The Group of Eight (G8) was an intergovernmental political forum from 1997–2014.[1] It had formed from incorporating Russia into the G7, and returned to its previous name after Russia was expelled in 2014.[2]

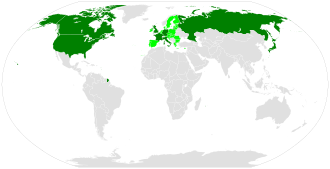

The forum originated with a 1975 summit hosted by France that brought together representatives of six governments: France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, thus leading to the name Group of Six or G6. The summit came to be known as the Group of Seven in 1976 with the addition of Canada. Russia was added to the political forum from 1997, which the following year became known as the G8. In March 2014 Russia was suspended indefinitely following the annexation of Crimea, whereupon the political forum name reverted to G7.[3][4][5] In January 2017, Russia announced its permanent withdrawal from the G8.[2] However, several representatives of G7 countries stated that they would be interested in Russia's return to the group.[6][7][8] The European Union (or predecessor institutions) was represented at the G8 since the 1980s as a "nonenumerated" participant, but originally could not host or chair summits.[9] The 40th summit was the first time the European Union was able to host and chair a summit. Collectively, in 2012 the G8 nations comprised 50.1 percent of 2012 global nominal GDP and 40.9 percent of global GDP (PPP). The G8 countries were not strictly the largest in the world nor the highest-income per capita, but they do represent the largest high-income countries.

"G7" can refer to the member states in aggregate or to the annual summit meeting of the G7 heads of government. G7 ministers also meet throughout the year, such as the G7 finance ministers (who meet four times a year), G7 foreign ministers, or G7 environment ministers.

Each calendar year, the responsibility of hosting the G8 was rotated through the member states in the following order: France, United States, United Kingdom, Russia (suspended), Germany, Japan, Italy, and Canada. The holder of the presidency sets the agenda, hosts the summit for that year, and determines which ministerial meetings will take place.

In 2005, the UK government initiated the practice of inviting five leading emerging markets – Brazil, China, India, Mexico, and South Africa – to participate in the G8 meetings that came to be known as G8+5. With the G20 major economies growing in stature since the 2008 Washington summit, world leaders from the group announced at their Pittsburgh summit in September 2009 that the group would replace the G8 as the main economic council of wealthy nations.[10][11] Nevertheless, the G7 retains its relevance as a "steering group for the West",[1] with special significance appointed to Japan.[12]

History

editFollowing 1994's G7 summit in Naples, Russian officials held separate meetings with leaders of the G7 after the group's summits. This informal arrangement was dubbed the Political 8 (P8)—or, colloquially, the G7+1. At the invitation of UK Prime Minister Tony Blair and U.S. President Bill Clinton,[13] President Boris Yeltsin was invited first as a guest observer, later as a full participant. It was seen as a way to encourage Yeltsin with his capitalist reforms. Russia formally joined the group in 1998, resulting in the Group of Eight, or G8.

Focus of G8

editA major focus of the G8 since 2009 has been the global supply of food.[14] At the 2009 L'Aquila summit, the G8's members promised to contribute $22 billion to the issue. By 2015, 93% of funds had been disbursed to projects like sustainable agriculture development and adequate emergency food aid assistance.[15][16]

At the 2012 summit, President Barack Obama asked G8 leaders to adopt the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition initiative to "help the rural poor produce more food and sell it in thriving local and regional markets as well as on the global market".[17][18] Ghana became one of the first six African countries to sign up to the G8 New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition in 2012.[19] There was, however, almost no knowledge of the G8 initiative among some stakeholders, including farmers, academics and agricultural campaign groups. Confusion surrounding the plans was made worse, critics say, by "a dizzying array of regional and national agriculture programmes that are inaccessible to ordinary people".[20]

Russia's participation suspension (2014)

editOn 24 March 2014, the G7 members cancelled the planned G8 summit that was to be held in June of that year in the Russian city of Sochi, and suspended Russia's membership of the group, due to Russia's annexation of Crimea; nevertheless, they stopped short of outright permanent expulsion.[21] Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov downplayed the importance of the decision by the U.S. and its allies, and pointed out that major international decisions were made by the G20 countries.[22][3]

Later on, the Italian Foreign Affairs minister Federica Mogherini and other Italian authorities,[23][24] along with the EastWest Institute board member Wolfgang Ischinger,[25] suggested that Russia may restore its membership in the group. In April 2015, the German foreign minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier said that Russia would be welcomed to return to G8 provided the Minsk Protocol were implemented.[26] In 2016, he added that "none of the major international conflicts can be solved without Russia", and the G7 countries will consider Russia's return to the group in 2017. The same year, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzō Abe called for Russia's return to G8, stating that Russia's involvement is "crucial to tackling multiple crises in the Middle East".[27] In January 2017, the Italian foreign minister Angelino Alfano said that Italy hopes for "resuming the G8 format with Russia and ending the atmosphere of the Cold War".[28] On 13 January 2017, Russia announced that it would permanently leave the G8 grouping.[29] Nonetheless, Christian Lindner, the leader of Free Democratic Party of Germany and member of the Bundestag, said that Putin should be "asked to join the table of the G7" so that one could "talk with him and not about him", and "we cannot make all things dependent on the situation in Crimea".[6] In April 2018, the German politicians and members of the Bundestag Sahra Wagenknecht and Alexander Graf Lambsdorff said that Russia should be invited back to the group and attend the 2018 summit in Canada: "Russia should again be at the table during the [June] summit at the latest" because "peace in Europe and also in the Middle East is only possible with Russia".[7][30] The US President Donald Trump also stated that Russia should be reinstated to the group; his appeal was supported by the Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte.[8] After several G7 members quickly rejected US President Trump's suggestion to again accept the Russian Federation into the G8, Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov said that the Russian Federation wasn't interested in rejoining the political forum. He also said that the G20 is sufficient for the Russian Federation.[31] In the final statement of the 2018 meeting in Canada, the G7 members announced to continue sanctions and also to be ready to take further restrictive measures against the Russian Federation for the failure of Minsk Agreement complete implementation.[32][33]

A "new G8"

editOn June 11 2022, Vyacheslav Volodin, the current Chairman of the State Duma, announced on Telegram that "countries wishing to build an equal dialogue and mutually beneficial relations would actually form, together with Russia, a 'new G8'".[34] Although Volodin mentioned the group of eight countries not participating in the sanctions against the Russian Federation—China, India, Indonesia, Brazil, Mexico, Iran, and Turkey—there have been no updates regarding the new G8; however, four of the seven nations listed are already a part of, or are expected to join in 2024, BRICS.

Structure and activities

editBy design, the G8 deliberately lacked an administrative structure like those for international organizations, such as the United Nations or the World Bank. The group does not have a permanent secretariat, or offices for its members.

The presidency of the group rotates annually among member countries, with each new term beginning on 1 January of the year. The rotation order is: France, the United States, the United Kingdom, Russia (suspended), Germany, Japan, Italy, and Canada.[35] The country holding the presidency is responsible for planning and hosting a series of ministerial-level meetings, leading up to a mid-year summit attended by the heads of government. The president of the European Commission participates as an equal in all summit events.[36]

The ministerial meetings bring together ministers responsible for various portfolios to discuss issues of mutual or global concern. The range of topics include health, law enforcement, labor, economic and social development, energy, environment, foreign affairs, justice and interior, terrorism, and trade. There are also a separate set of meetings known as the G8+5, created during the 2005 Gleneagles, Scotland summit, that is attended by finance and energy ministers from all eight member countries in addition to the five "outreach countries" which are also known as the Group of Five—Brazil, People's Republic of China, India, Mexico, and South Africa.[37]

In June 2005, justice ministers and interior ministers from the G8 countries agreed to launch an international database on pedophiles.[38] The G8 officials also agreed to pool data on terrorism, subject to restrictions by privacy and security laws in individual countries.[39]

Global energy

editAt the Heiligendamm Summit in 2007, the G8 acknowledged a proposal from the EU for a worldwide initiative on efficient energy use. They agreed to explore, along with the International Energy Agency, the most effective means to promote energy efficiency internationally. A year later, on 8 June 2008, the G8 along with China, India, South Korea and the European Community established the International Partnership for Energy Efficiency Cooperation, at the Energy Ministerial meeting hosted by Japan holding 2008 G8 Presidency, in Aomori.[40]

G8 Finance Ministers, whilst in preparation for the 34th Summit of the G8 Heads of State and Government in Toyako, Hokkaido, met on the 13 and 14 June 2008, in Osaka, Japan. They agreed to the "G8 Action Plan for Climate Change to Enhance the Engagement of Private and Public Financial Institutions". In closing, Ministers supported the launch of new Climate Investment Funds (CIFs) by the World Bank, which will help existing efforts until a new framework under the UNFCCC is implemented after 2012. The UNFCCC is not on track to meeting any of its stated goals.[41]

In July 2005, the G8 Summit endorsed the IPHE in its Plan of Action on Climate Change, Clean Energy and Sustainable Development, and identified it as a medium of cooperation and collaboration to develop clean energy technologies.

Annual summit

editThe first G8 summit was held in 1997 after Russia formally joined the G7 group, and the last one was held in 2013. The 2014 summit was scheduled to be held in Russia. However, due to Crimea's annexation by the Russian Federation, the other seven countries decided to hold a separate meeting without Russia as a G7 summit in Brussels, Belgium.

Criticism

editOne type of criticism is that members of G8 do not do enough to help global problems, due to strict patent policy and other issues related to globalization. In Unraveling Global Apartheid, political analyst Titus Alexander described the G7, as it was in 1996, as the 'cabinet' of global minority rule, with a coordinating role in world affairs.[42]

In 2012 The Heritage Foundation, an American conservative think tank, criticized the G8 for advocating food security without making room for economic freedom.[43]

Relevance

editThe G8's relevance has been subject to debate from 2008 onward.[44] It represented the major industrialized countries but critics argued that the G8 no longer represented the world's most powerful economies, as China has surpassed every economy but the United States.[45]

Vladimir Putin did not attend the 2012 G8 summit at Camp David, causing Foreign Policy magazine to remark that the summit has generally outlived its usefulness as a viable international gathering of foreign leaders.[46] Two years later, Russia was suspended from the G8, then chose to leave permanently in January 2017.

The G20 major economies leaders' summit has had an increased level of international prestige and influence.[47] However, British Prime Minister David Cameron said of the G8 in 2012:[48]

Some people ask, does the G8 still matter, when we have a Group of 20? My answer is, yes. The G8 is a group of like-minded countries that share a belief in free enterprise as the best route to growth. As eight countries making up about half the world's gross domestic product, the standards we set, the commitments we make, and the steps we take can help solve vital global issues, fire up economies and drive prosperity all over the world.

Youth 8 Summit

editThe Y8 Summit or simply Y8, formerly known as the G8 Youth Summit[49] is the youth counterpart to the G8 summit.[50] The summits were organized from 2006 to 2013. The first summit to use the name Y8 took place in May 2012 in Puebla, Mexico, alongside the Youth G8 that took place in Washington, D.C. the same year. From 2016 onwards, similar youth conferences were organized under the name Y7 Summit.[51]

The Y8 Summit brings together young leaders from G8 nations and the European Union to facilitate discussions of international affairs, promote cross-cultural understanding, and build global friendships. The conference closely follows the formal negotiation procedures of the G8 Summit.[52] The Y8 Summit represents the innovative voice of young adults between the age of 18 and 35. At the end of the summit, the delegates jointly come up with a consensus-based[53] written statement, the Final Communiqué.[54] This document is subsequently presented to G8 leaders in order to inspire positive change.

The Y8 Summit was organized annually by a global network of youth-led organizations called The IDEA (The International Diplomatic Engagement Association).[55] The organizations undertake the selection processes for their respective national delegations, while the hosting country is responsible for organizing the summit. An example of such a youth-led organization is the Young European Leadership association, which recruits and sends EU Delegates.

The goal of the Y8 Summit is to bring together young people from around the world to allow the voices and opinions of young generations to be heard and to encourage them to take part in global decision-making processes.[56][57]

| Summit | Year | Host country | Location | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | International Student Model G8 | 2006 | Russia | Saint Petersburg |

| 2nd | Model G8 Youth Summit | 2007 | Germany | Berlin |

| 3rd | Model G8 Youth Summit | 2008 | Japan | Yokohama |

| 4th | G8 Youth Summit | 2009 | Italy | Milan |

| 5th | G8 Youth Summit | 2010 | Canada | Muskoka & Toronto |

| 6th | G8 Youth Summit | 2011 | France | Paris |

| ** | Y8 Summit | 2012 | Mexico | Puebla |

| 7th | G8 Youth Summit | 2012 | United States | Washington D.C. |

| 8th | Y8 summit | 2013 | United Kingdom | London |

| 9th | Y8 summit | 2014 | Russia | Moscow* |

* The Y8 Summit 2014 in Moscow was suspended due to the suspension of Russia from the G8.

See also

edit- D-8 Organization for Economic Cooperation

- Eight-Nation Alliance

- Forum for the Future (Bahrain 2005)

- G3 Free Trade Agreement

- G4 (EU)

- G-20 major economies

- Group of Two

- Group of Seven

- Group of Eleven

- Group of 15

- Group of 24

- Group of 30

- Junior 8

- List of countries by GDP (nominal)

- List of countries by military expenditures

- List of country groupings

- List of G8 leaders

- List of G8 summit resorts

- List of longest serving G8 leaders

- List of multilateral free-trade agreements

- North–South divide

- Western Bloc

- Great power

- World Social Forum

References

edit- ^ a b "The Group of Eight (G8) Industrialized Nations". CFR. Archived from the original on 15 November 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- ^ a b "Russia just quit the G8 for good". Independent.co.uk. 13 January 2017.

- ^ a b "U.S., other powers kick Russia out of G8". CNN.com. 24 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ Smale, Alison; Shear, Michael D. (24 March 2014). "Russia Is Ousted From Group of 8 by U.S. and Allies". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ^ "Russia suspended from G8 over annexation of Crimea, Group of Seven nations says". National Post. 24 March 2014. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ^ a b "FDP's push to invite Putin to G7 sows discord within possible German coalition". Reuters. 12 October 2017.

- ^ a b "G7 beraten über Syrien und die Ukraine". Deutsche Welle (in German).

- ^ a b "Trump calls for Russia to be invited to G8". Financial Times. 8 June 2018. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022.

- ^ Until recently, the EU had the privileges and obligations of a membership that did not host or chair summits. It was represented by the Commission and Council presidents. "EU and the G8". European Commission. Archived from the original on 26 February 2007. Retrieved 25 September 2007.

- ^ "Officials: G-20 to supplant G-8 as international economic council". CNN. 25 September 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- ^ "G20 to replace the G8". SBS. 26 September 2009. Archived from the original on 27 September 2009. Retrieved 26 September 2009.

- ^ "Japan and the G20: Ambivalence and the China factor". 11 February 2011.

- ^ Medish, Mark (24 February 2006). "Russia — Odd Man Out in the G-8", The Globalist. Retrieved 7 December 2008. Archived 5 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Cash-strapped G8 looks to private sector in hunger fight". Reuters. 18 May 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ DoCampo, Isabel (15 March 2017). "A Food-Secure Future: G7 and G20 Action on Agriculture and Food". The Chicago Council on Global Affairs. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ "L'Aquila Food Security Initiative | Tracking Support for the MDGS". iif.un.org. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ Tandon, Shaun (18 May 2012). "Obama turns to private sector to feed world's poor". Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 31 January 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ Patrick, Stewart M. (16 May 2012). "Why This Year's G8 Summit Matters". The Atlantic. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ "G8 Cooperation framework to support The "New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition" in Ghana" (PDF). Group of Eight Camp David.

- ^ "Ghana hopes G8 New Alliance will end long history of food insecurity". the Guardian. 18 February 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ "Ukraine crisis: Russia scathing about G8 suspension as fears grow". The Independent. 25 March 2014.

- ^ "Russia Temporarily Kicked Out Of G8 Club Of Rich Countries". Business Insider. 24 March 2014.

- ^ "Italy hopes G7 returns to G8 format – Foreign Ministry". ITAR-TASS. 8 June 2014.

- ^ "Italy working for Russia return to G8". ANSA. 3 July 2014.

- ^ "Amb. Wolfgang Ischinger Urges Inclusion of Russia in G8 | EastWest Institute". www.ewi.info. Archived from the original on 8 July 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- ^ "Russian return to G8 depends on Ukraine ceasefire-German minister". Reuters, 15 April 2015.

- ^ "Japan's Abe calls for Putin to be brought in from the cold". Financial Times. 17 January 2016.

- ^ "Italian Minister 'Hopes' For Russia's Return To G8". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 12 January 2017.

- ^ Tom Batchelor (13 January 2017). "Russia announces plan to permanently leave G8 group of industrialised nations after suspension for Crimea annexation". Independent.

- ^ "Wir brauchen auch Russland, um Probleme zu lösen". Deutschlandfunk (in German). 3 June 2018.

- ^ hermesauto (9 June 2018). "Russia brushes off possibility of G-8 return". The Straits Times.

- ^ Editorial, Reuters (9 June 2018). "The Charlevoix G7 Summit Communique". Reuters.

{{cite news}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ "G7 leaders ready to step up anti-Russian sanctions". TASS.

- ^ Chaya, Lynn. "Russia to form 'new G8' with Iran and China". NationalPost.com.

- ^ G8 Research Group. "What is the G8?". University of Toronto. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Japan): Summit Meetings in the Past; European Union: "EU and the G8" Archived 26 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "G5 Overview; Evolución del Grupo de los Cinco". Groupoffive.org. Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ "G8 to launch international pedophile database" David Batty 18 June 2005, The Guardian

- ^ "G8 to pool data on terrorism" Martin Wainwright, 18 June 2005, The Guardian

- ^ The International Partnership for Energy Efficiency Cooperation (IPEEC). 8 June 2008.

- ^ "G8 Finance Ministers Support Climate Investment Funds". IISD – Climate Change Policy & Practice. 14 June 2008. Archived from the original on 23 March 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ^ Alexander, Titus (1996). Unraveling Global Apartheid: An overview of world politics. Polity Press. pp. 212–213.

- ^ Miller, Terry (17 May 2012). "G8 Food Security Agenda Should Encourage Greater Privatisation". The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ Lee, Don (6 July 2008). "On eve of summit, G-8's relevance is unclear". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "China marches towards world's No. 2 economy". CNN. 16 August 2010.

- ^ Bremmer, Ian (14 May 2012). "Welcome to the New World Disorder". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- ^ Bosco, David (16 May 2012). "Three cheers for homogeneity". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- ^ Horgan, Colin (21 November 2012). "The G8 still matters: David Cameron". Ipolitics.ca. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ Bogott, Nicole (June 2010). "Global gerechte Handelspolitik". The European (in German). Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- ^ Dobson, Hugo (2011). "The G8, the G20, and Civil Society". In avona, Paolo; Kirton, John J.; Oldani, Chiara (eds.). Global Financial Crisis: Global Impact and Solutions. Ashgate. pp. 247, 251. ISBN 978-1409402725.

- ^ "Y7/Y8 and Y20 Summits". Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ^ Brun, Martine (July 2013). "Camille Grossetete, une Claixoise au Youth 8". Dauphiné Libéré (in French). Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- ^ Kohler, Oliver (July 2010). "Traumjob Bundeskanzlerin". Märkische Oderzeitung (in German). Archived from the original on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- ^ Castagna, Silvia (June 2013). "Da barista a ministro del G8 dei giovani". Il Giornale di Vicenza (in Italian).[permanent dead link]

- ^ "The President and CEO's Notebook: What is The IDEA?". Young Americans for Diplomatic Leadership. 22 April 2013. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ^ "ladý Slovák zastupoval Slovensko a EÚ na mládežníckom summite G20". www.teraz.sk. June 2012.

- ^ Enenkel, Kathrin (2009). G8 Youth Summit and Europe's Voice 2009: Results and Reflexions.

Further reading

edit- Bayne, Nicholas and Robert D. Putnam. (2000). Hanging in There: The G7 and G8 Summit in Maturity and Renewal. Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-1185-1; OCLC 43186692

- Haas, P.M. (1992). "Introduction. Epistemic communities and international policy coordination", International Organization 46, 1:1–35.

- Hajnal, Peter I. (1999). The G8 system and the G20: Evolution, Role and Documentation. Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9780754645504; OCLC 277231920

- Kokotsis, Eleonore. (1999). Keeping International Commitments: Compliance, Credibility, and the G7, 1988–1995. New York: Garland Publishing. ISBN 9780815333326; OCLC 40460131

- Reinalda, Bob and Bertjan Verbeek. (1998). Autonomous Policy Making by International Organizations. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-45085-7; OCLC 39013643

External links

edit- G8 Information Centre Archived 1 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine, G8 Research Group, University of Toronto

- "Special Report: G8", Guardian Unlimited

- "Profile: G8", BBC News

- "We are deeply concerned. Again", New Statesman, 4 July 2005, —G8 development concerns since 1977

- G8 Information Centre Finance Ministers Meetings

- "G8: Cooking the books won’t feed anyone", Oxfam International

- "Dear G8 Leaders, don’t lie about your aid", Oxfam Australia

- "Wait, the G-8 still exists?" Archived 27 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Foreign Policy Magazine

- "Is this the last G-8 summit meeting?" Archived 30 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Foreign Policy Magazine

- Chronique ONU | Le Conseil économique et social, Le Groupe des huit et le PARADOXE CONSTITUTIONNEL "The Group of Eight, ECOSOC and the Constitutional Paradox"

- No. of G8 Summit Protestors (1998–2015) Katapult-Magazin