W. Claude Jones

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2014) |

William Claude Jones | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 1815 United States |

| Died | March 3, 1884 |

| Occupations | |

William Claude Jones (c. 1815 – March 3, 1884) was an American politician, poet, fabulist, and "pursuer of nubile females,"[1] including several teen brides. Among his accomplishments, he was a member of the Missouri and Arizona Territorial legislatures, United States Attorney for New Mexico Territory, and a member of the Hawaiian privy council.

Missouri

[edit]Details of Jones' birth are uncertain but he appears to have been born around 1815, possibly near Mobile, Alabama.[2] During his lifetime, Jones is known to have given five different locations for his birth including a claim, made while he was living in the New Mexico Territory, that he had been born to an American consul in Catalonia, Spain. There is, however, no record of a U.S. diplomat stationed at any Spanish speaking post around the time of Jones' birth.[3] Details of his education are equally unclear but it is known that he was a highly literate writer.[2] In addition to English, Jones was also fluent and literate in Spanish.[4]

During the Second Seminole War, Jones enlisted as a private in a six-month company from northwestern Missouri.[4][Note 1] He would later claim that he served with a courtesy rank of lieutenant as a commissary officer.[4] His claim was substantiated by an act of the 33rd Congress (S.B. 250) dated July 27, 1854. His service during the war led to his introduction to politics. Beginning in late 1838, Jones served as clerk for a legislative committee established by the Missouri General Assembly designed to look into improper use of troops from the state during the war.[4] After completion of this task, Jones began practicing law in Carrollton, Missouri.[2] He also became a colonel in the local militia, seeing limited service related to the aftermath of the 1838 Mormon War.[4][Note 2]

Jones advanced quickly within the Missouri Democratic party. He became an editor for the Missouri Revised Statutes, secretary for the Missouri State Senate, had a seat on the board of curators for the University of Missouri, and was vice president and legal council for the State Historical Society of Missouri.[4] The 1844 U.S. presidential election also saw him become an elector.[2] While living in Carrollton, Jones met and married Sarah Freeman. The union produced three children: Bennington, Laura, and Claude (died in infancy).[4]

In 1846, Jones moved his family to southwestern Missouri. There he became one of the incorporators for Neosho and won election to a four-year term in the Missouri State Senate.[4] About this time, the nearby Neosho River served as Jones' muse as he penned a poem dealing with two Indian lovers.[4] Jones was not content with his position however and wrote to the President asking for appointment to a federal position. Toward this end he was willing to accept any available position, writing "it matters not" as to the type or location of the appointment.[6] In mid-1847, Jones took his family to Van Buren and Fort Smith, Arkansas where he practiced law for a time. From there he visited Texas, passing through Nacogdoches and Corpus Christi.[6][Note 3] During this time the Missouri legislature was out of session. When Jones returned to Missouri for the beginning of the next session, he discovered that his seat had been declared vacant and a replacement had been elected. Jones challenged the ruling and won back his seat after several days of hearings.[6]

New Mexico

[edit]In 1850, Jones left Missouri for the California Gold Rush.[2] A Missouri newspaper editorialized his wandering spirit, claiming "from California we suppose he will go to Oregon, and from thence to the Sandwich Islands, Tierra del Fuego, Cape Cod or Point-no-Point, and thence perhaps to the Lower Regions."[6] While in California he operated a legal office specializing in Mexican and Spanish land grants while in Benicia, built one of the first wooden buildings in San Jose, and presided as judge during an extra-legal trial in San Luis Obispo.[6] After returning to Missouri in 1853, Jones gave speeches advocating the organization of Nebraska Territory throughout his home state and eastern Kansas.[6]

President Franklin Pierce acted upon Jones' request for federal appointment in August 1854, nominating him to become United States Attorney for New Mexico Territory.[6] Instead of locating in the territorial capital of Santa Fe, Jones placed his office in Las Cruces.[7] His reason for doing so was that El Paso County, Texas was within his district and much of his case load dealt with customs issues for goods coming from El Paso del Norte (now Ciudad Juárez).[8]

Being "acquainted with the Spanish language, and the customs and laws of the country", Jones quickly became "very popular" with the Hispanic population along the Rio Grande.[9] His charming personality also allowed him to quickly make friends among the common folk, friends that often left once they came to know Jones better.[9] Jones had less success winning over the territory's political elite.

A week after his arrival, Jones aggravated many territorial politicians by asking the territorial legislature to memorialize the U.S. Congress by asking for the southern portion of the territory to be divided off and formed into a new territory named "Pimeria" (from the old Spanish name meaning land of the Pimas). After the legislature rejected his request, Jones declared, "The jealousy of New Mexico caused it to sleep the sleep of death."[8] Several months later, Jones accused James Longstreet, "aided by a few desperate individuals", of not paying the import duty on grain imported from Mexico and used by the U.S. Army. While there was probably truth to the accusation, the intended target of the charges was most likely Simeon Hart, an El Paso-based businessman with significant political connections. Jones went so far in the resulting dispute as to write the War department and ask that General John Garland, Longstreet's father-in-law, be removed as commander of the Military Department of New Mexico. The War Department dealt with the letter by forwarding it to Garland.[8]

While he was in New Mexico, Jones' wife, who had remained in Missouri with their children, filed for divorce. After the divorce was finalized, Jones married "a very young Mexican girl" from Mesilla apparently named Maria v. del Refugio. New Mexico's Territorial Delegate to Congress Miguel Antonio Otero, in January 1858, responded to news of the marriage by claiming Jones had "abducted" the supposedly twelve-year-old bride and demanded that President James Buchanan fire the U.S. Attorney. Before any official action could be taken, Jones had submitted his resignation. Jones' second marriage had ended by the time of the 1860 census.[10]

During his time in New Mexico, Jones was a strong proponent of creating a separate territory from the southern portion of New Mexico Territory. When Charles Debrille Poston met him in 1856 the two men organized a petition to the United States Congress supporting the Gadsden Purchase. Additionally, Jones circulated a Spanish language petition for creation of the new territory from the newly squired land. The future "Father of Arizona" later claimed that this petition was the first document he ever saw that used the name "Arizona".[11] After years of petitions without any results, Jones became a proponent of Southern secession in February 1861. He hoped that the Confederate Congress would create the new territory that the U.S. Congress had so far declined to create. Toward this end Jones also announced his candidacy to become Arizona's territorial delegate to the Confederate congress.[12] He also wrote a four-stanza poem praising the stars and bars which was published in the Mesilla Times.[13]

When the American Civil War reached New Mexico Territory in July 1861, Jones was in Santa Fe with battle lines preventing his return to Mesilla.[Note 4] There he was arrested on suspicion of treason but was released several months later when an Albuquerque based grand jury declined to issue an indictment. His imprisonment did however prevent his election to the Confederate Congress. Shifts in the battle lines briefly placed Santa Fe under Confederate control in March 1862. Following the Battle of Glorieta Pass, Jones returned to Mesilla with the retreating Confederate troops from Texas.[13]

From Mesilla, Jones decided to journey to California by way of Chihuahua, Mexico. Bandits stripped him of his possessions and Jones was forced to return to Paso del Norte (now Ciudad Juarez). He remained in the Mexican city, Union officials unwilling to allow the perceived Confederate sympathizer to return to the United States, until President Abraham Lincoln announced his general amnesty plan.[13] Not until February 16, 1864, did Jones take an oath of loyalty in El Paso, Texas.[2]

Arizona Territory

[edit]

After re-entering the United States, Jones moved to Tucson in the newly created Arizona Territory.[14] There he partnered with Colonel George W. Bowie and Captain C. A. Smith, both from the 5th Regiment California Volunteer Infantry, to reopen several mines in the Dragoon Mountains. The filings claimed that Jones had discovered "two ledges of goldbearing quartz" along with silver and copper deposits in June 1856 and had "reopened [them] in 1861 and 1864, but [they] have not been continually worked owing to the hostility of the Apache Indians".[15] This was followed by other partnerships silver mines near Tubac and Mission Los Santos Ángeles de Guevavi. These partnerships appear to have revived Jones' financial health from his loss to Mexican bandits because, on July 6, 1864, he had enough resources to purchase former Sonoran Governor Manuel Gándara's share of the Mission Guevavi mine.[15]

In addition to his financial recovery, Jones experienced an upswing in his political fortunes. In June 1864, he presided over a convention to organize a municipal government in Tucson[2] The next month saw his election to represent Pima County in the 1st Arizona Territorial Legislature.[15] When the legislature convened in Prescott, he was selected to serve as speaker of the House of Representatives[2] During the session, there was a divide between factions wishing to locate the territorial capital in Tucson and others wishing to locate it in Prescott. Jones proposed creation of a new town near the confluence of the Salt and Gila Rivers as a compromise to these positions. He further proposed the new town be named Aztlan after the popular belief at the time that ruins in the area were the product of the Aztec civilization.[15] In recognition of his extensive knowledge, his fellow legislators convinced Jones to give a series of public lectures on the geography, resources, and history of the new territory. They also created the Arizona Historical Society (not the same organization that currently bears that name) and named him to be corresponding secretary.[16] In other actions, Jones translated a condensed version of the territory's new legal code, the "Howell Code", into Spanish.[16][Note 5]

During the session, Jones became romantically involved with Caroline E. Stephens. The fifteen-year-old girl arrived in Prescott with her parents on October 5, 1864, after a six-month journey from Texas.[16] The couple married on November 13, three days after the end of the legislative session, in what has been dubbed the first wedding in Prescott.[2] At the end of the wedding festivities, Jones took his bride to Tucson in the company of Judge Joseph P. Allyn.[16]

Jones was recommended for the position of deputy collector and inspector of customs at Tucson by W. W. Mills, the collector of customs in El Paso, Texas, on March 31, 1865. Jones withdrew his name from consideration on April 3, claiming he would have taken the position if it were located in Wickenburg. He then returned to Prescott with his wife. On May 5, Jones disappeared from Prescott.[16] His abandoned bride received a divorce in April 1867.[2]

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Thompson_Howell

Hawaii

[edit]Details of Jones' life after he abandoned his wife in Prescott are limited for several years. He is known to have traveled by steamship from San Diego to San Francisco, California. During this trip he met another member of the Arizona Territorial Legislature, Edward D. Tuttle, and told him he intended to go to Hawaii.[17]

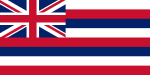

Jones arrived in Honolulu on February 24, 1866 on the American Bark D. C. Murray.[18] On March 6, a mere 11 days after arriving, he swore fealty to the Kingdom of Hawaii and was made a naturalized citizen of the island nation. Six days later, on March 12, he was admitted to the Bar of Hawaii and licensed to practice law. Mark Twain wrote, in his June 22, 1866, letter from Hawai'i, that "Judge Jones" informed him that "he has already more law practice on his hands than he can well attend to." In February 1868, Jones won election to the Legislature of the Kingdom of Hawaii and represented the South Kona district in the House of Representatives. There is no evidence however that Jones had lived in the district at the time of his election. On April 27, 1868, nine days after the legislature convened for its first session, Jones resigned his seat.[19] He resigned because of objections raised by Noble C. R. Bishop, husband of Princess Pau'ahi, as to his right to sit as a representative from South Kona because Jones had not been domiciled in the district prior to his election for the legally required period of three years.

Soon after leaving the legislature, Jones married Ma'ema'e Kailiha'o Meheiwa.[2] The fifteen-year old bride descended from a noble Hawaiian family whose members included Kana'ina-nui, the High Chief who killed Captain Cook in 1779, and Moana-wahine, the ranking High Priestess of Hawai'i Island in the mid 1700s. The union produced sons Bennington, Ulysses and Elias and daughters Aletheia and Minerva before her death in 1881, at age 28, from a smallpox epidemic in Honolulu that eventually killed 287 people, most of them native Hawaiians.[2]

During most of the 1870s, Jones served as a judge. His abilities as a public speaker were also in demand with locals appreciating "his eloquence ... his commanding nose, flashing eyes and marked gestures" and bestowing the sobriquet Aeko (eagle) upon him. This changed in 1880, when Jones met Celso Caesar Moreno. The Italian man had befriended King Kalākaua and convinced the king to name him Prime Minister. Moreno likewise convinced Jones to resign his job as judge and to accept a position on the royal privy council.[19] He accepted the position of Attorney General of Hawaii on August 14, 1880.[20] diplomatic pressure from Britain, France, and the United States prompted the king to abandon his new cabinet.[19] As a result, Jones lost his position as Attorney General on September 27, 1880.[20]

Hard times beset Jones after losing his position as Attorney General. He was unable to find a job capable of replacing the $3000/year income he had received as a judge.[21] He instead served in a lesser position by becoming commissioner of Private Ways and Water Rights at Hilo. Then in early 1881 his fourth wife died at age 28.[22] Jones married a fifth time four months later to Mary Akina. His final marriage lasted till late 1883, when she filed for divorce on grounds of multiple instances of adultery by her husband.[22]

Jones died on March 3, 1884, after a prolonged illness in Wailuku, Maui[2] Hawaiian newspapers published a number of obituaries using information Jones had provided over the years to detail his life before his arrival in the islands. Roughly half of the facts provided by Jones are provably false with another quarter being unverifiable.[3]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Obituaries published in Hawaii at the time of Jones' death incorrectly reported he was commissioned a First Lieutenant.[3]

- ^ Jones would later claim to have served as a colonel commanding a regiment from Alabama in the Mexican–American War during the time he was traveling through Arkansas and Texas.[5]

- ^ Of his time in Texas, Jones claimed to have been "a deputy U.S. Marshal in Texas", and "his name became a terror to the lawless bands of horse thieves and Indians which infested that State ... [he had] a hundred fights with Indians."[3]

- ^ Jones later claimed to have "sided with his compatriots but did not personally join in the struggle, but removed to New Mexico".[3]

- ^ Obituaries published in Hawaii at the time of his death include a claim by Jones that he framed "the first code of laws for the Territory of Arizona".[3]

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Thompson_Howell

Bibliography

[edit]- Finch, L. Boyd (Winter 1990). "William Claude Jones: The Charming Rogue Who Named Arizona". The Journal of Arizona History. 31 (4). Arizona Historical Society: 405–24. JSTOR 41695845.

- Goff, John S. (1996). Arizona Territorial Officials Volume VI: Members of the Legislature A–L. Cave Creek, Arizona: Black Mountain Press. OCLC 36714908.

- Thayer, Wade Warren; Lydecker, Robert Colfax; Hawaii, Supreme Court (1916). A digest of the decisions of the Supreme Court of Hawaii: volumes 1 to 22 inclusive, January 6, 1847 to October 7, 1915. Honolulu: Paradise of the Pacific Press. OCLC 7311302.

External links

[edit]- All about Hawaii. The recognized book of authentic information on Hawaii, combined with Thrum's Hawaiian annual and standard guide ((original from University of Michigan)). Honolulu Star-Bulletin. 1891. pp. 92–97 – via HathiTrust.

- "A List of All the Cabinet Ministers Who Have Held Office in the Hawaiian Kingdom"

- Woods, Roberta. "LibGuides: Hawai'i Legal Research: Attorney General Opinions". law-hawaii.libguides.com.

- Includes a list of Attorneys General for the Kingdom of Hawaii, their salaries and budgets

- ^ Finch 1990, p. 405.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Goff 1996, p. 146.

- ^ a b c d e f Finch 1990, p. 406.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Finch 1990, p. 408.

- ^ Finch 1990, pp. 406, 8.

- ^ a b c d e f g Finch 1990, p. 409.

- ^ Finch 1990, pp. 409–10.

- ^ a b c Finch 1990, p. 410.

- ^ a b Finch 1990, p. 411.

- ^ Finch 1990, pp. 412, 22.

- ^ Finch 1990, pp. 410–11.

- ^ Finch 1990, p. 412.

- ^ a b c Finch 1990, p. 413.

- ^ Finch 1990, pp. 413–14.

- ^ a b c d Finch 1990, p. 414.

- ^ a b c d e Finch 1990, p. 415.

- ^ Finch 1990, p. 417.

- ^ Finch 1990, pp. 417–18.

- ^ a b c Finch 1990, p. 418.

- ^ a b Thayer, Lydecker & Hawaii 1916, p. xv.

- ^ Finch 1990, pp. 418–19.

- ^ a b Finch 1990, p. 419.

- Politicians from Mobile, Alabama

- People of the California Gold Rush

- Members of the Arizona Territorial Legislature

- Members of the Hawaiian Kingdom House of Representatives

- Hawaiian Kingdom judges

- Hawaiian Kingdom attorneys general

- Missouri state senators

- 1810s births

- 1884 deaths

- Arizona pioneers

- 19th-century American legislators

- People from Carrollton, Missouri

- 19th-century Missouri politicians