Transport in the European Union

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2015) |

Transport in the European Union is a shared competence of the Union and its member states. The European Commission includes a Commissioner for Transport, currently Adina Ioana Vălean. Since 2012, the commission also includes a Directorate-General for Mobility and Transport which develops EU policies in the transport sector and manages funding for Trans-European Networks and technological development and innovation, worth €850 million yearly for the period 2000–2006.

During the financial framework 2014–2020 and EU budget 2014, there is 1485.2 euro million commitment for transport, end 761.4 for payment.[1]

Air transport

[edit]Since 1992, year of the inception of the internal market for aviation of the European Union, the number of passengers and routes has increased substantially: from 10,000 daily flights in 1992 to around 25,000 in 2017, and the number of routes from 2,700 to 8,400. In 2017 alone, over 1 billion passengers had flown from, to, or within the European Union.[2] Between 2001 and 2019, European air supply effectively doubled.[3]

The doubling in air supply was accompanied by an increased market share of low-cost carriers within the EU, which went from 5.3% of total seats available in 2001 to 37.3% of the total share in 2019. Most of the increased demand was met in primary airports (i.e. Barcelona, Düsseldorf, Palma de Mallorca), whereas secondary airports which had capitalized on the early rise of low-cost carriers (Brussels-Charleroi, Rome Ciampino, Paris Beauvais) have for the most part fallen in rank.[3]

To combat a fragmented airspace, air control inefficiencies and delays which were costing an estimated $4.2bn as early as 1989, the European Commission introduced plans for a Single European Sky (SES) initiative in 2001, with the purpose of co-ordinating the design, management and regulation of airspace in the Union. The first SES package was adopted in 2004, with subsequent revisions and extensions adopted in 2009 (SES II), 2014 (SES 2+), and 2019 (Amended SES 2+).[4] Five major stakeholders are today involved: the commission is responsible for the implementation of SES; EASA fulfills oversight and support duties for member states, and supports the policymaking of the commission; Eurocontrol is in charge for air traffic flow management and technical support to the commission; and the Single Sky Committee (SSC), composed of representatives of the member states, issues opinions on the implementation work done by the commission. Finally, National Supervisory Authorities (NSAs) are competent with issuing certifications for national airline operators and are entitled to draft and monitor their own performance plans and targets.[5]

The EU also participates in Eurocontrol, which coordinates and plans air traffic control for all of Europe. The European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) has regulatory and executive tasks in the field of civilian aviation safety, such as issuing type certificates.

Water transport

[edit]By 2013, about 74% of the interchange of goods between the European Union and the rest of the world as well as about a 37% of interchange between member states was carried out through its seaports.[6] Maritime transport accounted for about €147 billion in 2013, or 1% of the EU GDP at the time.[7]

The baby steps of a common European port policy were taken in the form of a 1985 memorandum by the EU Commission.[8] It has since, via different white books, alternated bottom-top dynamics of harmonisation with top-bottom dynamics of unification.[9] Vis-à-vis its transport policy, EU have defined operational concepts such as that of the 'motorways of the Sea' and that of 'co-modality'.[9]

As of 2018, the largest ports in EU–28 in terms of shipping volume were Rotterdam, Antwerp, Hamburg, Bremerhaven, Valencia, Piraeus, Algeciras, Felixstowe, Barcelona, Marsaxlokk, Le Havre, Genoa, Gioia Tauro, Southampton and Gdansk.[10]

Established by Regulation (EC) 1406/2002, the European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA) is charged with reducing the risk of maritime accidents, marine pollution from ships and the loss of human lives at sea by helping to enforce the pertinent EU legislation.

Railway transport

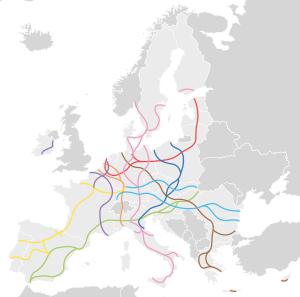

[edit]The European Railway Agency has the mandate to create a competitive European railway area, by increasing cross-border compatibility of national systems, and in parallel ensuring the required level of safety. The ERA sets standards for European railways in the form of ERA Technical Specifications for Interoperability, which apply to the Trans-European Rail network.

The first EU directive for railways requires allowing open access operations on railway lines by companies other than those that own the rail infrastructure. It does not require privatisation, but does require the separation of infrastructure management and operations. The directive has led to reorganisations of many national railway systems.

The EU has also taken the initiative of creating the European Rail Traffic Management System (ERTMS), a single standard for train control and command systems, to enhance cross-border interoperability and the procurement of signalling equipment.

The EU 28 had:

- 8 952 kilometres of High Speed Rail Network at end of year 2018, with 1686 kilometres of lineunder construction

- 217 236 kilometres of lines in use including 117 348 kilometres of electrified lines in 2017

Over the 2006–2019 period, railway freight transport peaked in EU–27 in 2007, with 416 billion tonne-kilometres.[11] The targets of the European Green Deal contemplate a forceful shift from road to rail freight transport, which is underrepresented as of 2020.[12]

In May 2022, some countries in the European Union strongly reduced the price for traveling on Public transport, among others, because this is a relatively climate-friendly mode of transportation: Germany, Austria, Ireland (country), Italy. Germany reduced the price to 9 euro. In some cities the price was cut by more than 90%. The national rail company of Germany committed to increase the number of trains and extend lines to new destinations. The use of trains significantly increased so that "ticket websites have crashed upon the release of the tickets."[13][14]

Road transport

[edit]In 2012, the EU-28 had a network of 5 000 000 kilometres of paved road – compared to 5258 thousands for the US and 3610 thousands for China – including 73 200 kilometres of motorways – compared to 92 thousands for the US and 96.2 thousands for China.[15]

National policies

[edit]Germany, Spain and France possess the most extensive network of motorways exceeding 10,000 km each. This figure is more than double to any other European country. Similarly, their rail infrastructure surpasses 15,000 km.[16][17] The total investment reached €6 billion for Spain and nearly double the amount for Germany and France.[16] In terms of their population and territorial extension the Netherlands and Belgium have a better coverage and higher investment per square kilometre.[16]

EU policies

[edit]Road freight transport makes 73% of all inland freight transport activities in the EU in 2010.[18]

Aim of the EU is to provided efficient, safe, secure and environmentally friendly land transport.[19]

According to Union guidelines for the development of the trans-European transport network,[20] "high-quality roads shall be specially designed and built for motor traffic, and shall be either motorways, express roads or conventional strategic roads."

EU laws include:

- access to the profession: Regulation (EC) No 1071/2009[21] In 2011, 138,454 million tonnes kilometres was transported as international trade.[22]

- driving working time: Directive 2002/15/EC and Regulation (EC) 561/2006: 9 hours daily driving period; weekly driving time may not exceed 56 hours; Daily rest period shall be at least 11 hours[23]

- "smart" tachographs, required under Regulation (EU) 165/2014. "Smart" tachographs use technology to avoids unnecessary vehicle stops for checking[24]

- common rules on distance-related tolls and time-based user charges (vignettes) for heavy goods vehicles (above 3.5 tonnes) for the use of certain infrastructures is defined in Directive 2011/76/EU[25]

Motorways and Express road

[edit]For some topics, law applicable for roads is based on European directives and some international treaties such as European Agreement on Main International Traffic Arteries of 15 November 1975.

In European Union, a road can be considered as a "motorway" or also as an "express road".

In European union, the notion of express road is slightly less strict than the notion of motorway; according to the definition, "an express road is a road designed for motor traffic, which is accessible primarily from interchanges or controlled junctions and which prohibits stopping and parking on the running carriageway; and does not cross at grade with any railway or tramway track."

According to the CJEU, an environmental impact assessment should be performed on motorways, express roads and «construction of a new road of four or more lanes, or realignment and/or widening of an existing road of two lanes or less so as to provide four or more lanes, where such new road, or realigned and/or widened section of road would be 10 km or more in a continuous length».[26]

Another position of the CJEU confirmed the first one and considers that an urban road around a city can be considered as an express road even if those roads do not form part of the network of main international traffic arteries or are located in urban areas when it matches with its definition provided in point II.3 of Annex II to the European Agreement on Main International Traffic Arteries (AGR), signed in Geneva on 15 November 1975.[27]

Safety

[edit]Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Between 2001 and 2010, the number of road deaths in the EU decreased by 43%, and between 2010 and 2018 by another 21%. However, 25,100 people still died on EU roads in 2018 and about 135,000 were seriously injured.

The yearly cost of road crashes in the EU has been estimated to be around €280 billion or 2% of the GDP.

Safety plan

[edit]The Commission decided to base its road safety policy framework for the decade 2021 to 2030 on the Safe System approach.

For coordination, Europe has a "European Coordinator for road safety and related aspects of sustainable mobility".[28]

| Indicator | Definition |

|---|---|

| Speed | Percentage of vehicles traveling within the speed limit |

| Safety belt | Percentage of vehicle occupants using the safety belt or child restraint system correctly |

| Protective equipment | Percentage of riders of powered two wheelers and bicycles wearing a protective helmet |

| Alcohol | Percentage of drivers driving within the legal limit for blood alcohol content (BAC) |

| Distraction | Percentage of drivers NOT using a handheld mobile device |

| Vehicle safety | Percentage of new passenger cars with a Euro NCAP safety rating equal or above a predefined threshold |

| Infrastructure | Percentage of distance driven over roads with a safety rating above an agreed threshold |

| Post-crash care | Time elapsed in minutes and seconds between the emergency call following a collision resulting in personal injury and the arrival at the scene of the collision of the emergency services |

Space

[edit]This article needs to be updated. (July 2016) |

The EU currently cooperates with the European Space Agency, which is expected to become an EU agency in 2020. One of their projects is the satellite navigation system Galileo.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Multiannual financial framework 2014-2020 and EU budget 2014 : The figures. Publications Office of the European Union. 5 February 2014. ISBN 9789279343483.

- ^ REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS Aviation Strategy for Europe: Maintaining and promoting high social standards

- ^ a b Jimenez, Edgar; Suau-Sanchez, Pere (2020). "Reinterpreting the role of primary and secondary airports in low-cost carrier expansion in Europe". Journal of Transport Geography. 88: 102847. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102847. PMC 7445473. PMID 32863620.

- ^ European Court of Auditors (2017). "Single European Sky: a changed culture but not a single sky" (Special report no. 17): 14–15.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ European Court of Auditors (2017). "Single European Sky: a changed culture but not a single sky" (Special report no. 17): 13–14.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Ports 2030. Gateways for the Trans European Transport Network" (PDF). Directorate-General for Mobility and Transport. September 2013. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 December 2015.

- ^ González-Laxe 2020, p. 4.

- ^ González-Laxe, Fernando (2020). "European Port Policy: The new challenges of governance". Revista Galega de Economía. 29 (1). Santiago de Compostela: Universidad de Santiago de Compostela: 1–17. doi:10.15304/rge.29.1.6401. hdl:2183/25837. S2CID 219414109.

- ^ a b González-Laxe 2020, p. 3.

- ^ González-Laxe 2020, p. 10.

- ^ "Railway freight transport statistics". Eurostat. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Preindl, Raphael; Stölzle, Wolfgang (May 2021). "Combined transport in light of the European Green Deal".

- ^ Klinkenberg, Abby. "Public Transit Prices Slashed Across Europe". Fair Planet. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ Andrei, Mihai (3 June 2022). "Germany slashes public transit fares to reduce fuel usage". ZME Science. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ "EU transport in figures – Statistical Pocketbook 2015" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d European railways and motorways infrastructure (2013), http://hypowebsis.blogspot.de/2013/10/european-railway-and-motorway.html, with data from BBSR, BBR, Germany.

- ^ "europa road". europa. 23 November 2018.

- ^ "Road Freight Transport Vademecum 2010 Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 January 2017.

- ^ "Road". European Commission. 22 September 2016.

- ^ Regulation (EU) No 1315/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council

- ^ "Rules governing access to the profession". 22 September 2016.

- ^ "Report on the State of the EU Road Haulage Market" (PDF). 25 February 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 December 2018.

- ^ "Driving time and rest periods". 22 September 2016.

- ^ "Tachograph". European Commission. 22 September 2016.

- ^ "Road Infrastructure Charging – Heavy Goods Vehicles". 22 September 2016.

- ^ Case C‑142/07, Ecologistas en Acción-CODA v Ayuntamiento de Madrid, http://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf?docid=68146&doclang=EN

- ^ Judgment of the Court (Sixth Chamber) of 24 November 2016. Bund Naturschutz in Bayern e.V. and Harald Wilde v Freistaat Bayern, ECLI:EU:C:2016:898

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 June 2019. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)