Battletoads (1991 video game)

| Battletoads | |

|---|---|

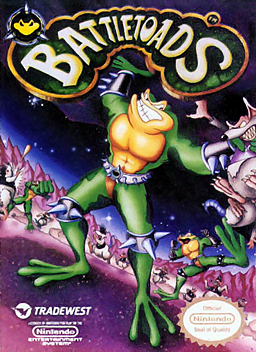

American NES cover art by Tim Stamper | |

| Developer(s) | Rare Arc System Works (MD/GG) Mindscape (AMI/CD32) |

| Publisher(s) | |

| Designer(s) | Tim and Chris Stamper Gregg Mayles |

| Programmer(s) | Mark Betteridge |

| Artist(s) | Kev Bayliss |

| Composer(s) | David Wise Hikoshi Hashimoto (MD/GG) Mark Knight (AMI/CD32) |

| Series | Battletoads |

| Platform(s) | NES/Famicom, Mega Drive/Genesis, Game Boy, Game Gear, Amiga, CD32 |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Beat 'em up, platform |

| Mode(s) | Single player, multiplayer |

Battletoads is a platform beat 'em up developed by Rare and published by Tradewest. It is the first installment of the Battletoads series and was originally released in June 1991 for the Nintendo Entertainment System. It was subsequently ported to the Mega Drive and Game Gear in 1993, to the Amiga and Amiga CD32 in 1994 (despite the former having been developed in 1992), and released with some changes for the Game Boy in 1993 in the form of Battletoads in Ragnarok's World. In the game, three space humanoid warrior toads form a group known as the Battletoads. Two of the Battletoads, Rash and Zitz, embark on a mission to defeat the evil Dark Queen on her planet and rescue their kidnapped friends: Pimple, the third member of the Battletoads, and Princess Angelica.

The game was developed in response to the interest in the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles franchise. It received mostly positive reviews upon release, with critics praising the graphics and variations of gameplay; however, many critics were divided over the game's difficulty. It won seven awards from the 1991 Nintendo Power Awards, and has since been renowned as one of the most difficult video games ever created.[2] It was later included in Rare's 2015 Xbox One retrospective compilation, Rare Replay.

Gameplay

[edit]

The game is a platform scrolling beat 'em up, with varying elements of racing, climbing and vehicle-based obstacle courses. Players start with three lives each time the game is started, which get replenished every time the player continues after getting defeated. The game contains no saving system or password features.[3] The player has a maximum of six hit points that can be replenished by eating flies.[4] While the levels of Battletoads vary greatly in gameplay style, the game is generally presented as a "beat'em up", in which players progress by defeating enemies while avoiding the hazards in the environment.[5]

Most of the attacks in the game have a "Smash Hit" variant, which triggers after a series of hits,[6] or as the final hit to the enemy, and delivers a powerful blow to the enemy, often enlarging the body part delivering the blow.

The Toads's regular hit is a regular punch,[7] with its Smash Hit variant, "Kiss-My-Fist". Also, while running, which is done by tapping left or right on the D-pad twice in a row, the toads can deliver a head-butt.[8] The head-butt's Smash Hit has the toads delivering a headbutt with giant ram horns, named the "Battletoad Butt". In addition, by standing close to them, most enemies can be picked up and thrown overhead.[7]

Due to the variety of gameplay styles between stages, many of the attacks are only usable in certain levels.[7] For example, while hanging on the Turbo Cable in the second level, the toads gain access to a kick, with its Smash Hit variant called "Swingin' Size Thirteens", a giant punch similar to Kiss-My-Fist, named the "Turbo Thwack", and "BT Bashing Ball" in which the character shape-shifts into a wrecking ball when hanging next to a wall.[9] In 2D levels, the toads can perform an uppercut, and its Smash Hit variation, called "Jawbuster".[7] Also, in certain levels, a move is available in which the toads clasp both hands to bash an enemy into the ground, named "Nuclear Knuckles".[7] After an enemy is buried by Nuclear Knuckles, the toads can use "the Punt" which involves repeatedly kicking their head,[7] ending with its Smash Hit version, named the "Big Bad Boot".[10][7]

Certain objects can also be used as weapons,[11] such as legs from defeated Walkers,[12] beaks from ravens,[9] pipes on the walls of Intruder Excluder,[13] and flagpoles from the Dark Queen's tower.[14]

Side-scrolling stages are generally presented as having an isometric perspective, while platforming stages that feature vertical progression are presented in 2D, which allows the player characters to crouch by pressing down. Several levels in the game feature sections in the form of an obstacle course, where the players must dodge a series of obstacles with speed increasing as the level progresses.[15] Other types of level include two "tower climb" levels, a descent to a chasm while hanging from a rope, a level with underwater sections, a maze chase riding a unicycle-style vehicle, a platforming "snake maze", and a race level in which the players have to fall as quickly as possible through countless platforms to reach the bottom of a tower before an enemy does. Hidden in four of the levels are "mega warp" points, which, when reached, allow the players to automatically advance by two levels.[15][16]

Plot and levels

[edit]Professor T. Bird and the three Battletoads, Rash, Zitz, and Pimple, are escorting Princess Angelica to her home planet using their spacecraft, the Vulture, for her to meet her father, the Terran Emperor.[17] When Pimple and Angelica decide to take a leisurely trip on Pimple's flying car,[18][17] they are ambushed and captured by the Dark Queen's ship,[19][20] the Gargantua.[21] The Dark Queen and her minions have been hiding in the dark spaces between the stars following their loss to the Galactic Corporation in the battle of Canis Major.[17] Pimple then sends out a distress signal to the Vulture, alerting Professor T. Bird, Rash, and Zitz. Learning that the Gargantua is hidden beneath the surface of a nearby planet called Ragnarok's World, Professor T. Bird flies Rash and Zitz there in the Vulture to rescue them.[17] Between levels, the toads receive briefing comments from Professor T. Bird, along with teasing from the Dark Queen.

The professor drops the toads to the first level, Ragnarok Canyon, the surface of the planet guarded by axe-wielding Psyko-Pigs and Dragons that the player can fly on after taking them out;[22][23] its boss is the Tall Walker, which throws boulders the heroes must throw back at it while avoiding its lasers.[24] Then in the second level, named Wookie Hole, the toads descend through a downward-scrolling impact crater, where they face the threat of ravens that can cut off the toads' Turbo Cable,[25] plants named Saturn Toadtraps that eat toads,[23][26] Retro Blasters that pop out of the wall and shoot electrical bolts,[27] and Electro Zappers that form a line of 2,000 volts of energy.[27]

Ride levels include the third stage, the Turbo Tunnel, where the players dodges stone walls while riding on a Speed Bike and having to use ramps to get across long gaps;[28][29] the fifth level, Surf City, where the player bounces on water surfaces on a "Space Board" while dodging logs, whirlpools, mines, and spiked balls;[30] the seventh stage, Volkmire's Inferno, where the 'toads fly on the Toad Plane in a fire environment going through Force Fields and dodging fireballs and rockets;[31] and level eleven, the Clinger-Winger, where the toads ride on the stage's titular unicycles while being chased by a hypnotic energy orb, named the Buzzball.[32][33] All of them include a section of beat 'em up gameplay,[29] with Surf City being the location of a boss fight with Big Blag, the chief of the Dark Queen's rat army that can squash the Battletoads with his weighty blubber slam,[34] and Buzzball also serving as Clinger-Winger's boss.[35]

The fourth stage, the Ice Cavern, is a platforming level where the player has to use snowballs and ice blocks to destroy barriers while dodging those cold elements, as well as spikes and hedgehogs, and facing snowball-throwing snowmen.[36] Level six, Karnath's Lair, is a set of rooms that each consist of only one exit and multiple snakes moving in varied, twisting rectangular patterns that serve as platforms that the toads must traverse while also dodging spikes.[29][37] Intruder Excluder, the vertical-scrolling eighth stage, is a platform-oriented level involving several jumps on platforms, springs and through electric barriers between moving gaps in the platforms, avoiding obstacles such as rolling Big Balls, Snotballs, suction valves named Suckas and poisonous gas guns named Gassers. Its only beat 'em up consist of encounters with Sentry-Drones,[38][39][40][29] The player must get from the bottom to the top of the level, where a boss fight with the Queen's genetically modified biogen Robo-Manus takes place.[41][38] Level nine, Terra Tubes, is a mixture of a platforming and underwater stage, and the only instance of the toads swimming in the game; it involves the player going through the piping into the Gargantua, with sections including encounters with Mechno-Droids[12] and Steel-Beck duck creatures that guard the tubes,[42] chases from the Krazy Kog,[12] and rivers infested with spikes, sharks, electric eels named Elctra-Eels, and instant-attacking Hammerfish.[42][43]

The tenth level, the Rat Race, is one of two levels in Battletoads located in the Gargantua,[44] the other being the eleventh level, Clinger-Winger.[33] Rat Race is a downward vertical-scrolling stage with the same hazards and enemies as Intruder Excluder.[45] In the stage, the Dark Queen sends fast rodent Giblet to activate three bombs in the ship for it to explode, and the player must destroy the bombs them before the rat makes it to them.[23][45] After the bombs are successfully switched off, a showdown with the Queen's least quick-witted commander, General Slaughter who only attacks with his head, ensues.[46]

The Battletoads escape the ship and, in another upward-vertical-scrolling stage named the Revolution, go to the top of the Dark Queen's Tower; the level involves the camera being fixed to the toads' position while the rest of the scenery rotates along with the circular tower as the toads go around it with a three-dimensional effect.[47] In the level, a variety of platforms must be used as support in order to progress, including some that sink the longer the playable character is on them, those that disappear and re-appear, those that move around the tower, and springs; foes include oafs named Hornheads,[27] Shadow Clouds that either harm the player with poisonous gas or blow wind to change the player's speed,[32] Spiked Balls that rotate around the tower,[40] and Swellcheeks where player are required to hang from the flag poles to avoid being blown away by their wind power.[14][27]

Once the toads reach the top of the tower, they will battle the Dark Queen. Once defeated, the Queen claims it will not be the last they would see from her. She then turns into a whirlwind and flies into space,[48] "retreating into the shadowy margins of the galaxy to recoup her losses".[49] With Pimple and Princess Angelica rescued, the four are brought back into the Vulture and fly away from the planet.[50]

Development

[edit]It was a typical example of Rare's looking at what was popular and then putting our spin on it.

Gregg Mayles in a retrospective interview[5]

The game was developed by Rare and published by Tradewest. Rare founders Tim and Chris Stamper created the series in response to the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles craze of the early 1990s.[51] To create a contrast to the popular media franchise and other beat 'em ups of the time, Rare added extra mechanics in the game to help separate it from these genres, such as racing stages and climbing courses.[3] Rare decided early to take the game's art style and tone in a cartoony direction, both to distance Battletoads further from other beat 'em up franchises and to comply with Nintendo's restrictions on violence in games.[52]: 55

According to Rare artist Kevin Bayliss, the characters of Battletoads were conceived in order to "produce merchandise" on a mass scale, in a similar vein to Tim Burton's Batman.[5] Bayliss claims that he did most of the work on sketching the game's characters while Tim Stamper was largely responsible for translating the sketches and artwork into sprites.[52]: 55 Rare attempted to create variation through shifts in gameplay between levels, and intentionally made Battletoads "crazy hard" in order to increase its longevity. Bayliss frequently heard the team's programmer Mark Betteridge scream in anger after failing to complete levels he had assembled himself.[52]: 56 Despite their own difficulties, the team's consensus was that Battletoads was possible to complete with practice and skill.[52]: 57

The game underwent changes through early stages of development, and at one point was originally titled Amphibianz. Bayliss originally designed Battletoads as a Disney-themed video game, however as the game gradually became more violent, Bayliss took extra liberties to tone it down and restrict all usage of weapons in the game, whilst creating a sense of uniqueness for the characters.[5] According to Bayliss, the box art was designed by him but airbrushed and produced by Tim Stamper. Bayliss' initial design for the box art was rejected as the team felt that it failed to attract customers' attention, but the team was satisfied with their second and final revision.[52]: 56–57

Release and promotion

[edit]Battletoads was presented at the 1991 winter Consumer Electronics Show; an article about the event from Electronic Gaming Monthly claimed it to be "highly innovative."[53]

A few months after the initial North American release in June 1991 for the NES, Battletoads got a Japanese-localized release for the Famicom, getting distributed in Japan by NCS, as opposed to Tradewest.[54] This release featured several gameplay tweaks, which resulted in a marginally easier experience.[15]

Initial reception

[edit]| Publication | Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amiga | NES | Sega Genesis | SGG | |

| AllGame | N/A | 4.5/5[55] | 3.5/5[56] | N/A |

| Aktueller Software Markt | N/A | N/A | N/A | 4/12[57] |

| Amiga Format | CD32: 10%[58] | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Amiga Power | 9%[59] | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Computer and Video Games | N/A | 91%[16] | 86/100[61] | 60/100[60] |

| Dragon | N/A | 5/5[62] | N/A | N/A |

| Electronic Gaming Monthly | N/A | 9/10[63] | 7.5/10[b] | 7.25/10[a] |

| Famitsu | N/A | 30/40[66] | 26/40[68] | 24/40[67] |

| GameFan | N/A | N/A | 94.25%[c] | N/A |

| GamesMaster | N/A | N/A | 78%[71] | N/A |

| GameZone | N/A | 93/100[7] | 90/100[73] | 68%[72] |

| Joypad | N/A | N/A | N/A | 80%[70] |

| Mean Machines Sega | N/A | 93%[74] | 79/100[76] | 89/100[75] |

| Official Nintendo Magazine | N/A | 85%[29] | N/A | N/A |

| Player One | N/A | 93%[77] | N/A | N/A |

| VideoGames & Computer Entertainment | N/A | 9/10[78] | N/A | N/A |

Battletoads started at number 26 on Nintendo Power's July 1991 Top 30 list of NES games for Players' Picks only with 464 points,[81] rising to number 13 the following issue with 858 points.[82] In September 1991, it premiered on the actual Top 30 list at number 11 with 3,219 points, landing in the top ten of both respective lists for Players' Pick (number seven) and Pros' Picks (number six).[83] In the October 1991 issue, the game skyrocketed to the number-three spot on the overall list with 6,008 points,[84] remaining in that position in the November issue with 6,397 points.[85] By January 1992, the issue Nintendo Power turned the Top 30 list into a Top 20 list (as they added Top 20 rankings for games of other consoles), Battletoads budged to number two with 6,140 points that month,[86] staying in that ranking for three more consecutive issues but remaining out of the top spot due to having significantly less points than the long-lasting Super Mario Bros. 3 (1990).[87][88][89] Afterwards, the game remained in the top ten for 17 more consecutive months,[d] and eleven times in the top five.[e] The game still charted when the Top 20 NES list ended in November 1994, and most of the game's final eleven months on the chart were in the bottom half,[f] with only one of those months in February 1994 being in a top ten spot.[117]

Battletoads was greeted with mostly enthusiastic reviews upon release, with critics calling it one of the best all-time video games,[63] one of the best games of 1991,[118] one of the best all-time NES games,[74][62][16] and the greatest NES game of 1991.[63] The "innovative and fun"[119] presentation was frequently praised, particularly when it came to the cutscenes,[16][74] the cartoon style of the characters and attacks,[119][74][16][78][62][118] the music and sound,[16][62][29] multi-layer scrolling,[16][119][78][29] variety of colors,[74][118] humor,[7] and the first level gimmick of the Big Walker boss being from the perspective of the boss.[78][119][16] Only minor complaints were made, such as towards the sprites being too small,[74] the attacks looking too non-aggressive,[120] some backgrounds being a "bit bland on occasions,"[29] and flickering.[78]

Gameplay-wise, Battletoads was praised for its diverse gameplay styles,[74][29] addictiveness,[74][16][7] and motivating challenge level.[74][29] Rob Bright of Nintendo Magazine System explained that "progress isn't slow, but then it isn't a breeze,"[29] and Julian Rignall of Mean Machines wrote that it's "brilliantly designed to allow you to get just a little bit further each time you play, and give experts the potential to hone their skills and rack up enormous amount of bonus points."[74] Chris Bieniek appreciated the simplicity of the controls of its multiple speciality moves, particularly how attacks triggered by the B button change between levels.[78] The platforming bits, however, were criticized for having poor collision detection that result in cheap deaths;[29][74] reviewers from Sega Force also noted this problem in the Mega Drive port and called the game a "run-of-the-mill" platformer with unresponsive controls, "random" difficulty between levels, very little surprises, and "menial" objectives.[121]

Battletoads was nominated for the 1991 Nintendo Power Awards in nine categories, winning the first place in the categories: Graphics and Sound (NES), Theme and Fun (NES), Best Play Control (NES) and Best Multi-Player or Simultaneous (NES), it was also given the title of the Overall Best Game for NES of 1991.[122]

Later years

[edit]AllGame acclaimed Battletoads as a mixture of a "great sense of humor (especially in the two-player mode) with a surprisingly good storyline and near-perfect gameplay," also praising its "smooth and responsive" controls "fluid" character animation, and the stages being "huge, gorgeously rendered and full of surprises."[55] In a negative retrospective review, Spike ranked the game's ending as the sixth biggest letdown in video game history.[123]

In 1997, Nintendo Power ranked the NES version as the 89th best game on any Nintendo platform.[124] In 2010, UGO included it on their "Top 25 games that need sequels"[125] also featuring the Arctic Cavern level on the list of "coolest ice levels".[126] Topless Robot ranked Battletoads as the number one "least terrible Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles rip-off" in 2008,[127] also naming it as one of ten best beat-'em-ups of all time in 2010[128] and as one of ten video games that should have gotten toys in 2011.[129] In 2012, it was also listed among ten "classic videos games that deserve an HD remake" by Yahoo! News.[130] GamesRadar ranked it the 18th best NES game ever made, stating that "it was a fun game but its most notable element was its difficulty".[131] Jeremy Dunham of IGN listed Battletoads as the 40th best NES game of all time.[132]

Difficulty

[edit]Battletoads has been noted by critics for its extreme difficulty.[127][133][134] The game has even been included on numerous occasions among the hardest games ever made, including the number one spot according to GameTrailers.[135][136][137][138] A reviewer of Destructoid stated that despite the game's "brutal and unbalanced" difficulty, it was often remembered as one of the most "beloved titles" of the eight-bit generation.[139] A consumer guide named The Winner's Guide to Nintendo (1991), published upon the game's release, admitted the Turbo Tunnel level to be "one of the toughest challenges of any NES game."[140] In 2012, Yahoo! Games stated that the game was still widely recognised as one of the most difficult games ever made, particularly noting the chance of players accidentally killing their partner in two-player mode.[141] Nerdist remarks that Battletoads's sudden difficulty spike was intended to combat the video game rental industry; if the game was more difficult, then it would take longer to complete, and consumers would be more likely to purchase a retail cartridge instead of renting one.[142]

Hardcore Gaming 101 writer Eric Provenza analyzed Battletoads to be unlike other video games known for their difficulty, such as Ninja Gaiden (1989) and Adventure Island, in that it does not get harder gradually; there are different mechanics, enemies, and obstacles for each section, with no opportunities for players to familiarize themselves with them due to limited continues and lives and the absence of a password system or save feature. The game starts as "a quirky beat-em-up before rapidly shifting into high-speed obstacle courses and manic action platforming with very little cohesion."[143] Game Players explained that while most of the game's challenges involved patterns that could be memorized by playing the game several times, it had long section lengths and very few continues; he also noted the two-player involving both players having to start over a stage if only one player loses all of his lives.[118]

Legacy

[edit]The game's initial success led to Rare developing various sequels which would later become part of the Battletoads franchise. A spin-off game for the Game Boy, also titled Battletoads, was first released in November 1991.[144] Despite having the same box art and title as the NES release, Battletoads for the Game Boy is a separate game in the series, featuring different levels and mechanics from the original.[145]

Two direct sequels, Battletoads in Battlemaniacs and Battletoads & Double Dragon, were both released for various consoles in 1993,[146] with the latter being placed number 76 on IGN's "Top 100 NES Games of All Time" list.[147] Battletoads Arcade was released in 1994 to mediocre sales.[148]

A pilot episode for a Battletoads TV series was also produced by Canadian DIC Entertainment, in an attempt to capitalise on the popularity of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. The pilot originally aired in syndication in the United States on the weekend of Thanksgiving 1992, but it was never picked up as a full series.[149]

In July 2020, Megalopolis Toys announced a partnership with Rare to release a line of six-inch action figures based on the games.[150]

Ports

[edit]

Due to the extreme difficulty of the original NES Battletoads, almost all subsequent ports of the game went to varying measures to tone it down, in an attempt to make the game more accessible to casual players. This caused some of the more demanding levels to be modified, and some of them even removed altogether in certain versions of the game.[15]

In 1992 the game was ported to the Amiga home computers by Mindscape, though the Amiga version went on unreleased until 1994. A Mega Drive version developed by Arc System Works and a Game Gear version were released by Sega (in Europe and Japan) and Tradewest (in North America) during 1993.[151] The Mega Drive version features toned-down difficulty, as well as providing higher definition and more colourful graphics than the NES version.[15][152] The Game Gear port features downscaled graphics, also removing three levels and the two-player mode.[145] While the Genesis port was appreciated by critics for keeping the gameplay and humorous animations of the NES title, its presentation was criticized as not improved enough from its 8-bit predecessor,[153][65] with GamePro suggesting it lacked "soaring stereo orchestration," digitized voices, or even "one croak" to significantly differentiate it.[154]

Also in 1993, a Game Boy version of the game was released, titled Battletoads in Ragnarok's World. Like the Game Gear version, it is missing several levels and featured single-player support only.[155] Tim Chaney, European CEO of Virgin Interactive, purchased the Master System rights for Battletoads from Tradewest after the game found popularity in the United States and had planned to release a version for that console in 1993, but it never materialised.[156][157]

In 1994 Mindscape brought the game to the Amiga CD32 and released it together with the previously unreleased Amiga version. It had also planned ports for PC DOS and the Atari ST back for the originally intended 1992 release of the computer versions, but these two were never released.[158][145] A port for the Atari Lynx was also announced and planned to be published by Telegames, but it was never released.[159][160]

During E3 2015 it was announced that the NES version of Battletoads would be coming to the Xbox One as part of Rare Replay, a retrospective collection of 30 emulated classic games from Rare.[161] Rare Replay was released on August 4, 2015,[162] featuring a fix to a bug in the original game that made the eleventh level unplayable for player 2.[163]

Notes

[edit]- ^ In Electronic Gaming Monthly's review of the Game Gear version, two critics gave it an 8/10, one a 7/10, and another a 6/10.[64]

- ^ In Electronic Gaming Monthly's review of the Genesis version, two critics gave it an 8/10 and two others a 7/10.[65]

- ^ In GameFan's review of the Mega Drive/Genesis port, four critics each gave the game different scores: 92%, 96%, 94%, and 95%.[69]

- ^ [90][91][92][93][94][95] including another stay at number two in July 1992[96]

- ^ [97][98][99][100][101][102][103][104][105][106]

- ^ [107][108][109][110][111][112][113][114][115][116]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Taylor, Matt (21 June 1991). "Nintendo continues to lead parade of 8-bit products headed for market". The Daily Progress. p. 36.

Tradewest showed a final version of the "Battletoads," a green Turtle spin-off team hopping to stores in a week or two.

- ^ "Battletoads Won Seven Times in the 1991 Nintendo Power Nester Awards". Retrovolve. 2 August 2020. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ a b Buchanan, Levi (13 January 2009). "Battletoads Retrospective". IGN. Archived from the original on 29 September 2019. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- ^ NES instruction manual 1991, p. 18.

- ^ a b c d Rare Replay — The Making of Battletoads (YouTube video). Rare. 6 August 2015. Archived from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ^ Nintendo Power guide 1991, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Battletoads". GameZone. No. 11. September 1992. pp. 28–31.

- ^ NES instruction manual 1991, p. 3.

- ^ a b Nintendo Power guide 1991, p. 12.

- ^ NES instruction manual 1991, p. 17.

- ^ NES instruction manual 1991, p. 6.

- ^ a b c NES instruction manual 1991, p. 12.

- ^ Nintendo Power guide 1991, p. 28.

- ^ a b Nintendo Power guide 1991, p. 38–39.

- ^ a b c d e Harnett, Craig (17 August 2015). "The Toads are Back in Town: Celebrating Battletoads". Nintendojo. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i O'Connor, Frank (April 1992). "Battletoads review — CVG". CVG (25): 26. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d NES instruction manual 1991, p. 2.

- ^ Rare (June 1991). Battletoads. Tradewest.

Narration text: One day Pimple and Princess Angelica were out cruisin'

- ^ Rare (June 1991). Battletoads. Tradewest.

Narration text: When suddenly

- ^ Rare (June 1991). Battletoads. Tradewest.

Narration text: Pimple and the princess were captured by the Dark Queen and taken to a nearby planet.

- ^ Rare (June 1991). Battletoads. Tradewest.

Professor T. Bird: Hey 'Toads! The Dark Queen's kidnapped Pimple and Angelica and she's holding them in the Gargantua.

- ^ Nintendo Power guide 1991, p. 10.

- ^ a b c NES instruction manual 1991, p. 8.

- ^ Nintendo Power guide 1991, p. 11.

- ^ NES instruction manual 1991, p. 9.

- ^ Nintendo Power guide 1991, p. 12–13.

- ^ a b c d NES instruction manual 1991, p. 14.

- ^ Nintendo Power guide 1991, p. 14–15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Swan, Gus; Bright, Rob (October 1992). "Battletoads". Nintendo Magazine System. No. 1. pp. 84–87.

- ^ Nintendo Power guide 1991, p. 20–21.

- ^ Nintendo Power guide 1991, p. 26–27.

- ^ a b NES instruction manual 1991, p. 16.

- ^ a b Nintendo Power guide 1991, p. 36.

- ^ Nintendo Power guide 1991, p. 21.

- ^ Nintendo Power guide 1991, p. 37.

- ^ Nintendo Power guide 1991, p. 18–19.

- ^ Nintendo Power guide 1991, p. 22–23.

- ^ a b NES instruction manual 1991, p. 10.

- ^ Nintendo Power guide 1991, p. 28–29.

- ^ a b NES instruction manual 1991, p. 13.

- ^ Nintendo Power guide 1991, p. 29.

- ^ a b NES instruction manual 1991, p. 11.

- ^ Nintendo Power guide 1991, p. 30–31.

- ^ Nintendo Power guide 1991, p. 34.

- ^ a b Nintendo Power guide 1991, p. 34–35.

- ^ Nintendo Power guide 1991, p. 35.

- ^ Nintendo Power guide 1991, p. 38.

- ^ Rare (June 1991). Battletoads. Tradewest.

Dark Queen: No! This can't be true! My entire defense system, beaten by a couple of mucus-lobbing slime-jackets! Better disappear, real quick, before something really nasty happens! Adios, fountain freaks!

- ^ Rare (June 1991). Battletoads. Tradewest.

Narration text: And so, the Dark Queen is defeated once again – retreating into the shadowy margins of the galaxy to recoup her losses... until the next time...

- ^ Rare (June 1991). Battletoads. Tradewest.

Professor T. Bird: Okay, let's break out the sodas and fast and junk-food – it's party time!

- ^ Baker, Christopher Michael. "Battletoads synopsis". AllGame. All Media Network. Archived from the original on 14 November 2014. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Milne, Rorin (2021). "The Making of: Battletoads". In Jones, Darran (ed.). 100 Nintendo Games to Play Before You Die – Nintendo Consoles Edition (3rd ed.). Future plc.

- ^ "1991 Winter Consumer Electronics Show". Electronic Gaming Monthly. Vol. 4, no. 3. March 1991. p. 76.

- ^ "Battletoads". SuperFamicom.org. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021.

- ^ a b Foster, Joe. "Battletoads — Review". Allgame. Archived from the original on 11 December 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ Sackenheim, Shawn. "Battletoads — Review". AllGame. Archived from the original on 14 November 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ "Battletoads". Aktueller Software Markt (in German). August 1994. p. 115.

- ^ Bradley, Stephen (November 1994). "CD32 Games". Amiga Format. No. 65. p. 75, score on 74.

- ^ Pelley, Rich (October 1994). "Battletoads". Amiga Power (42). Future plc: 51. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Skews, Rik (March 1994). "Battletoads". Computer and Video Games. No. 150. p. 85.

- ^ Whitta, Gary (May 1993). "Battletoads". Computer and Video Games. No. 138. p. 47.

- ^ a b c d Lesser, Hartley; Lesser, Patricia; Lesser, Kirk (November 1992). "Battletoads" (PDF). The Role of Computers. Dragon. No. 187. p. 60. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ a b c Harris, Steve; Semrad, Ed; Alessi, Martin; Sushi-X (June 1991). "Battletoads". Electronic Gaming Monthly. Vol. 4, no. 6. p. 16.

- ^ Semrad, Ed; Carpenter, Dayton; Manueel, Al; Sushi-X (December 1993). "Battletoads". Electronic Gaming Monthly. Vol. 6, no. 12. p. 54.

- ^ a b Harris, Steve; Semrad, Ed; Alessi, Martin; Sushi-X (April 1993). "Battletoads". Electronic Gaming Monthly. Vol. 6, no. 4. p. 28.

- ^ "バトルトード [ファミコン] / ファミ通.com". www.famitsu.com. Archived from the original on 24 July 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ^ "Battletoads Summary (Game Gear)". Famitsu. Archived from the original on 8 January 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ "バトルトード". Famitsu. No. 226. April 1993. p. 38.

- ^ Skid; Brody; Slick, Tom; The Enquirer (February 1993). "Battletoads". GameFan. Vol. 1, no. 4. pp. 8, 16–18.

- ^ "Battletoads". Joypad (in French). No. 29. March 1994. p. 130.

- ^ "Battletoads". GamesMaster. No. 5. May 1993. pp. 68–69.

- ^ "Battletoads". Sega Zone. No. 18. April 1994. p. 59.

- ^ "Battletoads". Sega Zone. No. 6. April 1993. pp. 20–22.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Rignall, Julian (April 1992). "Battletoads review" (PDF). Mean Machines. No. 19. p. 56. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 May 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ^ "Battletoads". Mean Machines Sega. No. 19. May 1994. pp. 78–79.

- ^ "Battletoads". Mean Machines Sega. No. 8. May 1993. pp. 71–72.

- ^ Wolfen. "Battletoads". Player One (in French). No. 24. pp. 66–69. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Bieniek, Chris (May 1991). "Battletoads". VideoGames & Computer Entertainment. No. 28. pp. 42–43.

- ^ West, Neil (May 1993). "Battletoads". Mega. No. 8. pp. 54–55.

- ^ "Battletoads". Sega Power. No. 43. June 1993. pp. 38–40.

- ^ "Players' Picks". Nintendo Power. Vol. 26. July 1991. p. 90.

- ^ "Players' Picks". Nintendo Power. Vol. 27. August 1991. p. 90.

- ^ "Top 30". Nintendo Power. Vol. 28. September 1991. pp. 88–90.

- ^ "Top 30". Nintendo Power. Vol. 29. October 1991. p. 90.

- ^ "Top 30". Nintendo Power. Vol. 30. November 1991. p. 90.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 32. January 1992. p. 104.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 33. February 1992. p. 106.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 34. March 1992. p. 106.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 35. April 1992. p. 104.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 45. February 1993. p. 101.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 47. April 1993. p. 101.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 48. May 1993. p. 101.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 49. June 1993. p. 101.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 50. July 1993. p. 101.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 52. September 1993. p. 89.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 38. July 1992. p. 106.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 36. May 1992. p. 106.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 37. June 1992. p. 106.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 39. August 1992. p. 106.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 40. September 1992. p. 104.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 41. October 1992. p. 106.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 42. November 1992. p. 94.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 43. November 1992. p. 102.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 44. January 1993. p. 101.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 46. March 1993. p. 101.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 51. August 1993. p. 97.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 53. October 1993. p. 97.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 54. November 1993. p. 101.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 56. January 1994. p. 101.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 58. March 1994. p. 101.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 60. May 1994. p. 101.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 61. June 1994. p. 101.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 62. July 1994. p. 101.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 63. August 1994. p. 101.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 64. September 1994. p. 101.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 66. November 1994. p. 101.

- ^ "Top 20". Nintendo Power. Vol. 57. February 1994. p. 101.

- ^ a b c d Lundrigon, Jeff (August 1991). "Battletoads". Game Players. Vol. 3, no. 8. p. 71.

- ^ a b c d Boogie Man (May 1991). "Battletoads". GamePro. No. 22. pp. 26–27.

- ^ "Auch Kröten töten". Power Play (in German) (6/93): 116. June 1993. Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ "Battletoads". Sega Force. No. 17. May 1993. pp. 96–98.

- ^ "Nintendo Power Awards". Nintendo Power. No. 34. May 1992.

- ^ "The 10 Biggest Letdowns in Video Game Endings". Spike. 24 May 2010. Archived from the original on 20 November 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ^ "Best Nintendo games list". Nintendo Power. No. 100. September 1997.

- ^ Jensen, Thor (27 November 2010). "25 games that need sequels". UGO. Archived from the original on 8 March 2013. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- ^ BK. Thor Jensen (28 December 2010). "Arctic Caverns — The 20 Coolest Ice Levels". UGO.com. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ^ a b "The 9 Least Terrible Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles Rip-Offs". Topless Robot. 24 October 2008. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ^ "The 10 Best Beat-'Em-Ups of All Time". Topless Robot. 30 June 2010. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ^ Clarke, Jason (3 December 2011). "Ten Video Games that Should Have Gotten Toys". Topless Robot. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- ^ Stark, Chelsea (7 August 2012). "Classic Videos Games That Deserve an HD Remake — Yahoo! News". News.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ^ "Best NES Games of all time". GamesRadar. 16 April 2012. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ^ Dunham, Jeremy. "Battletoads 40 - Top 100 NES games". IGN. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- ^ Buchanan, Levi (13 January 2009). "Battletoads Retrospective". IGN. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ O'Brien, Jack (9 July 2013). "7 Dick Moves Everyone Pulled in Classic Video Games". Cracked.com. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ "Top Ten Most Difficult Games". GameTrailers. 12 August 2008. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- ^ News & Features Team (21 March 2007). "Top 10 Tuesday: Toughest Games to Beat". IGN. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- ^ "Top 10 hardest games ever". Virgin Media. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- ^ Steven Larson (6 January 2011). "Top 10 Most Difficult Games Ever". Youtube.com. Archived from the original on 12 June 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ^ "The Forgotten: Battletoads on the go and in the arcades". Destructoid. 25 September 2009. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ^ Consumer Guide: The Winner's Guide to Nintendo. 1991. p. 29.

- ^ Smith, Mike (13 July 2012). "10 Insanely Tough Games". Yahoo! Games. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ Seibold, Witney (20 June 2017). "Why Was BATTLETOADS So Damn Hard?". Nerdist Industries. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ Provenza, Eric (5 March 2015). "Battletoads". Hardcore Gaming 101. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ "Battletoads Game Boy overview". IGN. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ^ a b c Workman, Robert (11 May 2012). "The Games of Summer: Battletoads". GameZone. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ^ "Battletoads in Battlemaniacs overview". IGN. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ^ Harris, Craig. "Battletoads & Double Dragon: The Ultimate Team". IGN. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ^ Baker, Christopher Michael. "Battletoads Review". AllGame. All Media Network. Archived from the original on 14 November 2014. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ Ciolek, Todd (17 November 2008). "The 5 Best (and 5 Worst) One-Shot TV Cartoons Ever Made". Topless Robot. Voice Media Group. Archived from the original on 28 September 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ^ "Megalopolis Announces Battletoads, Clay Fighter, and Earthworm Jim, and More Retro Action Figures". The Toyark - News. 23 July 2020. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ "Battletoads — Mega Drive overview". IGN. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ^ Sackenheim, Shawn. "Battletoads AllGame review". AllGame. Archived from the original on 14 November 2014. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- ^ "Battletoads". EW.com. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ Scary Larry (April 1993). "Battletoads". GamePro. No. 45. pp. 40–41.

- ^ "Battletoads in Ragnarok's World". Giant Bomb. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021.

- ^ IGN Staff (1 March 2001). "Gamecube developer profile: Rare". IGN. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- ^ "Toad in the Hole!". Sega Master Force. September 1993. p. 8. Archived from the original on 19 February 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ^ "Mindscape advertising of the IBM PC, Commodore Amiga and Atari ST versions". Archived from the original on 29 September 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ Hands on Harry (December 1992). "Hands On Portable - Lynx". GameFan. Vol. 1, no. 2. DieHard Gamers Club. p. 69.

- ^ chris_lynx1989 (12 February 2003). "Unreleased Telegames, Lynx game – the Guardians - questions". AtariAge. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ McWhertor, Michael (15 June 2015). "Rare Replay for Xbox One includes 30 Rare games for $30 (update)". Polygon. Vox Media. Archived from the original on 17 June 2015. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- ^ Tamburro, Paul (15 June 2015). "Rare Replay Announced for Xbox One, Including Banjo-Kazooie, Conker's Bad Fur Day and Battletoads". Crave. Archived from the original on 22 July 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ^ McWhertor, Michael (9 July 2015). "Rare will fix Battletoads' nasty two-player glitch for Rare Replay". Polygon. Vox Media. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

Bibliography

[edit]- Battletoads (NES) instruction manual. Tradewest. 1991. pp. 1–20.

- "Battletoads". Nintendo Power. Vol. 25. June 1991. pp. 8–43.

External links

[edit]- Battletoads can be played for free in the browser at the Internet Archive (Game Gear)

- Battletoads at MobyGames

- GameTime (31 January 2019), Battletoads: The Story Behind The Hardest Video Game Ever Made, archived from the original on 15 November 2021

- 1991 video games

- Amiga games

- Arc System Works games

- Battletoads games

- Cancelled Atari Lynx games

- Cancelled Atari ST games

- Cancelled DOS games

- Cancelled Master System games

- Amiga CD32 games

- Cooperative video games

- Game Boy games

- Masaya Games games

- Multiplayer and single-player video games

- Nintendo Entertainment System games

- Platformers

- Game Gear games

- Sega Genesis games

- Side-scrolling beat 'em ups

- Tiger Electronics handheld games

- Tradewest games

- Video games developed in the United Kingdom

- Video games scored by David Wise

- Video games scored by Mark Knight

- Video games set on fictional planets

- Xbox One games

- Sega video games

- Mindscape games