Last week I noted in my review of the Australian government's Mid-Year Economic and Financial…

Austerity cultist Kenneth Rogoff continues to bore us with his broken record

One would reasonably think that if someone had been exposed in the past for pumping out a discredited academic paper after being at the forefront of the destructive austerity push during the Global Financial Crisis, then some circumspection might be in order. Apparently not. In 2010, Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff published a paper in one of the leading mainstream academic journals – Growth in a Time of Debt – which became one of the most cited academic papers at the time. At the time, they even registered a WWW domain for themselves (now defunct) to promote the paper and tell us all how many journalists, media programs etc have been citing their work. While one can understand the self-promotion by Rogoff and Reinhart, it seems that none of these media outlets or journalists did much checking. It turned out that they had based their results on research that had grossly mishandled the data – deliberately or inadvertently – and that a correct use of the available data found that that nations who have public debt to GDP ratios that cross the alleged 90 per cent threshold experienced average real GDP growth of 2.2 per cent rather than -0.1 per cent as was published by Rogoff and Reinhart in their original paper. So all their boasting about finding robust “debt intolerance limits” arising from “sharply rising interest rates” – and then “painful fiscal adjustments” and “outright default” were not sustainable. Humility might have been the order of the day. But not for Rogoff. He regularly keeps popping up making predictions of doom based on faulty mainstream logic.

I analysed the spreadsheet scandal in detail in this blog post – Elementary misuse of spreadsheet data leaves millions unemployed (April 17, 2013).

His latest intervention (November 28, 2024) –

Europe’s Economy Is Stalling Out – was published by Project Syndicate, which regularly gives space to these nonsensical mainstream articles.

The simple proposition that Rogoff offers is:

As Germany and France head into another year of near-zero growth, it is clear that Keynesian stimulus alone cannot pull them out of their current malaise. To regain the dynamism and flexibility needed to weather US President-elect Donald Trump’s tariffs, Europe’s largest economies must pursue far-reaching structural reforms.

And those structural reforms have to tackle the:

… bloated and sclerotic welfare states to blame?

Apparently, those that hold to the most basic macroeconomic rule that spending equals output and income and drives employment growth are “detached from reality”.

Welcome to my unreal world.

Rogoff claims that the “France’s aggressive stimulus policies” are unsustainable and are not supporting growth.

But the information he presents is highly selective.

He tells the readers that the fiscal deficit has risen to “6% of GDP” but the latest data that is adjusted for seasonality and calendar events (public holidays etc) shows the fiscal deficit is 5.5 per cent in the June-quarter 2024, down from 5.7 per cent in the September-quarter 2023.

So, in fact, the government sector is reducing its net spending footprint in the economy – which is anti-stimulus.

But the story gets more complicated when we look at a longer data span.

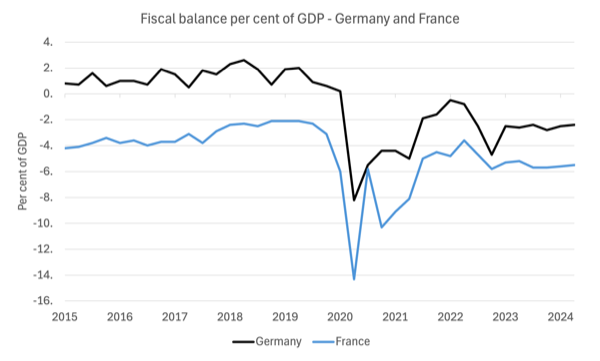

The following graph shows the fiscal positions for Germany and France since the March-quarter 2015 as a percent of GDP,

The last observation from Eurostat was for the June-quarter 2024.

The obvious point is that France generally runs larger fiscal deficits (as a per cent of GDP), meaning that the government sector is larger there relative to Germany.

The second point is that the pandemic and the fiscal support required to manage that disaster drove fiscal deficits up in both nations – more or less by the same percentage point variation.

Yet, France then reacted in a stronger contractionary shift only to have to move back towards stimulus against relatively quickly.

Finally since the pandemic fiscal deficits have remained higher in both nations than the pre-pandemic levels yet the fiscal adjustment towards lower deficits has actually been larger for France.

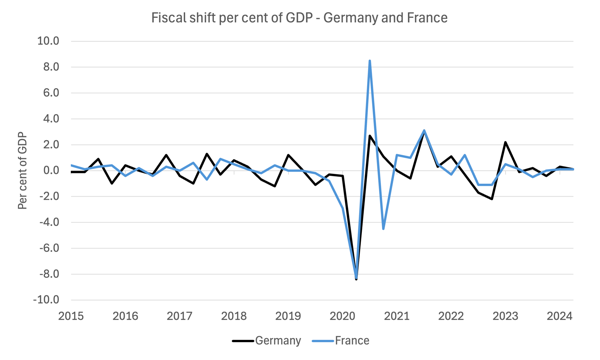

The next graph helps us see that last point.

It shows the fiscal shift each quarter in percent of GDP – so a positive number is a shift to lower deficit to GDP ratio, a contractionary move, while a negative number is a stimulus fiscal shift.

Note that these shifts cannot be understood as being the exclusive result of discretionary policy shifts.

That is because the fiscal balance contains both discretionary and non-discretionary (automatic stabiliser) components.

So an increasing deficit might be because the government has chosen to engage a stimulus strategy and/or because the non-government economy has lower economic activity (less spending) and the falling employment has reduced tax revenue and/or increased welfare spending.

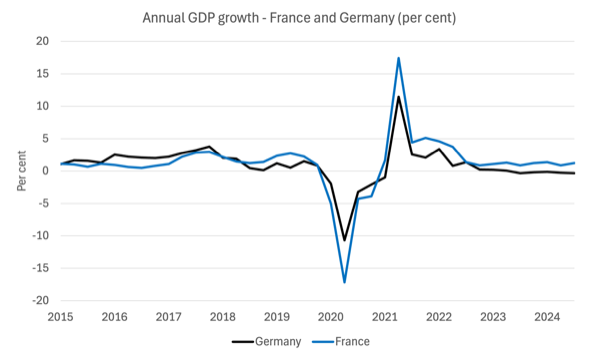

The next graph shows the respective annual GDP growth rates since the March-quarter 2015 (up until the September-quarter 2024).

It is clear that as the chaos from the early years of the pandemic resolved somewhat, France has consistently recorded a higher (albeit modest) annual growth than Germany, the latter has been mired in recession since the September-quarter 2023.

France has so far avoided a shift into recession.

Can we conclude that the higher fiscal deficits in France have helped it avoid recession while the lower deficits in Germany (about half the level of France’s fiscal deficit) have biased it towards recession?

Almost certainly that is the case, which refutes Rogoff’s principle conjecture that higher deficits do nothing to support economic growth.

Further, what would we expect to happen if France suddenly started reducing net fiscal spending (through expenditure cuts and/or tax hikes)?

Well, economic growth in France would quickly head towards recession – no doubt about that.

We also have to understand the ‘larger’ and ‘smaller’ deficit outcome more clearly.

A ‘larger’ fiscal deficit (as a percent of GDP) with a stable GDP growth rate is providing support to incomes and employment and its ‘size’ reflects the current spending of the non-government sector.

The government sector may have taken the discretionary decision to have a larger footprint – for example, by imposing higher tax rates on the non-government sector.

However, the larger deficit might just mean that non-government sector spending is weaker and tax revenue is falling etc.

Both situations, however allow us to conclude that from that given position, any discretionary attempt to reduce the deficit will reduce growth, incomes and employment.

I was talking to a podcast yesterday and they asked me what might happen if Elon Musk and his gang close down a lot of government departments.

While the Musk zealots might claim they are freeing the US of wasteful and unnecessary bureaucracy, the spending that runs those departments is necessary to sustain the current GDP growth and employment levels, given non-government spending choices.

So if they scrap those departments and do not increase spending elsewhere to offset the chosen spending cuts then the US will likely fall into recession.

While we might take the view that a specific area of government spending is wasteful according to our preferences and values, at the current time, that spending is supporting employment and income generation.

The point of the graphs is to show that while France did provide increased discretionary stimulus during the early years of the pandemic, it has recently been reducing its net public spending relative to GDP.

In part that is why the GDP growth rate has declined since the bounce-back quarters through 2022, even though it remains positive and not that around the post-Euro average rate.

Rogoff claims that “debt markets have recently woken up to the risks posed by France’s ballooning debt” (yields have risen) and that means that its long-term growth prospects are limited.

He then cited the Reinhart/Rogoff work from the GFC as if it remained an authority.

Further he conflates the European experience with that of Japan as if there is a valid comparison.

In this 2010 blog post – Watch out for spam! (January 25, 2010) – I noted that R&R are content to conflate nations that operate within totally different monetary systems (gold standards, convertible non-convertible, fixed and flexible exchange rates, foreign currency and domestic currency debt etc).

They seem oblivious to the fact that there can never be a solvency issue on domestic debt issued by a fiat-currency issuing government, such as Japan, irrespective of whether the debt is held by foreigners or domestic investors.

R&R pull out examples of sovereign defaults way back in history without any recognition that what happens in a modern monetary system with flexible exchange rates is not commensurate to previous monetary arrangements (gold standards, fixed exchange rates etc). For example, Argentina in 2001 is also not a good example because they surrendered their currency sovereignty courtesy of the US exchange rate peg (currency board).

Their scandalous 2010 American Economic Review paper also fell into the error of conflating monetary systems.

Japan’s low GDP growth rate has little to do with the public debt ratio and all to do with negative population growth and a particular non-government bias towards household saving.

The bond markets don’t drive up yields on Japanese government bonds.

Rather they queue up for every scrap of debt they can get and at various times have been willing to accept negative yields on 10-year debt issues.

Europe is a different case altogether because 20 of the 27 EU Member States surrendered their currency sovereignty and have to rely on bond market borrowing to run fiscal deficits.

And, the debt those Member States issue is subject to credit (default) risk, which means that the bond markets will demand higher yields in order to loan funds if they believe a Member State is moving towards higher default risk and the ECB doesn’t signal it will buy that Member States debt in secondary bond markets.

The problem is not fiscal policy positions per se but rather the fact that the Eurozone Member States have chosen to retain their fiscal policy responsibilities (under the so-called subsidiarity principle, which was just a part of the deliberate aim of the European Commission to straitjacket the Member States in the austerity bias favoured by the neoliberal designers of the system), while using a foreign currency (the euro), which they do not issue.

Rogoff is dead wrong when he lumps the currency-issuing states in with the Eurozone states, as if they face the same fiscal constraints.

They clearly don’t.

But his observations about fiscal space in the Eurozone being limited are correct, even though he doesn’t really understand the reasoning.

In relation to Germany, he thinks that the government “has ample room to revitalize its crumbling infrastructure and improve its underperforming education system”, although he doesn’t discuss the reason for the parlous situation – the Stability and Growth Pact fiscal rules which the German government has weaponised.

Inasmuch as the bund is sought after and Germany maintains its extreme austerity bias, then he is correct, the Government could expand net public spending without spurring immediate bond market fear about solvency.

But his solution to Germany’s austerity-damaged society is, in effect, to expand the microeconomic changes that Germany undertook in the early days of the common currency (the so-called Hartz reforms), which was part of a deliberate strategy to ‘game’ the nation’s trade partners within the common currency by increasing its trade competitiveness once it lost the ability to manipulate the Deutschmark exchange rate.

That strategy deregulated the labour market and created a secondary tier of low-paid, insecure workers and starved the domestic economy of spending.

The large export surpluses that eventuated created a big investment pool that had nowhere to go (earn a return) in the domestic economy and found returns in the debt buildup and real estate bubbles in other Eurozone nations, such as Spain, etc.

Soon after the whole unsustainable bubble burst (the GFC) and we know what happened then.

Rogoff acknowledges that the Hartz policies “made the German labor market significantly more flexible than France’s”, but fails to mention the unsustainable imbalances they created throughout the common currency, which manifest in the GFC crisis.

Some countries have not recovered from the crisis.

Rogoff’s claim is that countries like France and Germany have to adopt a scorched earth approach (deregulation, pension cuts, wage cuts, abandon job security, and the like) in order to grow faster because more spending will not help.

Yet towards the end of his article he says:

The economic outlook would have been much bleaker if not for Europe’s enduring appeal as a tourist destination, particularly among American travelers, whose strong dollars are propping up the industry. Even so, the outlook for 2025 remains lackluster. Although European economies could still recover, Keynesian stimulus will not be enough to sustain robust growth.

Think about the contradiction in that closing statement.

GDP growth in Europe, particularly France, has been propped up by tourist spending.

In other words, increased spending does stimulate growth.

And when the commercial sector is taking orders for new goods and service provision they don’t first of all ask whether the buyer is an American tourist spending Euros on some tourist attraction or whether it is the French government ordering supplies for its public sector institutions.

A Euro spent is a Euro of extra output if there is idle capacity.

And there is plenty of that across Europe at present.

Conclusion

I guess the edict from Max Plank that ‘paradigms change one funeral at a time’ means that Rogoff will continue to be given an audience for as long as he is around.

And that reduces the quality of our public discourse.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

A quick question for Bill / others in the know from an MMT newbie, albeit perhaps off the topic of “spending does stimulate growth” which seems such a ‘duh’ point.

It seems to me there is a quantitative difference between government money buying “supplies for its public sector institutions” and tourists “spending Euros on some tourist attraction”.

Government money would require the entering of digits into bank accounts which would overall increase the amount of money in circulation, correct? To those who say “inflation is more euro bills chasing the same amount of products”, increasing the amount of money in circulation might stimulate growth but also stimulate inflation. Hence don’t do it.

Tourists spending Euros on the other hand are exchanging their currency for already existing euros: the existing money pool is unchanged meaning less inflationary impact and a valuable source of foreign exchange.

i.e. some forms of spending are more desirable than others. That seems to be the mainstream argument. Not anti-spending per se, just spending they see as desirable (which is never government—they spend it on the ‘wrong things’).

Do I have that right or wrong?

Many thanks,

Darren

Dear Darren (at 2024/12/04 at 1:10 pm)

Thanks for your comment and question.

First, all spending stimulates nominal income growth.

Second, you then are really asking what the proportion of that nominal growth is real – that is, non-inflationary.

Third, to answer that question, we need to know about the state of capacity utilisation.

In the case of an economy that is fully employed, then any additional nominal spending will likely lead to inflationary pressures because it would result in a bidding contest for the existing resources.

However, if there were idle resources and productive capacity that can be brought back into use then there is no reason for those pressures to emerge, depending on what the nominal spending growth was seeking to purchase.

So, a government would be stupid if it tried to buy products or services from a sector that was already operating at full capacity.

But if it stimulated sectors that had spare capacity then increased nominal income would be equivalent to increased real income and higher employment (probably).

That puts your statement “inflation is more euro bills chasing the same amount of products” into context. If there is truly the same amount of products and that is finite then of course, increased spending will only stimulate nominal income and the price level will rise.

I hope that helps.

best wishes

bill

The question in every MMT sleuths mind is: What happened to Mosler’s pal Vince Reinhardt? Did his wife Carmen kill him? Or has she got him locked in a basement? Or is it just that Carmen wears the pants in their household? All good humanitarians are holding out for the latter.

Many thanks for your reply Bill, it is much appreciated.

I take from your reply that the idea of the “same amount of products” is a contestable notion dependent on firstly the amount of resources sitting idle. Therefore, given unemployment rates worldwide, it is unlikely to be the case that any government spending would would be for the “same amount of products”, as the spending would stimulate growth and the use of those idle resources (except for in certain sectors that might be “operating at full capacity”).

Government spending would therefore be non-inflationary until there were no idle resources left.

Thanks again, I now know how to address that line of argument at the Christmas table “discussion” 🙂

Darren

Mainstream economists use the Quantity Theory of Money as a way of explaining how demand-pull inflation can be caused by “more money chasing a limited quantity of goods and services”. The Quantity Theory of Money equation of MV = PQ is not only used deceptively, it is plain wrong!

Mainstream economists will ask you to imagine what will happen to P (the average price level of new goods and services) if M (the money supply) increases with a constant V (velocity of circulation, which varies negligibly over a year). First, they will say something like “Assume M rises and Q (the quantity of new goods produced) remains constant”. They won’t tell you why you should assume a constant Q. However, for Q to not rise, one must assume no spare productive capacity – that is, full employment. Anyone who keeps just half on eye on things is aware that full employment is, at best, the exception, not the norm. In fact, most countries haven’t enjoyed full employment for around fifty years. Of course, if there is spare productive capacity, which means Q can rise as M increases, it is possible for P to remain constant as M varies (no demand-pull inflation). Deception!

But the real error is the assumption that an increase in M will necessarily do something to the right-hand side of the equation. PQ is GDP – the monetary value of new domestically-produced goods and services. PQ will only rise if nominal spending on new domestically-produced goods and services increases. Total nominal spending on new domestically-produced goods and services = total financial injections spent on new domestically-produced goods and services (Ā) x the expenditure multiplier.

Each new financial injection (primary spending) becomes income to the factors of production used to produce the goods demanded by the primary spending. Some of this income will leak from the real economy in the forms of taxes (permanently destroyed, never to be seen again); spending on imported goods and services (a leakage to the ROW); and savings (unspent after-tax income). What doesn’t leak from the real economy is after-tax income respent on new domestically-produced goods and services (which mobiles additional factors of production). This additional spending is some of the same money initially injected into the real economy (primary spending) that is passing through more hands (the expenditure multiplier process). This additional spending (induced spending) becomes a further round of income of which some leaks out of the real economy in the form of taxes, import spending, and savings. However, the magnitude of each new round of induced spending → income → leakages → spending gets smaller until it reduces to zero, at which point the expenditure multiplier process ceases. By now, all initial financial injections will have leaked from the real economy, which is why, ultimately, financial injections = financial leakages.

What is true is: Ā x expenditure multiplier = PQ.

But MV is not the same as [Ā x expenditure multiplier].

In other words, MV ≠ [Ā x expenditure multiplier]. Thus, if M rises because someone has borrowed newly-created credit money to purchase shares, a Picasso painting, or Bitcoin – a financial injection NOT spent on new domestically-produced goods and services (therefore, not increasing Ā) – this might push up share prices and the value of a fixed number of Picasso paintings and Bitcoin, but it won’t increase Q, let alone P.

The Quantity Theory of Money – just more mainstream economic myth, lies, and deception.

Looks like our dear Chancellor has been taking advice from Rogoff.