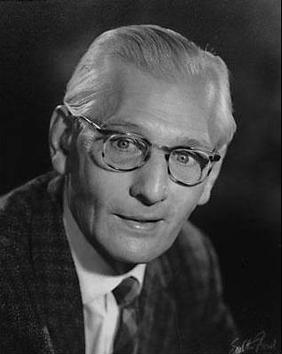

Charles Francis Christopher Hawkes, FBA, FSA (5 June 1905 – 29 March 1992) was an English archaeologist specialising in European prehistory. He was Professor of European Archaeology at the University of Oxford from 1946 to 1972.

Christopher Hawkes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Charles Francis Christopher Hawkes 5 June 1905 |

| Died | 29 March 1992 (aged 86) |

| Occupation | Archaeologist |

| Spouses | |

| Academic work | |

| Doctoral students | Tania Dickinson[1] Edward James (historian)[2] |

He was educated at Sandroyd School, Winchester College and New College, Oxford, where he obtained first class honours in classics. He began archaeological work at the British Museum, where he was Assistant Keeper in Pre-Historic and Romano-British Antiquities from 1928. In May 1946, Dr Hugh Fawcett took Hawkes some pieces from the newly discovered Mildenhall Treasure. It was Hawkes who identified them as late Roman silver.[3] He was appointed Professor of European Archaeology at Oxford later in 1946. He was a Fellow of Keble College. He was awarded the Gold Medal of the Society of Antiquaries in 1981,[4] now held by the Heberden Coin Room, Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.[5]

In 1933 he was married to Jacquetta Hopkins, with whom he co-authored Prehistoric Britain (1937); they divorced in 1953. He married Sonia Chadwick, also an archaeologist, in 1959.[6] They jointly edited Greeks, Celts and Romans: studies in venture and resistance, 1973.

He was survived by his wife Sonia and son, Nicholas.

Biography

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2023) |

Early life: 1905–1914

editHawkes' paternal family had been ironmasters in Birmingham, operating The Eagle Iron Foundry. His paternal grandfather Charles Samuel Hawkes moved to Beckenham in Kent with his seven children following the death of his wife; he later moved to South America, where he married again.[citation needed]

Hawkes' father, C. P. Hawkes, was raised in Kent, before studying history at Trinity College, Cambridge from 1894 to 1897. He travelled to the Canary Islands, where he met a woman who was half-Spanish and half-English, and they subsequently married, resulting in Hawkes' birth.[citation needed] C. P. Hawkes was also a published author.

Being schooled in London, Hawkes inherited his father's fascination with past societies, influenced in this by the scenery of southern England and what he had read in the works of Rudyard Kipling.[citation needed] When the First World War broke out in August 1914, Hawkes' father volunteered to join several friends in the Special Reserve of the Northumberland Fusiliers; he brought his family to Northumberland with him, where Christopher encountered archaeological and historical monuments in the North-East, such as Hadrian's Wall and Durham Cathedral.[citation needed]

Hawkes was a scholar at Winchester College between 1918 and 1924. Whilst at the College, he painted a frieze based on the Bayeux Tapestry.[7]

Personality

editAccording to Brian Fagan, Hawkes was "a complex character" and "an ardent and extremely skilled typologist".[8]

Selected works

edit- The Prehistoric Foundations of Europe To the Mycenean Age (Methuen, 1940)

- Saint Catherine's Hill Winchester (Proceedings of the Hampshire Field Club and Archaeological Society (Warren and Son Limited | The Wykeham Press, 1930)

- Duval, Paul-Marie ; Hawkes, Christopher (edited by), 'Celtic Art in Ancient Europe: Five Protohistoric Centuries. Proceedings of the Colloquy held in 1972 at the Oxford Maison Francaise' (Seminar Press, 1976)

- Hawkes, Christopher ; Dunning, G. C., 'The Belgae of Gaul and Britain' - bound offprint from Archaeological Journal LXXXVII [1930] pp. 150–335 and Index pp. 531–541. (Archaeological Journal, 1930)

- Hawkes, Christopher and Jacquetta, 'Prehistoric Britain' (Pelican Books / Penguin Books, 1952)

References

edit- ^ Dickinson, Tania (1976). The Anglo-Saxon burial sites of the upper Thames region, and their bearing on the history of Wessex, circa AD 400-700 (PhD). University of Oxford. p. xv. Archived from the original on 5 February 2023. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ James, Edward (1975). South-West Gaul from the fifth to the eighth century: the contribution of archaeology (PhD). University of Oxford.

- ^ Hobbs, Richard, "The Secret History of the Mildenhall Treasure", The Antiquaries Journal, Vol. 88, 2008, pp. 376 - 420

- ^ Harding (1992)

- ^ "Coin Details 131971". hcr.ashmus.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2 February 2024. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ Collectanea antiqua: essays in memory of Sonia Chadwick Hawkes was published in 2007

- ^ "Christopher F.C. Hawkes (1905-1992) – Winchester College". Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- ^ Fagan, Brian (2001). Grahame Clark: An Intellectual Biography of an Archaeologist. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. p. 177. ISBN 0-8133-3602-3.

Further reading

edit- Myres, J. N. L.; Hawkes, C. F. C.; Bruce-Mitford, Rupert; Hill, J. W. F. & Radford, C. A. Ralegh (1946). "The Archaeology of Lincolnshire and Lincoln: Anglian and Anglo-Danish Lincolnshire" (PDF). The Archaeological Journal. CIII. Royal Archaeological Institute: 85–101. doi:10.1080/00665983.1946.10853806.

- Daniel, Glyn Edmund; Chippindale, Christopher (1989) The Pastmasters: Eleven Modern Pioneers of Archaeology: V. Gordon Childe, Stuart Piggott, Charles Phillips, Christopher Hawkes, Seton Lloyd, Robert J. Braidwood, Gordon R. Willey, C. J. Becker, Sigfried J. De Laet, J. Desmond Clark, D.J. Mulvaney. New York: Thames and Hudson (hardcover, ISBN 0-500-05051-1).

- Harding, D. W. "Christopher Hawkes", in: The Record; 1992. Keble College; pp. 48–51

- Webster, Diana Bonakis (1991) "Hawkeseye": the early life of Christopher Hawkes. Stroud: Alan Sutton (hardcover, ISBN 0-86299-881-6

- Díaz-Andreu, Margarita, Megan Price and Chris Gosden 2009. "Christopher Hawkes, his archive and networks in British and European archaeology". The Antiquaries Journal 89: 1-22 Christopher Hawkes: his archive and networks in British and European archaeology; by Margarita Díaz-Andreu, & Megan Price[permanent dead link]