform involves two separate issues. One is that new members should be added, on a permanent or long-term basis, to give greater representation to parts of the world which have limited voice today. The other, perhaps even more important, is that all Council members, and especially the major powers who are permanent members, must accept the special responsibility that comes with their privilege. The Security Council is not just another stage on which to act out national interests. It is the management committee, if you will, of our fledgling collective security system.

- My friends, our challenge today is not to save Western civilization — or Eastern, for that matter. All civilization is at stake, and we can save it only if all peoples join together in the task.

You Americans did so much, in the last century, to build an effective multilateral system, with the United Nations at its heart. Do you need it less today, and does it need you less, than 60 years ago?

Surely not. More than ever today, Americans, like the rest of humanity, need a functioning global system through which the world’s peoples can face global challenges together. And in order to function more effectively, the system still cries out for far-sighted American leadership, in the Truman tradition.

I hope and pray that the American leaders of today, and tomorrow, will provide it.

Farewell Speech (2006)

[edit]- Thank you, Senator [Hagel] for that wonderful introduction. It is a great honour to be introduced by such a distinguished legislator.

- And thanks to you, Mr Devine, and all your staff, and to the wonderful UNA chapter of Kansas City, for all you have done to make this occasion possible.

- What a pleasure, and a privilege, to be here in Missouri. It is almost a homecoming for me. Nearly half a century ago I was a student about 400 miles north of here, in Minnesota.

- I arrived there straight from Africa - and I can tell you, Minnesota soon taught me the value of a thick overcoat, a warm scarf and even ear-muffs!

- “If one is going to err, one should err on the side of liberty and freedom.”

- When you leave one home for another, there are always lessons to be learnt'. And I had more to learn when I moved on from Minnesota to the United Nations - the indispensable common house of the entire human family, which has been my main home for the last 44 years.

- Today I want to talk particularly about five lessons I have learnt in the last 10 years, during which I have had the difficult but exhilarating role of Secretary General.

- I think it is especially fitting that I do that here in the house that honours the legacy of Harry S Truman. If FDR [Franklin D Roosevelt] was the architect of the United Nations, President Truman was the master-builder, and the faithful champion of the Organisation in its first years, when it had to face quite different problems from the ones FDR had expected.

- Truman's name will for ever be associated with the memory of far-sighted American leadership in a great global endeavour. And you will see that every one of my five lessons brings me to the conclusion that such leadership is no less sorely needed now than it was 60 years ago.

Quotes about Annan

[edit]- We not only have confidence in him, we support him fully. He is in a very difficult job under very difficult circumstances, but we continue to have hope that he is doing his best. We only want his senior management to exhibit the transparency and accountability that he has proscribed for the organization.

- Rosemarie Waters, president of the United Nations Staff Union [1]

- We in Europe hold Kofi Annan in high esteem and recognise his unstinting efforts in the cause of peace and democracy.

- We are not suggesting or pushing for the resignation of the secretary-general. We have worked well with him in the past and look forward to working with him for some time in the future.

- United States ambassador John Danforth [2]

- Both Bush as well as Tony Blair are undermining an idea [the United Nations]. Is this because the secretary general of the United Nations [Ghanaian Kofi Annan] is now a black man? They never did that when secretary generals were white.

External links

[edit]- Official UN biography

- Nobel Peace Prize biography

- Kofi Annan: Center of the Storm (PBS)

- Kofi Annan: An Online News Hour Focus

- Kofi Annan, President, Global Humanitarian Forum

- Kofi Annan: Profile by Phyllis Bennis of the Global Policy Forum

- "One-on-one with UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan " (October 1998)

- Annan Article in Saga Magazine

- Profile at the Africa Progress Panel

- "U.N. Chief's Record Comes Under Fire" by Colum Lynch, in The Washington Post (24 April 2005)

- "Annan has paid his dues: The UN declaration of a right to protect people from their governments is a millennial change" by Ian Williams, in The Guardian (20 September 2005)

- "Lessons from the U.N. leader" in The Washington Post (12 December 2006)

- "Kofi and U.N. Ideals" in The Wall Street Journal (14 December 2006)

- Statements of Secretary-General Kofi Annan

- Nobel Peace Prize lecture

- In Truman Library speech, Annan says UN remains best tool to achieve key goals of international relations (11 December 2006)

- The Kofi Annan Foundation