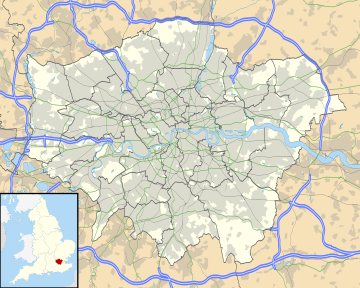

Mile End is an area in London, England and is located in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is in East London and part of the East End. It is 4.2 miles (6.8 km) east of Charing Cross.[1] Situated on the part of the London-to-Colchester road called Mile End Road, it was one of the earliest suburbs of London.

It was also known as Mile End Old Town; the name provides a geographical distinction from the unconnected former hamlet called Mile End New Town. In 2011, Mile End had a population of 28,544.[2]

History

editToponymy

editMile End is recorded in 1288 as La Mile ende.[3] It is formed from the Middle English 'mile' and 'ende' and means 'the hamlet a mile away'. The mile distance was in relation to Aldgate in the City of London, reached by the London-to-Colchester road.[3] In around 1691 Mile End became known as Mile End Old Town, because a new unconnected settlement to the west and adjacent to Spitalfields had become known as Mile End New Town.[3]

Beginnings

editWhilst there are many references to settlement in the area, excavations have suggested that this was a rural area with very few buildings before 1300.

The road from the Aldgate (on London's defensive wall) to Colchester is known as Mile End Road when it passes through the district. In the medieval period it was known as Aldgatestrete to reflect the starting point of the road, it later became known as the Great Essex Road to reflect its destination.

The River Lea, the historic western boundary of Essex, was once much wilder and formed a formidable obstacle. The road, which has existed since at least Roman times, once forded the river at Old Ford in northern Bow. It moved to its present-day alignment after the foundation of Bow Bridge in 1110. The new bridge was around 900 metres (0.56 miles) south-east of the ford, requiring a new alignment to be established.

The area running alongside Mile End Road was known as Mile End Green, a large open common which became known as a place of assembly for Londoners, as reflected in the name of Assembly Passage, a short road 470 meters (0.29 miles) west of the Stepney Green tube station.

Peasants' Revolt

editIn 1381 an uprising against the tax collectors of Brentwood quickly spread; firstly in the surrounding villages and then throughout the South-East of England. However it was the rebels of Essex led by a priest named Jack Straw, and the men of Kent led by Wat Tyler, who marched on London. On 12 June the Essex rebels (comprising 100,000 men) camped at Mile End. On the following day the men of Kent arrived at Blackheath. On 14 June, the teenaged King Richard II rode to Mile End where he met the rebels and signed their charter. The king subsequently had the leaders and many rebels executed.[4]

Expansion

editSpeculative developments existed by the end of the 16th century and continued throughout the 18th century. It developed as an area of working and lower-class housing, often occupied by immigrants and migrants new to the city.

In 1811 Bancroft Road Cemetery at Globe Fields was opened for its first burial by the separatist "Maiden Lane synagogue in Covent Garden". By 1884 it was in disrepair. The cemetery was full by 1895. The synagogue became bankrupt in 1907 and incorporated back into the larger Western Marble Arch Synagogue.[5]

In 1820 the New Globe pub opened next to the new "Globe Bridge", with its licence possibly transferring from a nearby pub called the Cherry Tree which closed at around this time.[6]

Mile End Hospital was originally an infirmary for the local workhouse, established in 1859.[7] In 1883 the facility was rebuilt as the "Mile End Old Town Infirmary". A training school for nurses was added in 1892.[7] During the First World War it served as a military hospital.[7] In 1930 it was renamed "Mile End Hospital" and then joined the National Health Service when it commenced in 1948.[7] It was renamed "the Royal London Hospital (Mile End)" in 1990 but reverted back to "Mile End Hospital" in 1994. Also in June 1990 the Bancroft Unit for the Care of the Elderly opened at Mile End Hospital having moved from Bethnal Green.[8] In 2012 it was taken under the management of Barts Health NHS Trust.[9]

In 1882 novelist and social commentator Sir Walter Besant proposed a Palace of Delight[10] with concert halls, reading rooms, picture galleries, an art school, various classes, social rooms and frequent fêtes and dances. This coincided with a project by the philanthropist businessman Edmund Hay Currie to use money from the winding up of the "Beaumont Trust",[11] (together with subscriptions) to build a "People's Palace" in the East End. Five acres of land were secured on the Mile End Road and the Queen's Hall was opened by Queen Victoria on 14 May 1887. The complex had a library, swimming pool, gymnasium and winter garden by 1892 which provided an eclectic mix of populist entertainment and education. A peak of 8,000 tickets were sold for classes in 1892. By 1900, a Bachelor of Science degree was introduced, awarded by the University of London.[12] The building was destroyed by fire in 1931 but the Draper's Company (major donors to the original scheme) invested to rebuild the technical college and create Queen Mary College in December 1934.[13] A new "People's Palace" was constructed in 1937 by the Metropolitan Borough of Stepney in St Helen's Terrace. This finally closed in 1954.[14]

In 1902 Mile End tube station was opened by the Whitechapel & Bow Railway (W&BR). Electrified services started in 1905. The first services were provided by the District Railway (now the District line). Then the Metropolitan line followed in 1936 (this part was renamed in 1988 as the Hammersmith & City line.) In 1946 (as part of the Central line eastern extension) the station was expanded and rebuilt by Stanley Heaps (Chief Architect of London Underground) and his assistant Thomas Bilbow. Services started on 4 December 1946. Following nationalisation of the W&BR, full ownership of the station passed to London Underground in 1950.[15]

In 1903 The Guardian Angels Church (designed by Frederick Arthur Walters) opened. It was paid for by Henry Fitzalan-Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk as a memorial to his youngest sister Lady Margaret Howard, who had performed charitable work in the East End.[16]

In 1933 a ring known as Mile End Arena (covered with a canopy, crumbling walls and rickety corrugated iron) was opened behind Mile End station. It was only used in summer and closed in 1953.[17]

Second World War

editAs well as suffering heavily in earlier blitzes, Mile End was hit by the first V-1 flying bomb to strike London. On 13 June 1944, that "doodlebug" impacted next to the railway bridge on Grove Road, an event now commemorated by a blue plaque. Eight civilians were killed, 30 injured, and 200 made homeless by the blast.[18]

After the Second World War, a part of Mile End remained mostly derelict for many years, until it was cleared to extend Mile End Park.[19]

Contemporary

editThe Stepney Green Conservation Area was designated in January 1973, covering the area previously known as Mile End Old Town. It is a large Conservation Area with an irregular shape that encloses buildings around Mile End Road, Assembly Passage, Louisa Street and Stepney Green itself. It is an area of exceptional architectural and historic interest, with a character and appearance worthy of protection and enhancement. It is situated just north of the medieval village of Stepney, which was clustered around St. Dunstan's Church.[20]

In 1990 Ragged School Museum opened in the premises of the former site of the Copperfield Road Ragged School.[21]

On 17 June 1995, the Mile End Stadium hosted a gig by Britpop band Blur where 27,000 fans saw them supported by the Boo Radleys, Sparks, John Shuttleworth, Dodgy and the Cardiacs.[22]

A groundbreaking project funded by the Millennium Commission called the Green Bridge opened in 2000 (a pedestrian and cyclist separation structure over the A11 (Mile End Road) connecting the two halves of Mile End Park to form a linear park). It included new retail frontages.[citation needed]

The St Clement's Hospital site was closed in 2005, with services transferred to a new Adult Mental Health Facility at Mile End Hospital in October 2005.[23]

The Palm Tree pub building was Grade II listed in 2015 by Historic England.[24]

The Night Tube service began at Mile End tube station (on the Central line) on 19 August 2016.[25] Since 2016, northern Mile End has fallen under the remit of the Bow Roman Road Neighbourhood Forum. This includes the shops under The Green Bridge on the northern side of Mile End Road (A11), the Mile End Climbing Wall, and Palm Tree.[26]

A 165 year old historically important pub which had been one of the few buildings locally to survive the blitz, "The Carlton" closed in May 2018. This was an important part of local community history. It was sold to Trustee Properties Ltd who obtained permission from Tower Hamlets Council in 2017 to develop five flats but not to demolish the ground floor of the pub. But they demolished the whole building without approval.[27]

Governance

editMile End formed a hamlet within the large ancient parish of Stepney, in the Tower division of the Ossulstone hundred of Middlesex. Although formally part of the historic (or ancient) county of Middlesex, military and most (or all) civil county functions were managed more locally, by the Tower Division (also known as the Tower Hamlets) under the leadership of the Lord-Lieutenant of the Tower Hamlets.

The role of the Tower Division ended when Mile End became part of the new County of London in 1889. The County of London was replaced by Greater London in 1965.

For more local government, Mile End was grouped into the Stepney poor law union in 1836, becoming a single civil parish for poor law purposes in 1857.

It formed part of the Metropolitan Police District from 1830.

Upon the creation of the Metropolitan Board of Works in 1855 the vestry of Mile End Old Town became an electing authority. The vestry hall was located on Bancroft Road.

The parish became part of the County of London in 1889 and in 1900 it became part of the Metropolitan Borough of Stepney.

In 1965 Stepney was incorporated into the London Borough of Tower Hamlets.

There was a Mile End Parliament constituency from 1885 to 1950, which was notable for being one of two constituencies in the UK to elect a Communist Party MP Phil Piratin to the House of Commons between 1945 and 1950. The area now is covered by the Bethnal Green and Bow and Poplar and Limehouse constituencies.

Geography

editMile End, which is in London's East End has an unusual landmark, the "Green Bridge" (known affectionately as the banana bridge, due to its yellow underside). This structure (designed by CZWG Architects and opened in 2000) carries Mile End Park over the busy Mile End Road. The top of the bridge includes garden and water features and some shops and restaurant space built in below.

Ackroyd Drive Greenlink, Tower Hamlets Cemetery Park and Mile End Park form a large green corridor.[28][29] The Greenlink is a linear site bisected by roads into five rectangular plots. From the south these are Cowslip Meadow, allotments, Blackberry Meadow, Peartree Meadow and Primrose Meadow.[30]

Sport and leisure

editMile End has a Non-League football club, Sporting Bengal United F.C., which plays at Mile End Stadium. The Mile End Skate Park provides a protected recreational space for skate sports. There are many green spaces in Mile End, including the Tower Hamlets Cemetery Park, one of the "Magnificent Seven" cemeteries.

Media

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2015) |

The neighbourhood was depicted unfavourably in the pop band Pulp's 1995 song "Mile End", which was featured on the Trainspotting soundtrack.[31] The song describes a group of squatters taking up residence in an abandoned 15th-floor apartment in a run-down apartment tower.

In 2009, the music video for "Confusion Girl" by electropop musician Frankmusik was filmed in Mile End Park and Clinton Road, Mile End.[32]

In 2011, the music video for "Heart Skips a Beat" by Olly Murs and Rizzle Kicks was filmed in Mile End's skate park.

Transport

editRail

editMile End tube station is on the London Underground Central, District and Hammersmith & City lines, all of which connect Mile End directly to the East End, City of London and Central London. The Central line also links the area directly to Stratford and Essex in the east and London's West End. The station is in London fare zone 2.[33][34]

Buses

editThere are bus stops on Mile End Road, Burdett Road and Grove Road.

London Bus routes 25, 205, 277, 309, 323, 339, 425, D6, D7 and night buses N25, N205 and N277 stop in the area.

Buses link Mile End directly to destinations across London, including Canary Wharf, the City of London, King's Cross, Paddington and Stratford.[35][36]

Road

editThe A11 (Mile End Road) passes east–west through Mile End, linking the locale to Aldgate in the west and Stratford in the east. At Stratford, the road meets the A12 where eastbound traffic can continue towards Ilford, the M11 (for Stansted Airport) and destinations in Essex.

The A1205 (Grove Road/Burdett Road) carries traffic northbound towards Victoria Park and Hackney. The road terminates to the south at the A13 near Limehouse and Canary Wharf.

Air pollution

editThe London Borough of Tower Hamlets monitors roadside air quality in Mile End. In 2017, average Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2) levels in the locale failed to meet the UK National Air Quality Objective of 40μg/m3 (micrograms per cubic metre).[37]

An automatic monitoring site in Mile End recorded a 2017 annual average of 48μg/m3. Alternative monitoring sites on Mile End Road also failed to meet air quality objectives. A site at the junction with Globe Road in nearby Stepney recorded 52μg/m3 as a 2017 average, whilst a site at the junction with Harford Street recorded 41μg/m3.[37]

Exposure to higher concentrations of NO2 has been linked to lung disease and respiratory problems.[38]

Cycling

editMile End is on London-wide, national and international cycle networks. Public cycling infrastructure in the locale is provided by both Transport for London (TfL) and the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. Routes include:

- National Cycle Route 1 (NCR 1) – a long-distance leisure cycle route between Dover, Kent and the Shetland Islands, Scotland and forms part of the National Cycle Network. The route passes through Mile End Park on traffic-free shared use paths. In North London, the route runs from Canary Wharf to Enfield Lock.[39]

- Cycle Superhighway 2 (CS2) – a commuter cycling route from Aldgate in the City to Stratford in the east. The route runs signposted, unbroken and traffic-free on cycle track for the majority of the route. The route follows the A11 (Mile End Road) through Mile End, and the track is coloured blue.[40] It was upgraded between Bow and Aldgate and was completed in April 2016, with separated cycle tracks replacing cycle lanes along the majority of the route.[41]

- Cycleway between Hackney and the Isle of Dogs – a proposed commuter cycle route made in 2019. According to current proposals, the southern portion of the route will run unbroken, signposted and traffic-free on cycle track between Mile End and Canary Wharf.[42]

- EuroVelo 2 ("The Capitals Route") – EuroVelo 2 is an international leisure cycle route between Moscow, Russia and Galway, Ireland. Through Mile End, it follows the route of NCR 1.[43][44]

- Regent's Canal towpath – a shared use path from Limehouse to Angel. The route is unbroken and traffic-free for its entire length, and can be accessed at Mile End through Mile End Park. The route links Mile End directly to Hackney and Dalston en route.[45][46]

Notable people

edit- Mabel Lucie Attwell (1879–1964), the British illustrator for children's books (married to painter and illustrator Harold Cecil Earnshaw), was born in Mile End.[47]

- Rokhsana Fiaz, the Labour Mayor of Newham since 2018, was born in Mile End hospital.[48][49]

- Craig Fairbrass, actor in EastEnders and London Heist.[50]

- Muzzy Izzet, professional footballer who was a part of the Turkey side that reach the semi-finals of the 2002 FIFA World Cup.[51]

- Charles Pope, (1883–1917) Recipient of the Victoria Cross in June of 1917 was born in Mile End.[52]

- Pop singer Samantha Fox was born here.

- Jason Tindall, the former professional footballer and current assistant manager at Newcastle United, is from Mile End.[53]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Distance between Mile End Underground Station, Tower Hamlets, Greater London, England, UK and Charing Cross, London, England, WC2N 5, UK (UK)". distancecalculator.globefeed.com.

- ^ "Mile End – Hidden London". hidden-london.com.

- ^ a b c Mills, D. (2000). Oxford Dictionary of London Place Names. Oxford.

- ^ R. B. Dobson, editor, (2002), The Peasants' Revolt of 1381 (History in Depth) ISBN 0-333-25505-4; a collection of source materials

- Alastair Dunn (2002), The Great Rising of 1381: The Peasant's Revolt and England's Failed Revolution, ISBN 0-7524-2323-1

- ^ "Edith's Streets: Great Eastern Railway to Ilford Globe Town". 20 July 2014.

- ^ "New Globe, 359 Mile End Road, Mile End E3". pubshistory.com. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Mile End Hospital". Lost hospitals of London. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ "Mile End Hospital - Our history". www.bartshealth.nhs.uk.

- ^ Meriel Clunas. "Mile End Hospital – Our history". Bartshealth.nhs.uk. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ In Walter Besant All Sorts and Conditions of Men (1882)

- ^ In 1841, John Barber Beaumont died and left property in Beaumont Square, Stepney to provide for the education and entertainment of people from the neighbourhood. The charity – and its property – was becoming moribund by the 1870s, and in 1878 it was wound up by the Charity Commissioners, providing its new chair, Sir Edmund Hay Currie, with £120,000 to invest in a similar project. He raised a further £50,000 and secured continued funding from the Draper's Company for ten years (The Whitechapel Society, below)

- ^ G. P. Moss and M. V. Saville From Palace to College – An illustrated account of Queen Mary College (University of London) (1985) pages 39–48 ISBN 0-902238-06-X

- ^ The People's Palace The Whitechapel Society accessed 5 July 2007 Archived 11 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Origins and History Queen Mary, University of London Alumni Booklet Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine accessed 5 July 2007

- ^ "Transport Act, 1947" (PDF). The London Gazette. 27 January 1950. p. 480. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 July 2013.

- ^ Mile End: The Guardian Angels, Taking Stock: Catholic Churches in England and Wales, accessed 11 February 2017

- ^ "History of Mile End tube station". 28 September 2018.

- ^ "The First Flying Bomb to Hit London". WW2 People's War. BBC Southern Counties Radio. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^ Roberts, Alison (12 January 1994). "Best and worst of art bites the dust". The Times. The Library of Mu. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^ "Stepney Green". Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ^ "Ragged School Museum". Time Out London. 10 July 2018.

- ^ "Blur live at Mile End Stadium, 1995". Veikko's Blur Page. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ "Hospitals". Derelict London.

- ^ Historic England. "The Palm Tree public house, Mile End (1427142)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ^ "Over 50,000 journeys completed on London's first Night Tube services". Transport for London. 20 August 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ "Boundary".

- ^ "Anger as 165-year-old East End pub that survived the Blitz is flattened by developer". 28 September 2018.

- ^ "Ackroyd Drive Greenlink". Local Nature Reserves. Natural England. 13 July 2013. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ^ "Map of Ackroyd Drive Greenlink". Local Nature Reserves. Natural England. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ^ Noticeboard on the site

- ^ Snapes, Laura (22 January 2018). "From Barking to Bow: the songs that champion London's less glamorous corners". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ "Frankmusik – Confusion Girl". capitalfm.com.

- ^ "London's Rail & Tube services" (PDF). Transport for London (TfL). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2019.

- ^ "Night Tube and London Overground map" (PDF). Transport for London (TfL). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2019.

- ^ "Buses from Mile End" (PDF). Transport for London (TfL). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2019.

- ^ "Buses from Mile End Stadium and Burdett Road" (PDF). Transport for London (TfL). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2019.

- ^ a b "London Borough of Tower Hamlets Air Quality Annual Status Report for 2017" (PDF). London Borough of Tower Hamlets. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2019.

- ^ "Nitrogen Dioxide" (PDF). World Health Organization (WHO). p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 April 2018.

- ^ "Route 1". Sustrans. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019.

- ^ "CS2 Stratford to Aldgate" (PDF). Transport for London (TfL). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 April 2019.

- ^ "Cycle Superhighway 2 upgrade". Transport for London. Archived from the original on 9 September 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ^ "Cycling and walking improvements between Hackney and the Isle of Dogs". Transport for London (TfL). Archived from the original on 15 May 2019.

- ^ "EuroVelo 2". EuroVelo.

- ^ "EuroVelo 2: United Kingdom". EuroVelo.

- ^ "Cycling". Canal & River Trust. Archived from the original on 7 April 2019.

- ^ "Regent's Canal". Canal & River Trust. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019.

- ^ Dalby, Richard (1991), The Golden Age of Children's Book Illustration, Gallery Books, pp. 132–3, ISBN 0-8317-3910-X

- ^ "Almost 4,000 people may have been denied vote by election ID pilots". The Guardian. 3 May 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ "About". Rokhsana Fiaz. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ Fairbass, Craig. "Biography". Craig Fairbass.

- ^ "Former Premier League star is on a Mission". 4 December 2014.

- ^ Time: < 5 mins (18 August 2021). "The Highest Honour #38 | Charles Pope | Reg Rattey | The Cove". Cove.army.gov.au. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Cherries: We're stronger than ever says Tindall". Bournemouth Echo. 16 October 2012.

Bibliography

edit- William J. Fishman, East End 1888: Life in a London Borough Among the Laboring Poor (1989)

- William J. Fishman, Streets of East London (1992) (with photographs by Nicholas Breach)

- William J. Fishman, East End Jewish Radicals 1875–1914 (2004)

- Nigel Glendinning, Joan Griffiths, Jim Hardiman, Christopher Lloyd and Victoria Poland Changing Places: a short history of the Mile End Old Town RA area (Mile End Old Town Residents’ Association, 2001)

- Derek Morris Mile End Old Town 1740–1780: A social history of an early modern London Suburb (East London History Society, 2007) ISBN 978-0-9506258-6-7

- Alan Palmer The East End (John Murray, London 1989)

- Watson, Isobel (1995). "From West Heath to Stepney Green: Building development in Mile End Old Town, 1660–1820". London Topographical Record. Vol. XXVII. London Topographical Society. pp. 231–256.