History

From a six-student night school in rented rooms in downtown Hartford to the magnificent Gothic halls of the Elizabeth Street campus, the evolution of the UConn School of Law is an example of why “change is good.” Since its founding in 1921 as the private Hartford College of Law, the Law School has changed—many times and with the times. It has occupied eight locations in 85 years. Each change of location reflects the institution’s ever-widening horizons.

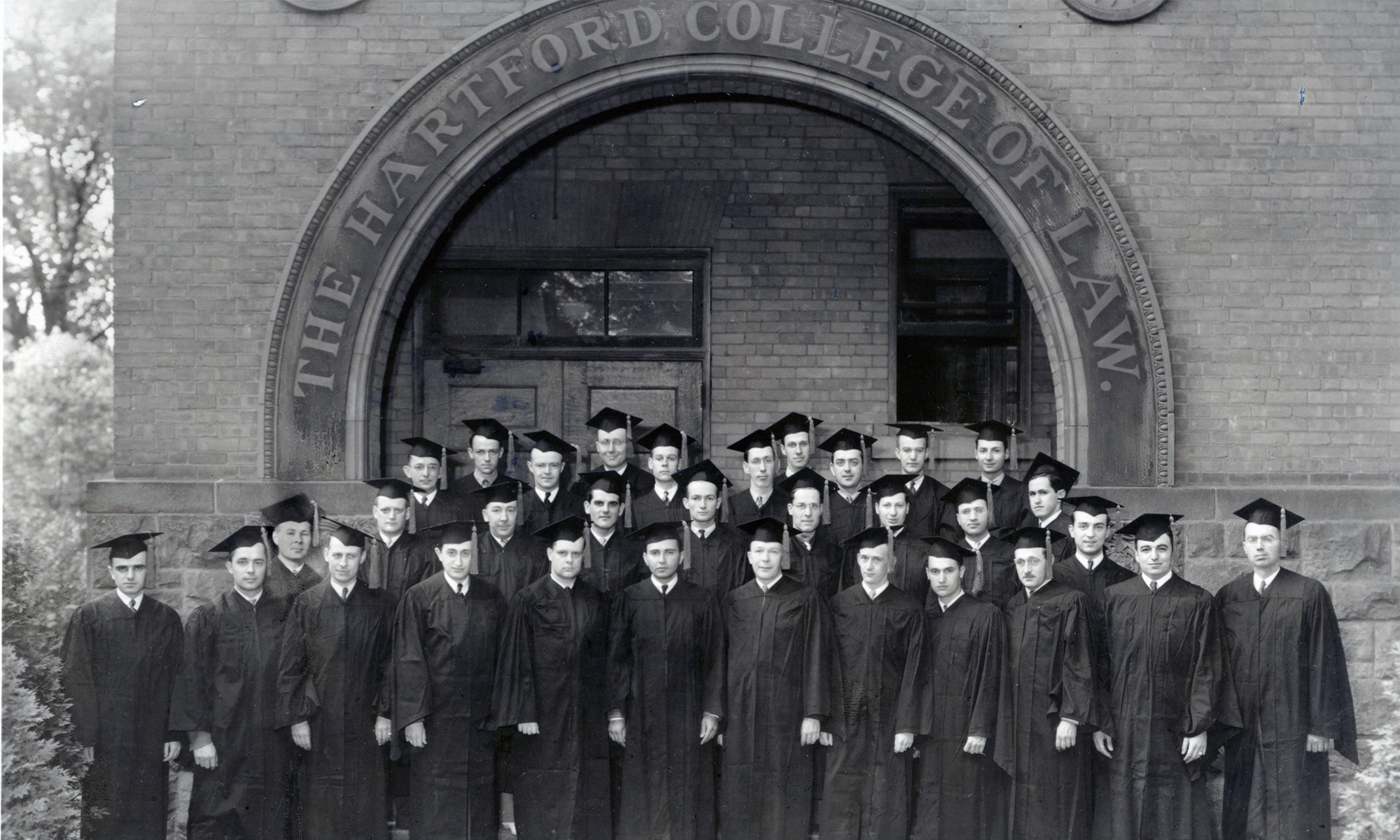

1921-1930 The Early Years: Practicality was Paramount

The founders of the Hartford College of Law, George William Lillard and Caroline Eiermann Lillard, established a practical school with practical goals. The college was intended to provide a legal education for employees of Hartford-based insurance companies and other “industrial and mercantile organizations of Hartford.” Classes were held at hours and at a location convenient for working people—at night in downtown Hartford. The College’s classes also provided supplementary preparation for law students studying for the bar examination. The first graduating class included Miss J. Agnes Burns, the first graduate of the College to be admitted to the Connecticut Bar and the first female attorney to appear before the Connecticut Supreme Court.

The College changed quarters three times in three years, beginning in rented rooms in the top floors of the Hartford Wire Works at 94 Allyn Street in 1921: “One room over a bird store” quipped Roger Wolcott Davis, president of the board of trustees and a former teacher, in a 1948 Founder’s Day speech. In 1922 the school offices decamped to more rented rooms in the top floors of the Hartford Life Insurance Company Building at the corner of Asylum and Ann Streets, while classes were held at the Hartford-Connecticut Trust Company at the corner of Main and Pearl Streets. In 1926 the College moved to the Graybar building at 51 Chapel Street where it occupied the top floor of a two-story building. “We were always near the top,” said Davis.

1930 – 1940 Accreditation: 44 Niles Street

The kindergarten building of West Middle School at 44 Niles Street housed the College of Law for ten years, from 1930 to 1940. This sturdy stone building’s solidity stands as an apt metaphor for the College’s determination to provide a solid legal education and, in doing so, earn ABA accreditation.

By 1930 the country was in the midst of the Great Depression and the College was on shaky financial ground. Minutes of trustee meetings from the period express concern about students’ overdue tuition payments and the cost of operating the College. “Mr. Lillard talked with a lumber man about the storm windows and they would cost approximately $6 or $7 for each window and that would run into another $100,” the June 17, 1936 board minutes state. A poignant paragraph from minutes of the same meeting describes the plight of “three boys who are behind in their tuition” and concludes with an agreement that they work off their debts by seeding the College’s lawn. Tuition at that time was $100 per year.

Despite the uncertainty of the times, the College of Law flourished. The student body grew to 100 part-time night students taught by three full-time instructors. The Niles Street quarters included a spacious classroom that doubled as an assembly room, three smaller class-rooms, an instructors’ room, library and storage space.

The College began to comply with the standards of the American Bar Association by requiring two years of college before students could enter. On June 17, 1932, Farwell Knapp, an instructor for eighteen years and later president of the board of trustees, was appointed part-time dean and in September 1933, Thomas A. Larremore, Professor of Law at Washburn College in Kansas, was appointed the first full-time dean. That same month the College was approved by the American Bar Association and accredited by the Examining Committee of the Connecticut Bar Association.

Between 1934 and 1939, there were other significant changes: the Charter was amended to organize the College of Law as a nonprofit educational corporation; William F. Starr was appointed a full-time instructor; and the day division program was added to include full-time students.

1940 – 1964 War and Peace: 39 Woodland Street

The Law School’s relationship with Hartford Seminary (then called Hartford Theological Seminary) began in 1940 with the purchase of Jacobus Hall at 39 Woodland Street. This gracious structure had been the home of Professor M. W. Jacobus, a former dean of the seminary. The purchase price of the house and the three-acre lot was $25,000 and an additional $20,000 was allocated for alterations and furnishings to transform the residence into a school. A detailed list of “Expenditures Contemplated” to accomplish the transformation included “remove existing linen closet shelving and refinish as instructor’s office—$110.” (One can only hope that the linen closet had a window.) Jacobus Hall was a luxurious space for the students, providing not only classrooms but also a lounge, living quarters on the third floor and a library in the solarium.

When the United States entered World War II in 1941, enrollment in the College dropped precipitously as students enlisted in the armed services. The College was saved from closure by the University of Connecticut’s agreement to take over responsibility for it. On June 1, 1943, the College of Law’s board of trustees leased the school to the University for five years and on September 1, 1948 conveyed full title; the Hartford College of Law became the University of Connecticut School of Law. During the war, the decision was made to close temporarily the day school. The last class of three students graduated in February 1944. According to Harriet S. Olzendam, first editor in chief of the Starr Report, “The first class to attend the University of Connecticut School of Law was the first class to have 100% of its members pass the state bar examination.”

The evening division operated continuously throughout the war and the day division reopened in February 1946, when returning veterans nearly doubled the Law School’s enrollment. At the end of the war, Dr. Bert E. Hopkins was hired as dean; he made it his mission to expand the School’s facilities to accommodate post-war growth. A new wing was added to Jacobus Hall in 1953 providing a small library and a few classrooms. This addition provided a measure of relief for a time, but in only a few years the building was once again bursting at the seams. There were not enough classrooms or faculty offices and no space for a student lounge, as it had been taken over for instructional space. Books were stored wherever space could be found—in the basement boiler room, the butler’s pantry, and the attic.

1964 – 1984 A Brand New Campus: 1800 Asylum Avenue, West Hartford

In 1961, the University of Connecticut contracted with Frederic C. Teich, architect of Jorgensen Auditorium on the Storrs campus, to design a new home for the Law School at 1800 Asylum Avenue on property formerly owned by Phoenix Mutual Life Insurance Company. Completed in spring of 1964, the building was of “modern classic design,” with an exterior of red brick walls, stone panels and trim, and aluminum sashes.

The nation was in turmoil: 1964 was the year of the civil rights movement’s Freedom Summer, the Free Speech Movement at the University of California at Berkeley, and rioting in many of the nation’s major cities. President Lyndon B. Johnson told his national security advisor, McGeorge Bundy, that the Vietnam War was “…just the biggest damn mess I ever saw.”

On April 30, 1964, The West Hartford News produced a special section that hailed the opening of the Law School’s new campus as a “most significant event in the life of our state university.” One wonders whether an educational institution and its new building would be the subject of such celebration today. The News supplement included a two-page photo layout of five young

law students, Joseph Weigand ’65, Steven Buchman ’65, Joel Mandell ’66, John Jepson ’64, and David Brown ’64, dressed in suits and ties, “stepping over carpenter’s tools and around ladders,” inspecting the soon-to-be completed building. An article described the Law School’s new home as having “an airy bright atmosphere created by large windows and the pleasant pastel color scheme.” Also singled out for praise was the building’s indirect lighting, “which shows off beautifully the Formica-top tables and red armchairs.” The law library was touted as the centerpiece of the campus, with a collection of 50,000 books, a new 3M photocopier and two tape recorders.

Joel Mandell, one of the clean-cut young men in The West Hartford News photo, was not sorry to leave Woodland Street. “It was refreshing,” Mandell recalls, “to move from a relatively little house with little desks to a nice new place with a spacious library where we could sit and study.” In the early years at the Asylum Street campus, the Law School was closed off from the political and social upheaval in the world. Both Mandell and John Jepson, another of the students in the photo, remember that students, many of them married, were “there for getting a degree, not paying attention to world affairs.”

The new building attracted more students. There was a 40% increase in admissions in the academic year 1964-65, bringing enrollment to a combined day and evening total of 373 students. No doubt the increase was due partly to the desire to avoid or postpone the draft for a war which many students opposed, but their interest in the law reflected another aspect of society in the sixties: the desire to do meaningful work and to make a difference in the world. Designed to accommodate a full-time student population of 350, by the summer of 1977 the building could not accommodate adequately 460 students; there were no offices for part-time faculty, and older books were put in storage or shelved in the basement. In its 1975 report, the ABA noted that the School’s facilities did not meet ABA standards and threatened revocation of accreditation.

By the time Phillip Blumberg was appointed dean in 1974, the once-admired Asylum Avenue campus was no longer the pride of the Law School. Dean Blumberg was committed to making the institution one of the outstanding state law schools in the nation, and he saw the School’s facilities as a major obstacle to the realization of that goal. In his 1976-77 annual report, Blumberg enumerated the building’s many inadequacies, including lack of classroom and library space as well as room for audio-visual and computer equipment “required for a high quality legal education.” The dean also made the argument about the relationship of place to possibility, environment to achievement. “The building,” he wrote, “is lacking in aesthetic design…. It is an unimaginative building which makes it difficult for students to think largely of themselves and their aspirations.”

During this time, Hartford Seminary had moved out of its buildings on Elizabeth Street and wanted to sell the campus. Over a two-year period, a broad coalition of legislators, University of Connecticut administrators, Dean Blumberg, faculty, students and trustees of Hartford Seminary lobbied for the State to purchase the Hartford Seminary campus for the Law School. State Senator Audrey Beck of Mansfield was one of the move’s major proponents in the legislature. Beck, a former member of the faculty, declared that “whenever I visit the Law School, I am impressed by the students and depressed by the facility.” In June of 1978, Governor Ella Grasso signed legislation authorizing the expenditure of $6 million to purchase and renovate the 27½ acre Hartford Seminary campus.

1984 – Present Architecture and Aspiration: 55 Elizabeth Street

Built between 1922 and 1926, the six spectacular collegiate Gothic buildings of the Elizabeth Street campus and its European-style quadrangle were designed by the firm of Allen and Collens of Boston, architects of New York City’s Riverside Church. They were built of Connecticut Buckingham granite; stone from the same quarry was used in the construction of a 1955 addition on the right side of Avery Arch (now called Starr Hall) as well as in the new library, completed in 1996. The original buildings of Hartford Seminary were named MacKenzie, Hosmer, Knight, Avery and Hartranft Halls. With the exception of Hartranft Hall (now called Chase Hall), named after Chester D. Hartranft, the visionary president of the Seminary, and MacKenzie Hall, named after William Douglas MacKenzie, who oversaw the moving and building project, the other buildings were named for benefactors who financed their construction. Newton Case, for whom the library within Avery Hall was named, is said to have asked President Hartranft what the Seminary needed and when he learned it was a library, replied, “Go and buy one.” The cost of the rest of Avery Hall (now called Starr Hall) was shouldered by Samuel P. Avery, whose likeness can be found, fittingly enough, on a statuary piece in the main corridor bearing a representation of the building on his shoulder. Avery Hall, the architectural center of the campus, was completed in 1926. At that time, the main driveway from Elizabeth Street passed through the arch in the building’s 120-foot tower.

The transformation from a theological seminary to a secular institution for the study of the law took six years and $8.75 million. Most of the interior renovations involved adding elevators and ramps, and alterations to comply with fire and safety standards. MacKenzie Hall, originally a dormitory for women, became the new home of the state Attorney General’s Office. A non-denominational chapel, now Chase 110, was an ideal setting for trial practice work with its rows of seating and raised platform.