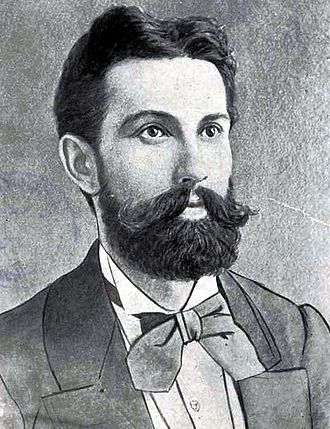

Nicolae Densușianu

Nicolae Densușianu (Romanian pronunciation: [nikoˈla.e densuʃiˈanu]; 18 April 1846 – 24 March 1911) was a Romanian ethnologist and collector of Romanian folklore. He was a corresponding member of the Romanian Academy, with a specialty in history.[1] His main work, for which he is chiefly remembered, was the posthumously printed Dacia Preistorică (1913), with a preface contributed by C. I. Istrati; a facsimile edition was published in 2002 by Editura Arhetip, Bucharest.[1] In Dacia Preistorică Densușianu combined the studies of folklore and comparative religion with archaeology to construct a theory about the Prehistoric cultures of Dacia. The work has drawn criticism for unprofessionalism and evidence of nationalism, and for standing at the source of Dacianism.[2] Mainstream scholars regarded his book as fanciful and unscientific.

His works hypothesize the existence of a Dacian-centered "Pelasgian Empire", created in the 6th millennium BC, and which, he claimed, was governed by Uranus and Saturn and comprised all of Europe.[3] Densușianu, who believed that Latin was a dialect of Dacian, also argued that the Dacians migrated to the Italian Peninsula in the Antiquity, where they laid the foundations of Ancient Rome.[3]

Biography

[edit]Born in the village of Densuș, in Transylvania, which at that time was part of Austria-Hungary, he was raised in a Romanian cultural environment. Around 1867, he met the adolescent Moldavian-born Romanian Mihai Eminescu, later known as a major poet, who had fled his father's home and was traveling aimlessly throughout Transylvania.[4] Densușianu and Eminescu were acquainted in Sibiu, where the latter was living in extreme poverty.[4] Soon after, Eminescu crossed the Southern Carpathians and settled in the Old Kingdom.[4]

Having received his law degree from the University of Sibiu (1872), he practiced law at Făgăraș, then Brașov, then in other parts of the region. In 1877, at the beginning of the Russo-Turkish War, he returned to Romania and received citizenship in the newly independent state. In Bucharest, attached to the Court of Appeal, Densușianu became involved with the nationalistic movement in favor of a Greater Romania. He published — in French, for a wider audience — L'element Latin en orient. Les Roumains du Sud: Macedoine, Thessalie, Epire, Thrace, Albanie, avec une carte ethnographique ("The Latin element in the east. The Romanians of the South: Macedonia, Thessaly, Epirus, Thrace, Albania, with an ethnographic map").

In 1878 he received a commission from the Romanian Academy to research and collect historical documents in the libraries and archives of the Hungarian Kingdom (Budapest) and in Transylvania at Cluj, Alba Iulia and Brașov. Over fifteen months, he discovered hundreds of original documents, manuscripts, chronicles, treaties, manifestos, old drawings, paintings and facsimiles. For his contribution, he was elected in 1880 to a corresponding membership and the position of librarian archivist. In 1884 he received the position of translator for the Romanian Army General Staff and published The revolution of Horia in Transylvania and Hungary, 1784-1785, written on the basis of 783 official documents; its sale was banned in Hungary, due to its nationalist content. Among others, the book composed a historical tradition linking the rebel leader Vasile Ursu Nicola with Dacian prehistory.[5]

In 1885 his Monuments for the history of the country of Fogaras compared the ancient history of the Romanians of Transylvania to their repressed situation under Austro-Hungarian rule.

Densușianu, who was planning to start researching his Dacia Preistorică, and, to this end, left for Italy in 1887. Along the route, he visited the Academy of Agram, where he studied manuscripts regarding the Vlach population settled in the valley of the Kupa (in present-day Croatia); in Istria, he collected material in local villages where the Istro-Romanian language was spoken. At Dubrovnik in Dalmatia, he studied the archives of the Ragusan Republic. After reaching Italy, he spent seven months in the Vatican Archives and traveled through the Mezzogiorno before returning home.

Between 1887 and 1897 six volumes appeared of his Documents regarding the History of Romanians, 1199-1345, and in 1893 he wrote the study The religious independence of the Romanian Metropolitan Church of Alba-Iulia. He also contributed a collection of folklore (Vechi cîntece și tradiții populare românești: texte poetice din răspunsurile la "Chestionarul istoric", published in 1893–1897). In 1894, he retired to finish his large-scale work.

In 1902, Nicolae Densușianu was named a corresponding member of the Romanian Geographical Society. Two years later, he published a study about the development of the Romanian language, which, he claimed, traced its origins back to prehistorical times. Articles on Romanian military history appeared sporadically during the long years he spent readying his major work for the printer. It was almost complete at the time of his death.

Assessments and legacy

[edit]Densușianu was the target of much criticism for his approach to Romanian history and to the science of history in general. Among his earliest critics was Titu Maiorescu, leader of the conservative literary society known as Junimea, who strongly reacted against amateurism and Romantic nationalist discourse in the works of Romanian intellectuals of his day. In 1893, writing to geographer Simion Mehedinți, Maiorescu spoke against what he defined as "phantasmagoria" in the works of Densușianu, Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu, and Alexandru Dimitrie Xenopol.[6]

Part of Densușianu's thesis was adopted by several official historians during the late years of Nicolae Ceaușescu's communist regime, serving as inspiration for a new discourse, one autarkic and nationalist in tone.[7]

Vasile Pârvan stated: "Nicolae Densusianu wrote his fantastic novel Prehistoric Dacia, full of mythology and absurd philology, which at its appearance (posthumously: 1913) aroused an admiration and a boundless enthusiasm among lay Romanians for archaeology".[8][9] Alexandru D. Xenopol stated: "The theory of this author that Dacians would have coagulated the first civilization of the humankind shows that we deal with a product of chauvinism, not with a product of science".[9] In other words, Pârvan and Xenopol have rejected his book "as a dilettantish and chauvinist fantasy".[10] Nicolae Iorga chastised him "for his 'more than odd' hypotheses."[11]

Eugen Ciurtin stated "a minimal contact with the bibliography of the subject leaves one hopeless: nobody reads him any longer" (meaning no serious scholar has written peer-reviewed articles about Densușianu's Dacia Preistorică for a long time).[12] Others have stated "Densusianu's fancy was too bold which made the historians ignore him".[13] Dan Alexe stated that the book is "mystical delirium",[14] and called its author "an occultist notary without schooling in history and linguistics"[15] and "a clinical case of self-delusion".[14] Florin Țurcanu stated about Densușianu: "tireless creator of phantasmagorias".[16][17]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b "Dacia Preistorica, Nicolae Densusianu, Editura Arhetip (2002)".

- ^ Boia, p.147-149, 353-354

- ^ a b Boia, p.148

- ^ a b c Tudor Vianu, Scriitori români, Vol. II, Editura Minerva, Bucharest, 1970, p.139-140. OCLC 7431692

- ^ Boia, p.147-148

- ^ Z. Ornea, Junimea şi junimismul, Vol. II, Editura Minerva, Bucharest, 1998, p.299-300. ISBN 973-21-0562-3

- ^ Boia, p.156-157

- ^ Steven A. Krebs (2000). Settlement in Classical Dobrogea. Indiana University. p. 32.

- ^ a b Mircea Babeș, "Renașterea Daciei?", Observatorul Cultural, 9 September 2003.

- ^ Tchavdar Marinov (13 March 2015). "Ancient Thrace in the Modern Imagination: Ideological Aspect of the Construction of Thracian Studies in Southeast Europe (Romania, Greece, Bulgaria)". In Roumen Daskalov; Alexander Vezenkov (eds.). Entangled Histories of the Balkans - Volume Three: Shared Pasts, Disputed Legacies. BRILL. p. 31. ISBN 978-90-04-29036-5.

- ^ Densușianu, N.; Oprișan, I. (1975). Vechi cîntece și tradiții populare românești: texte poetice din răspunsurile la "Chestionarul istoric" (1893-1897). Ediţii critice de folclor (in Romanian). Minerva. Retrieved 2018-10-30.

- ^ Ciurtin (2004)

- ^ Rumanian Review. Europolis Pub. 1987. p. 153.

- ^ a b Dan Alexe (2015). Dacopatia și alte rătăciri românești. Humanitas SA. p. 95. ISBN 978-973-50-4978-2.

- ^ Alexe (2015: 94)

- ^ Florin Țurcanu (21 December 2007). "Intalnire cu doi istorici ai religiilor". Revista 22 (in Romanian). Archived from the original on 31 October 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ^ Andrei Oișteanu (2016). Religie, politică și mit. Texte despre Mircea Eliade și Ioan Petru Culianu. Serie de autor (in Romanian). Polirom. p. 477. ISBN 978-973-46-5060-6. Retrieved 2018-10-30.

References

[edit]- Lucian Boia, Istorie şi mit în conştiinţa românească, Humanitas, Bucharest, 1997

- (in Romanian) Eugen Ciurtin, "Dacia, tot mai preistorică", Observatorul Cultural, 9 April 2002, an article critical of Densușianu's aims and methods Archived 26 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

External links

[edit]- 1846 births

- 1911 deaths

- People from Hunedoara County

- Emigrants from Austria-Hungary to Romania

- Romanian Austro-Hungarians

- Essayists from Austria-Hungary

- Romanian folklorists

- Romanian Greek-Catholics

- Romanian writers in French

- Writers from Austria-Hungary

- Historiography of Dacia

- 20th-century Romanian translators

- 19th-century Romanian translators

- 19th-century essayists

- 20th-century Romanian essayists