Dogville

| Dogville | |

|---|---|

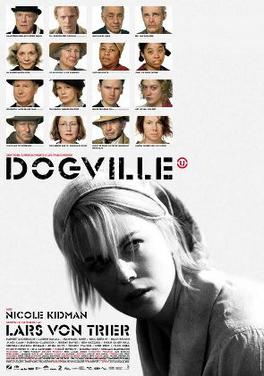

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Lars von Trier |

| Written by | Lars von Trier |

| Produced by | Vibeke Windeløv |

| Starring | |

| Narrated by | John Hurt |

| Cinematography | Anthony Dod Mantle |

| Edited by | Molly Marlene Stensgård |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 178 minutes[5] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $10 million[6] |

| Box office | $16.7 million[6] |

Dogville is a 2003 avant-garde thriller[7][8] film written and directed by Lars von Trier, and starring an ensemble cast led by Nicole Kidman, Lauren Bacall, Paul Bettany, Chloë Sevigny, Stellan Skarsgård, Udo Kier, Ben Gazzara, Patricia Clarkson, Harriet Andersson, and James Caan with John Hurt narrating. It is a parable that uses an extremely minimal, stage-like set to tell the story of Grace Mulligan (Kidman), a woman hiding from mobsters, who arrives in the small mountain town of Dogville, Colorado, and is provided refuge in return for physical labor.

The film is the first in von Trier's incomplete USA – Land of Opportunities trilogy, which was followed by Manderlay (2005) and is projected to be completed with Washington. The film was in competition for the Palme d'Or at the 2003 Cannes Film Festival.[9] It was screened at various film festivals before receiving a limited release in the US on March 26, 2004.

Dogville opened to polarized reviews from critics. Some considered it to be pretentious or exasperating; it was viewed by others as a masterpiece,[10] and has widely grown in stature since its initial release. It was later included in the 2016 poll of the greatest films since 2000 conducted by BBC. Filmmakers such as Quentin Tarantino and Denis Villeneuve have praised the film.[11]

Plot structure

[edit]The story of Dogville is told in nine chapters and a prologue, with a one-sentence description of each chapter given in the film, in the vein of such chapter headings in many 19th-century novels. These descriptions are given below.

Prologue

[edit]- Which introduces us to the town and its residents

Dogville is a very small American town by an abandoned silver mine in the Rocky Mountains, with a road leading up to it and nowhere else to go but the mountains. The film begins with a prologue in which a dozen or so of the fifteen citizens are introduced. They are portrayed as lovable, good people with small flaws which are easy to forgive.

The town is seen from the point of view of Tom Edison Jr., an aspiring writer and philosopher who procrastinates by trying to get his fellow citizens together for regular meetings on the subject of "moral rearmament". It is clear that Tom wants to succeed his aging father, a physician, as the moral and spiritual leader of the town.

Chapter 1

[edit]- In which Tom hears gunfire and meets Grace

It is Tom who first meets Grace Mulligan, who is on the run from gangsters who presumably shot at her. Grace wishes to keep running, but Tom assures her that the mountains ahead are too difficult to pass. As they talk, the gangsters approach the town, and Tom quickly hides Grace in the nearby mine. One of the gangsters asks Tom if he has seen the woman, which he denies. The gangster then offers him a reward and hands him a card with a phone number to call in case Grace shows up.

Tom decides to use Grace as an "illustration" in his next meeting—a way for the townspeople to prove that they are indeed committed to community values, can receive a gift, and are willing to help the stranger. They remain skeptical, so Tom proposes that Grace should be given a chance to prove that she is a good person. Grace is accepted for two weeks in which, as Tom explains to her after the meeting, she must gain the friendship and trust of the townspeople.

Chapter 2

[edit]- In which Grace follows Tom's plan and embarks upon physical labor

On Tom's suggestion, Grace offers to do chores for the citizens—talking to the lonely, blind Jack McKay, helping to run the small shop, looking after the children of Chuck and Vera, and so forth. After some initial reluctance, the people accept her help in doing those chores that "nobody really needs" but which nevertheless make their lives easier. As a result, she becomes an accepted part of the community.

Chapter 3

[edit]- In which Grace indulges in a shady piece of provocation

Grace begins to make friends, including Jack, who pretends that he is not blind. She earns his respect upon tricking him into admitting that he is blind. Once the two weeks are over, everyone votes at the town meeting that Grace should be allowed to stay.

Chapter 4

[edit]- Happy times in Dogville

In tacit agreement Grace is expected to continue her chores, which she does gladly, and is even paid small wages which she saves up to purchase a set of seven expensive porcelain figurines, one at a time, from Ma Ginger's shop. Things go well in Dogville until the police arrive to place a "Missing" poster featuring Grace's picture and name on the mission house. With the townspeople divided as to whether they should cooperate with the police, the mood of the community darkens somewhat.

Chapter 5

[edit]- Fourth of July after all

Still, things continue as usual until the 4th of July celebrations. After Tom awkwardly admits his love to Grace which she reciprocates and the whole town expresses their agreement that it has become a better place thanks to her, the police arrive again to replace the "Missing" poster with a "Wanted" poster. Grace is now wanted for participation in a bank robbery. Everyone agrees that she must be innocent, since at the time the robbery took place, she was doing chores for the townspeople every day.

Nevertheless, Tom argues that because of the increased risk to the town now that they are harboring someone who is wanted as a criminal, Grace should provide a quid pro quo and do more chores for the townspeople within the same time, for less pay. At this point, what was previously a voluntary arrangement takes on a slightly coercive nature as Grace is clearly uncomfortable with the idea. Still, being very amenable and wanting to please Tom, Grace agrees.

Chapter 6

[edit]- In which Dogville bares its teeth

At this point the situation worsens, as with her additional workload, Grace inevitably makes mistakes, and the people she works for seem to be equally irritated by the new schedule—and take it out on Grace. The situation slowly escalates, with the male citizens making small advances to Grace and the females becoming increasingly critical and abusive. Even the children are perverse: Jason, the 10-year-old son of Chuck and Vera, asks Grace to spank him, until she finally complies after much provocation (von Trier has noted that this is the first point in the film where it is clear how completely Grace's lack of social status and choices makes her vulnerable to other people manipulating her).[12] The hostility towards Grace finally reaches a turning point as well when Chuck rapes her in his home.

Chapter 7

[edit]- In which Grace finally gets enough of Dogville, leaves the town, and again sees the light of day

That evening, Grace tells Tom what happened and he starts to form a plan for her escape. The next day, Vera confronts Grace for spanking her son Jason and Liz informs her that a few people saw Tom leave her shack very late the night before, casting suspicions on her virtue. The next evening, she is confronted again by Vera, Liz and Martha in her shack. Martha witnessed a sexual encounter between Chuck and her in the apple orchard. Vera blames her for seducing her husband and decides to punish Grace by destroying the figurines. Grace begs her to spare them and tries to remind Vera of all the good things she has done for her including teaching her children the philosophy of stoicism. Vera cruelly uses it against her while destroying the figurines she worked hard for, claiming that she will stop smashing them if Grace refrains from crying. Grace goes to Tom that evening and they decide to bribe the freight truck driver Ben to smuggle her out of town in his truck. En route, she is raped by Ben, after which he returns Grace to Dogville.

The town agrees that they must not let her escape again. The money paid to Ben to help Grace escape had been stolen by Tom from his father—but when Grace is blamed for the theft, Tom refuses to admit he did it because, as he explains, this is the only way he can still protect Grace without people getting suspicious. So, Grace finally becomes a slave: she is chained, repeatedly raped, and abused by the people of the town. She is also humiliated by the children who ring the church bell every time she is violated, much to Tom's disgust.

Chapter 8

[edit]- In which there is a meeting where the truth is told and Tom leaves (only to return later)

This culminates in a late-night general assembly in which Grace—following Tom's suggestion—relates calmly all that she has endured from everyone in town, then heads back to her shack. Embarrassed and in complete denial, the townspeople finally decide to turn her over to the mobsters—assuming that Grace will be executed. As Tom tells Grace this, declaring his allegiance to her over the town, he attempts to make love to her. Still chained, she responds to his advances by saying "it would be so beautiful, but from the point of view of our love so completely wrong. We were to meet in freedom."[13] She questions if thoughts of using force against her are in fact why he is so upset, noting that he could have her if he wants—all he needs to do is threaten her to get his way, as the others have done. Tom defends his intentions as pure, but upon reflection realizes that what she says is true. Shaken by self-doubt, he decides it would jeopardize his career as a philosopher if this doubt were allowed to grow. To rid himself of its source, he decides to personally call the mobsters and turn Grace over. Grace, exhausted and faced with yet another bed to make, sees no end to the mundane drudgery of her position in Dogville. She is surprised when she mutters to herself, "Nobody's gonna sleep here."[13] Her "ominous" words echo those of Pirate Jenny and foreshadow doom in Dogville.

Chapter 9 and ending

[edit]- In which Dogville receives the long-awaited visit and the film ends

When the mobsters finally arrive, they are welcomed cordially by Tom and an impromptu committee of other townspeople. Grace is then freed by the indignant henchmen, and her true identity is revealed: she is the daughter of a powerful gang leader who ran away because she could not stand his dirty work. Her father motions her into his Cadillac and argues with her about issues of morality. After some introspection, Grace reverses herself and comes to the conclusion that Dogville's crimes cannot be excused due to the difficulty of their circumstances. Tom, who has become aware that the mobsters pose a threat to himself and the town, is momentarily remorseful, but rapidly descends into rationalization for his actions. Grace sadly returns to her father's car, accepts his power, and uses it to command that Dogville be removed from the earth.

Grace tells the gangsters to make Vera watch her children die, one by one, as punishment for destroying her figurines. She instructs them only to stop killing the children if Vera can refrain from crying, stating that she "owes her that". Dogville is burned to the ground and all of its inhabitants brutally massacred with the exception of Tom, whom she executes personally with a revolver right after he applauds the effectiveness of her use of illustration as an attempt to get her to spare him. After the massacre, the gangsters hear a barking sound from Chuck and Vera's house. It is the dog Moses. A gangster aims a gun at the dog, but Grace commands that he should live: "He's just angry because I once took his bone." The chalk drawing of Moses becomes a real dog as his barks lead into the credits. The credits show a series of documentary photos of poverty-stricken Americans from Jacob Holdt's American Pictures (1984), accompanied by the song "Young Americans" by David Bowie.

Cast

[edit]- John Hurt as Narrator

- Nicole Kidman as Grace Margaret Mulligan

- Lauren Bacall as Ma Ginger

- Paul Bettany as Tom Edison, Jr.

- Chloë Sevigny as Liz Henson

- Stellan Skarsgård as Chuck

- Jean-Marc Barr as The Man with the Big Hat

- Udo Kier as The Man in the Coat

- Ben Gazzara as Jack McKay

- James Caan as The Big Man

- Patricia Clarkson as Vera

- Shauna Shim as June

- Bill Raymond as Mr. Henson

- Jeremy Davies as Bill Henson

- Philip Baker Hall as Tom Edison, Sr.

- Blair Brown as Mrs. Henson

- Željko Ivanek as Ben

- Harriet Andersson as Gloria

- Siobhan Fallon Hogan as Martha

- Cleo King as Olivia

- Miles Purinton as Jason

Pilot

[edit]Dogville: The Pilot was shot during 2001 in the pre-production phase to test whether the concept of chalk lines and sparse scenery would work. The 15-minute pilot film starred Danish actors Sidse Babett Knudsen (as Grace) and Nikolaj Lie Kaas (as Tom). Eventually Lars von Trier was happy with the overall results. Thus, he and the producers decided to move forward with the production of the feature film. The test pilot was never shown in public, but is featured on the second disc of the Dogville (2003) DVD, released in November 2003.[14]

Staging

[edit]The story of Dogville is narrated by John Hurt in nine chapters and takes place on a stage with minimalist scenery. Some walls and furniture are placed on the stage, but the rest of the scenery exists merely as white painted outlines which have big labels on them; for example, the outlines of gooseberry bushes have the text "Gooseberry Bushes" written next to them. While this form of staging is common in black box theaters, it has rarely been attempted on film before—the Western musical Red Garters (1954) and Vanya on 42nd Street (1994) being notable exceptions. The bare staging serves to focus the audience's attention on the acting and storytelling, and also reminds them of the film's artificiality. As such it is heavily influenced by the theatre of Bertolt Brecht. (There are also similarities between the song "Seeräuberjenny" ("Pirate Jenny") in Brecht and Kurt Weill's Die Dreigroschenoper (The Threepenny Opera) and the story of Dogville.[15] Chico Buarque's version of this song, "Geni e o Zepelim" [Geni and the Zeppelin], deals with the more erotic aspects of abjection and bears striking similarity to von Trier's cinematic homage to the song.) The film used carefully designed lighting to suggest natural effects such as the moving shadows of clouds, and sound effects are used to create the presence of non-existent set pieces (e.g., there are no doors, but the doors can always be heard when an actor "opens" or "closes" one).

The film was shot on high-definition video using a Sony HDW-F900 camera in a studio in Trollhättan, Sweden.

Interpretations

[edit]According to von Trier, the point of the film is that "evil can arise anywhere, as long as the situation is right".[16]

Film review show At the Movies with Ebert & Roeper criticized Dogville as having a strongly anti-American message, citing, for example, the closing credits sequence with images of poverty-stricken Americans which were taken from Jacob Holdt's documentary book American Pictures (1984), and accompanied by David Bowie's song "Young Americans".[17]

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]Dogville polarised critics upon its United States theatrical release, with Metacritic giving it a score of 61 ("Generally favourable reviews")[18] and the Rotten Tomatoes critics' consensus for it stating simply, "A challenging piece of experimental filmmaking."[19] 70% of critics gave the film a positive review, with an average score of 7/10, based on 168 reviews.[19] Many hailed it as an innovative and powerful artistic statement,[20] while others considered it to be an emotionally detached or even misanthropic work. In The Village Voice, J. Hoberman wrote, "For passion, originality, and sustained chutzpah, this austere allegory of failed Christian charity and Old Testament payback is von Trier's strongest movie—a masterpiece, in fact."[21] Peter Travers of Rolling Stone gave the film 3.5/4 stars, praising Kidman's performance and dubbing it "a movie that never met a cliche it didn't stomp on."[22] Scott Foundas of LA Weekly described it as a work of "boldness, cutting insight, [and] intermittent hilarity", and interpreted it as "a potent parable of human suffering."[23] In Empire, Alan Morrison wrote that "Dogville, in a didactic and politicised stage tradition, is a great play that shows a deep understanding of human beings as they really are."[24]

In the Los Angeles Times, on the other hand, Manohla Dargis dismissed it as "three hours of tedious experimentation."[25] Richard Corliss of Time argued that von Trier lacked humanity and wrote that the director "presumably wants us to attend to his characters' yearnings and prejudices without the distractions of period furnishings. It's a brilliant idea, for about 10 minutes. Then the bare set is elbowed out of a viewer's mind by the threadbare plot and characterizations."[26] Roger Ebert, who gave it two out of four stars, felt that the film was so pedantic as to make von Trier comparable to a crank, and viewed it as "a demonstration of how a good idea can go wrong."[27] In the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Sean Axmaker said, "There's no denying von Trier is visually intriguing. ... But as an artist, his contempt for humanity is becoming harder to hide with stylistic flourish."[28] Charles Taylor of Salon additionally responded to allegations of the film's anti-Americanism with the charge that it was "anti-human", and said that it was "as total a misanthropic vision as anything control freak Stanley Kubrick ever turned out"—while personally admitting that he felt von Trier was as deliberate a filmmaker as Kubrick.[29]

Later, Dogville was named one of the greatest films of its decade in The Guardian,[30] The List,[31] and Paste.[32] In 2016, it was ranked one of the 100 greatest motion pictures in a critics' poll conducted by BBC Culture.[33] It was listed the 37th best film of the same time period by The Guardian critics.[34]

American director and screenwriter Quentin Tarantino has named the film as one of the 20 best to have been released during the time of his active career as a director; (which was between 1992 and 2009 when he was interviewed)[35] he said that if it had been written for the stage, von Trier would have won a Pulitzer Prize.[36]

Box office

[edit]The film grossed $1,535,286 in the US market and $15,145,550 from the rest of the world for a total gross of $16,680,836 worldwide. In the opening US weekend it did poorly, grossing only $88,855. The movie was released in only nine theaters, with an average of $9,872 per theater.[6] In Denmark, the film grossed $1,231,984.[37] The highest-grossing country was Italy, with $3,272,119.[37]

"Best-of" lists

[edit]Dogville made many 2004 top-ten lists:[38]

- 1st – Mark Kermode, BBC Radio Five Live

- 2nd – J. Hoberman, Village Voice

- 3rd – Overall, Village Voice

- 4th – Dennis Lim, Village Voice

- 5th – Jack Mathews, New York Daily News

- 8th – J. R. Jones, Chicago Reader

- n/a – David Sterritt, The Christian Science Monitor

- n/a – Ron Stringer, LA Weekly

The film received nine votes (with six from critics and three from directors) in the 2012 Sight & Sound polls.[10]

Accolades

[edit]| Award | Category | Recipients | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bodil Awards | Best Danish Film | Lars von Trier | Won |

| Best Actress | Nicole Kidman | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Stellan Skarsgård | Nominated | |

| Robert Award | Best Costume Design | Manon Rasmussen | Won |

| Best Screenplay | Lars von Trier | Won | |

| Best Editor | Molly Marlene Stensgård | Nominated | |

| Best Film | Lars von Trier | Nominated | |

| Best Cinematography | Anthony Dod Mantle | Nominated | |

| Best Production Design | Peter Grant | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Stellan Skarsgård | Nominated | |

| Best Director | Lars von Trier | Nominated | |

| Cannes Film Festival | Palme d'Or | Nominated | |

| European Film Awards | Best Cinematographer | Anthony Dod Mantle | Won |

| Best Film | Lars von Trier | Nominated | |

| Best Director | Nominated | ||

| Best Screenwriter | Nominated | ||

| Goya Awards | Best European Film | Nominated | |

| Russian Guild of Film Critics | Russian Guild of Film Critics Golden Aries Award for Best Foreign Actress | Nicole Kidman | Won |

| Best Foreign Film | Lars von Trier | Won | |

| Italian National Syndicate of Film Journalists | Best Director | Nominated | |

| Guldbagge Award | Best Foreign Film | Nominated | |

| Golden Eagle Award[39] | Best Foreign Language Film | Nominated | |

| Golden Trailer Awards | Best Independent | Nominated | |

| David di Donatello | Best European Film | Won | |

| Copenhagen International Film Festival | Honorary Award | Won | |

| Cinema Brazil Grand Prize | Best Foreign Film | Won | |

| Cinema Writers Circle Awards, Spain | Best Foreign Film | Won | |

| Guild of German Art House Cinemas | Best Foreign Film | Won | |

| Sofia International Film Festival | Best Film | Won |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Dogville". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 13 February 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Film #20033: Dogville". Lumiere. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ "Dogville (2003)". BBFC. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ "Dogville (2003)". Swedish Film Database. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ "Dogville". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ a b c "Dogville (2004)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- ^ "Lars Von Trier's Deconstructive, Avant Garde Cinema". The Playlist. 28 July 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "Synopsis, Movie Info, Moods, Themes and Related". AllMovie. 21 May 2003. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Dogville". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ a b "Dogville (2003)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 20 August 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ "The 21st-century movie Denis Villeneuve calls "genius"". faroutmagazine.co.uk. 1 December 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ von Trier in the DVD audio commentary track, Ch. 6

- ^ a b "Dogville Script - transcript from the screenplay and/Or Lars von Trier & Nicole Kidman movie".

- ^ Dogville: The Pilot. (from Dogville DVD, disc 2). 2003.

- ^ Kapla, Marit (11 June 2002). "Our Town". Filmmaker. Archived from the original on 24 September 2004.

- ^ Scott, A. O. (21 March 2004). "'Dogville' – It Fakes a Village". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (9 April 2004). "Reviews: Dogville". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 2 August 2010. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ "Dogville Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ^ a b "Dogville (2003)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ LaSalle, Mick (9 April 2004). "Dogville as poetic as it is powerful". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

mischievous, singular, and profound.

- ^ Hoberman, J. (16 March 2004). "The Grace of Wrath". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ^ Travers, Peter (23 March 2004). "Dogville". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ^ Foundas, Scott (25 March 2004). "Once Upon a Time in Amerika". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ Morrison, Alan. "Dogville Review". Empire. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (26 March 2004). "Seduced by ideas?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (4 April 2004). "Empty Set, Plot to Match". Time. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (9 April 2004). "Dogville Movie Review & Film Summary (2004)". Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ Axmaker, Sean (15 April 2004). "Von Trier's stylistic 'Dogville' is muzzled by its contempt for humanity". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ Taylor, Charles (23 March 2004). "Dogville". Salon. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ Brooks, Xan (23 December 2009). "Best films of the noughties No 8: Dogville". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077.

- ^ Best of a decade: film

- ^ "50 Best Movies of the Decade (2000–2009)". Paste Magazine. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ "The 21st Century's 100 greatest films". BBC. 23 August 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter; Clarke, Cath; Pulver, Andrew; Shoard, Catherine (13 September 2019). "The 100 best films of the 21st century". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "Quentin Tarantino's Top 20 Favorite Films". xfinity.com. Archived from the original on 10 January 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ^ Quentin Tarantino's Favourite Movies from 1992 to 2009... 4 April 2011. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b "Dogville". Box Office Mojo.

- ^ "2004 Film Critic Top Ten Lists". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 27 May 2008. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ Золотой Орел 2003 [Golden Eagle 2003] (in Russian). Ruskino.ru. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

Sources

[edit]- Tiefenbach, Georg (2010). Drama und Regie: Lars von Triers Breaking the Waves, Dancer in the Dark, Dogville. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann. ISBN 978-3-8260-4096-2.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Dogville at IMDb

- Dogville at AllMovie

- Dogville at Box Office Mojo

- Dogville at Rotten Tomatoes

- Dogville at Metacritic

- Dogville Archived 14 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine at AboutFilm.com: analysis by Carlo Cavagna

- On the Nature of Dogs, the Right of Grace, Forgiveness and Hospitality: Derrida, Kant, and Lars Von Trier's Dogville by Adam Atkinson

- Newsweek review[dead link]

- BBC Collective review Archived 6 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Dogville, or, the Dirty Birth of Law theoretical essay Archived 14 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- 2003 films

- 2000s avant-garde and experimental films

- 2000s British films

- 2000s English-language films

- 2000s French films

- 2000s gangster films

- 2000s German films

- 2000s Italian films

- 2000s Swedish films

- 2003 crime drama films

- 2003 independent films

- Arte France Cinéma films

- British avant-garde and experimental films

- British gangster films

- British independent films

- British thriller films

- Canal+ films

- Danish avant-garde and experimental films

- Danish independent films

- Danish thriller films

- Dutch avant-garde and experimental films

- Dutch independent films

- Dutch thriller films

- English-language crime drama films

- English-language Danish films

- English-language Dutch films

- English-language Finnish films

- English-language French films

- English-language German films

- English-language independent films

- English-language Italian films

- English-language Norwegian films

- English-language Swedish films

- Fictional populated places

- Films about adultery in the United States

- Films about rape in the United States

- Films directed by Lars von Trier

- Films set in Colorado

- Films set in the 1930s

- Finnish avant-garde and experimental films

- Finnish independent films

- Finnish thriller films

- Foreign films set in the United States

- France 3 Cinéma films

- French avant-garde and experimental films

- French gangster films

- French independent films

- French thriller films

- German avant-garde and experimental films

- German gangster films

- German independent films

- German thriller films

- Italian avant-garde and experimental films

- Italian independent films

- Italian thriller films

- Les Films du Losange films

- Lionsgate films

- Norwegian independent films

- Norwegian thriller films

- Rape and revenge films

- Swedish avant-garde and experimental films

- Swedish independent films

- Swedish thriller films

- Zentropa films