Amber Diceless Roleplaying Game

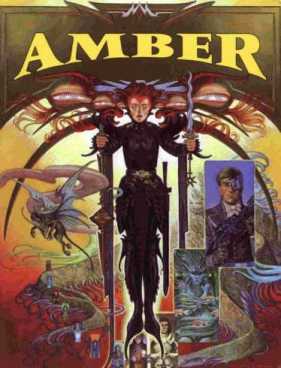

Cover of the main Amber DRPG rulebook (art by Stephen Hickman) | |

| Designers | Erick Wujcik |

|---|---|

| Publishers | Phage Press Guardians of Order |

| Publication | 1991 |

| Genres | Fantasy |

| Systems | Custom (direct comparison of statistics without dice) |

The Amber Diceless Roleplaying Game is a role-playing game created and written by Erick Wujcik, set in the fictional universe created by author Roger Zelazny for his Chronicles of Amber. The game is unusual in that no dice are used in resolving conflicts or player actions; instead a simple diceless system of comparative ability, and narrative description of the action by the players and gamemaster, is used to determine how situations are resolved.[1][2]

Amber DRPG was created in the 1980s, and is much more focused on relationships and roleplaying than most of the roleplaying games of that era.[1] Most Amber characters are members of the two ruling classes in the Amber multiverse, and are much more advanced in matters of strength, endurance, psyche, warfare and sorcery than ordinary beings. This often means that the only individuals who are capable of opposing a character are from his or her family, a fact that leads to much suspicion and intrigue.

History

[edit]Erick Wujcik wanted to design a role-playing game based on Amber for West End Games, and they agreed to look at his work. Wujcik intended to integrate the feel of the Amber setting from the novels into a role-playing game, and playtested his system for a few months at the Michigan Gaming Center where he decided to try it out as a diceless game. West End Games was not interested in a diceless role-playing game, so Wujcik acquired the role-playing game rights to Amber and offered the game to R. Talsorian Games, until he withdrew over creative differences. Wujcik then founded Phage Press, and published Amber Diceless Role-playing in 1991.[3]: 111–112

The original 256-page game book[4] was published in 1991 by Phage Press, covering material from the first five novels (the "Corwin Cycle") and some details – sorcery and the Logrus – from the remaining five novels (the "Merlin Cycle"), in order to allow players to roleplay characters from the Courts of Chaos. Some details were changed slightly to allow more player choice – for example, players can be full Trump Artists without having walked the Pattern or the Logrus, which Merlin says is impossible; and players' psychic abilities are far greater than those shown in the books.

A 256-page companion volume, Shadow Knight,[5] was published in 1993. This supplemental rule book includes the remaining elements from the Merlin novels, such as Broken Patterns, and allows players to create Constructs such as Merlin's Ghostwheel. The book presents the second series of novels not as additions to the series' continuity but as an example of a roleplaying campaign with Merlin, Luke, Julia, Jurt and Coral as the PCs. The remainder of the book is a collection of essays on the game, statistics for the new characters and an update of the older ones in light of their appearance in the second series, and (perhaps most usefully for GMs) plot summaries of each of the ten books. The book includes some material from the short story "The Salesman's Tale," and some unpublished material cut from Prince of Chaos,[citation needed] notably Coral's pregnancy by Merlin.

Both books were translated into French and published by Jeux Descartes in 1994 and 1995.

A third book, Rebma, was promised. Cover art was commissioned[6] and pre-orders were taken, but it was never published. Wujcik also expressed a desire to create a book giving greater detail to the Courts of Chaos.[7] The publishing rights to the Amber DRPG games were acquired in 2004 by Guardians of Order, who took over sales of the game and announced their intention to release a new edition of the game. However, no new edition was released before Guardians of Order went out of business in 2006. The two existing books are now out-of-print, but they have been made available as PDF downloads.[8]

In June 2007 a new publishing company, headed by Edwin Voskamp and Eleanor Todd, was formed with the express purpose of bringing Amber DRPG back into print. The new company is named Diceless by Design.[9]

In May 2010, Rite Publishing secured a license from Diceless by Design to use the rules system with a new setting in the creation of a new product to be written by industry and system veteran Jason Durall. The project Lords of Gossamer & Shadow (Diceless) was funded via Kickstarter in May 2013.[10] In Sept 2013 the project was completed, and on in Nov 2013 Lords of Gossamer and Shadow (Diceless) [11] was released publicly in full-color Print and PDF, along with additional supplements and continued support.

Setting

[edit]The game is set in the multiverse described in Zelazny's Chronicles of Amber. The first book assumes that gamemasters will set their campaigns after the Patternfall war; that is, after the end of the fifth book in the series, The Courts of Chaos, but uses material from the following books to describe those parts of Zelazny's cosmology that were featured there in more detail. The Amber multiverse consists of Amber, a city at one pole of the universe wherein is found the Pattern, the symbol of Order; The Courts of Chaos, an assembly of worlds at the other pole where can be found the Logrus, the manifestation of Chaos, and the Abyss, the source or end of all reality; and Shadow, the collection of all possible universes (shadows) between and around them. Inhabitants of either pole can use one or both of the Pattern and the Logrus to travel through Shadow.

It is assumed that players will portray the children of the main characters from the books – the ruling family of Amber, known as the Elder Amberites – or a resident of the Courts. However, since some feel that being the children of the main characters is too limiting, it is fairly common to either start with King Oberon's death before the book begins and roleplay the Elder Amberites as they vie for the throne; or to populate Amber from scratch with a different set of Elder Amberites. The former option is one presented in the book; the latter is known in the Amber community as an "Amethyst" game. A third option is to have the players portray Corwin's children, in an Amber-like city built around Corwin's pattern; this is sometimes called an "Argent" game, since one of Corwin's heraldic colours is Silver.

System

[edit]This section may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (May 2023) |

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2023) |

Attributes

[edit]Characters in Amber DRPG are represented by four attributes: Psyche, Strength, Endurance and Warfare.

- Psyche is used for feats of willpower or magic

- Strength is used for feats of strength or unarmed combat

- Endurance is used for feats of endurance

- Warfare is used for armed combat, from duelling to commanding armies

The attributes run from −25 (normal human level), through −10 (normal level for a denizen of the Courts of Chaos) and 0 (normal level for an inhabitant of Amber), upwards without limit. Scores above 0 are "ranked", with the highest score being ranked 1st, the next-highest 2nd, and so on. The character with 1st rank in each attribute is considered "superior" in that attribute, being considered to be substantially better than the character with 2nd rank even if the difference in scores is small. All else being equal, a character with a higher rank in an attribute will always win a contest based on that attribute.

The Attribute Auction

[edit]A character's ability scores are purchased during character creation in an auction; players get 100 character points, and bid on each attribute in turn. The character who bids the most for an attribute is "ranked" first and is considered superior to all other characters in that attribute. Unlike conventional auctions, bids are non-refundable; if one player bids 65 for psyche and another wins with a bid of 66, then the character with 66 is "superior" to the character with 65 even though there is only one bid difference. Instead, lower bidding characters are ranked in ascending order according to how much they have bid, the characters becoming progressively weaker in that attribute as they pay less for it. After the auction, players can secretly pay extra points to raise their ranks, but they can only pay to raise their scores to an existing rank. Further, a character with a bid-for rank is considered to have a slight advantage over character with a bought-up rank.

The Auction simulates a 'history' of competition between the descendants of Oberon for player characters who have not had dozens of decades to get to know each other. Through the competitive Auction, characters may begin the game vying for standings. The auction serves to introduce some unpredictability into character creation without the need to resort to dice, cards, or other randomizing devices. A player may intend, for example, to create a character who is a strong, mighty warrior, but being "outplayed" in the auction may result in lower attribute scores than anticipated, therefore necessitating a change of character concept. Since a player cannot control another player's bids, and since all bids are non-refundable, the auction involves a considerable amount of strategizing and prioritization by players. A willingness to spend as many points as possible on an attribute may improve your chances of a high ranking, but too reckless a spending strategy could leave a player with few points to spend on powers and objects. In a hotly contested auction, such as for the important attribute of warfare, the most valuable skill is the ability to force one's opponents to back down. With two or more equally determined players, this can result in a "bidding war," in which the attribute is driven up by increments to large sums. An alternative strategy is to try to cow other players into submission with a high opening bid. Most players bid low amounts between one and ten points in an initial bid in order to feel out the competition and to save points for other uses. A high enough opening bid could signal a player's determination to be first ranked in that attribute, thereby dissuading others from competing.

Psyche in Amber DRPG compared to the Chronicles

[edit]Characters with high psyche are presented as having strong telepathic abilities, being able to hypnotise and even mentally dominate any character with lesser psyche with whom they can make eye-contact. This is likely due to three scenes in the Chronicles: first, when Eric paralyzes Corwin with an attack across the Trump and refuses to desist because one or the other would be dominated; second, when Corwin faces the demon Strygalldwir, it is able to wrestle mentally with him when their gazes meet; and third, when Fiona is able to keep Brand immobile in the final battle at the Courts of Chaos.[12] However, in general, the books only feature mental battles when there is some reason for mind-to-mind contact (for example, Trump contact) and magic or Trump is involved in all three of the above conflicts, so it is not clear whether Zelazny intended his characters to have such a power; the combination of Brand's "living trump" powers and his high Psyche (as presented in the roleplaying game) would have guaranteed him victory over Corwin. Shadow Knight does address this inconsistency somewhat, by presenting the "living trump" abilities as somewhat limited.

Powers

[edit]Characters in Amber DRPG have access to the powers seen in the Chronicles of Amber: Pattern, Logrus, Shape-shifting, Trump, and magic.

- Pattern: A character who has walked the pattern can walk in shadow to any possible universe, and while there can manipulate probability.

- Logrus: A character who has mastered the Logrus can send out Logrus tendrils and pull themselves or objects through shadow.

- Shape-shifting: Shape-shifters can alter their physical form and abilities.

- Trump: Trump Artists can create Trumps, a sort of tarot card which allows mental communication and travel. The book features Trump portraits of each of the elder Amberites. The trump picture of Corwin is executed in a subtly different style – and has features very similar to Roger Zelazny's.

- Magic: Three types of magic are detailed: Power Words, with a quick, small effect; Sorcery, with pre-prepared spells as in many other game systems; and Conjuration, the creation of small objects.

Each of the first four powers is available in an advanced form.

Artifacts, Personal shadows and Constructs

[edit]While a character with Pattern, Logrus or Conjuration can acquire virtually any object, players can choose to spend character points to obtain objects with particular virtues – unbreakability, or a mind of their own. Since they have paid points for the items, they are a part of the character's legend, and cannot lightly be destroyed. Similarly, a character can find any possible universe, but they can spend character points to know of or inhabit shadows which are (in some sense) "real" and therefore useful. The expansion, Shadow Knight, adds Constructs – artifacts with connections to shadows.

Stuff

[edit]Unspent character points become good stuff – a good luck for the character. Players are also allowed to overspend (in moderation), with the points becoming bad stuff – bad luck which the Gamemaster should inflict on the character. Stuff governs how non-player characters perceive and respond to the character: characters with good stuff will often receive friendly or helpful reactions, while characters with bad stuff are often treated with suspicion or hostility.

As well as representing luck, stuff can be seen as representing a character's outlook on the universe: characters with good stuff seeing the multiverse as a cheerful place, while characters with bad stuff see it as hostile.

Conflict resolution

[edit]In any given fair conflict between two characters, the character with the higher score in the relevant attribute will eventually win. The key words here are fair and eventually – if characters' ranks are close, and the weaker character has obtained some advantage, then the weaker character can escape defeat or perhaps prevail. Close ranks result in longer contests while greater difference between ranks result in fast resolution. Alternatively, if characters' attribute ranks are close, the weaker character can try to change the relevant attribute by changing the nature of the conflict. For example, if two characters are wrestling the relevant attribute is Strength; a character could reveal a weapon, changing it to Warfare; they could try to overcome the other character's mind using a power, changing it to Psyche; or they could concentrate their strength on defense, changing it to Endurance. If there is a substantial difference between characters' ranks, the conflict is generally over before the weaker character can react.

The "Golden Rule"

[edit]Amber DRPG advises gamemasters to change rules as they see fit, even to the point of adding or removing powers or attributes.

Reception

[edit]Steve Crow reviewed Amber Diceless Roleplaying Game in White Wolf #31 (May/June, 1992), rating it a 4 out of 5 and stated that "It is undoubtedly a game for experienced gamers. While I would not recommend Amber to novices, it is a must buy for experienced gamemasters and players looking for new challenges."[13]

In the June 1992 edition of Dragon (Issue 182), both Lester Smith and Allen Varney published reviews of this game.

- Smith admired the professional production qualities of the 256-page rulebook, noting that because it was Smyth sewn in 32-page signatures, the book would always lie flat when opened. However, he found the typeface difficult to read, and the lack a coherent hierarchy of rules increased the reading difficulty as well. Smith admired the Attribute Auction and point-buy system for skills, and the focus on roleplaying in place of dice-rolling, but he mused that all of the roleplaying would mean "GMs have to spend quite a bit of time and creative effort coming up with wide-reaching plots for their players to work through. Canned, linear adventures just won't serve." He concluded by stating that the diceless system is not for every gamer: "As impressed as I am with the game, do I think it is the 'end-all' of role-playing games, or that diceless systems are the wave of the future? I'll give a firm “No” on both counts... However, I certainly do think that the Amber Diceless Roleplaying Game is destined for great popularity and a niche among the most respected of role-playing game designs."[14]

- Allen Varney thought the "Attribute Auction" to be "brilliant and elegant", but he wondered if character advancement was perhaps too slow to keep marginal players interested. He also believed that being a gamemaster would be "tough work. Proceed with caution." Varney recommended that players need some familiarity with the first five "Amber" novels by Zelazny. He concluded, "The intensity of the Amber game indicates [game designer Erik ] Wujcik is on to something. When success in every action depends on the role and not the roll, players develop a sense of both control and urgency, along with creativity that borders on mania."[14]

In Issue 65 of Challenge, Dirk DeJong had a good first impression of the game, especially the information provided about the Amber family members and their various flaws and strengths. However he found that "The biggest problem with this endeavor, and its downfall, is the nature of the conflict systems. First, they are diceless, really diceless, and don't involve any sort of random factors at all, aside from those that you can introduce by roleplaying them out. Thus, if you get involved with a character who's better than you at sword-fighting, even if only by one point out of 100, you're pretty much dead meat, unless you can act your way out." DeJong also disagreed with the suggestion that if the referee and players disagreed with a rule to simply remove it from the game. "I thought the entire idea of using rules and random results was to prevent the type of arguments that I can see arising from this setup." DeJong concluded on an ambivalent note, saying, "If you love Zelazny and the Amber series, jump on it, as this is the premier sourcebook for running an Amber campaign. [...] Personally, I just can't get turned on by a system that expects me to either be content with a simple subtraction of numbers to find out who won, or to describe an entire combat blow by blow, just so that I can attempt some trick to win."[15]

Loyd Blankenship reviewed Amber in Pyramid #2 (July/Aug., 1993), and stated that "Amber is a valuable resource to a GM - even if he isn't running an Amber game. For gamers who have an aspiring actor or actress lurking within their breast, or for someone running a campaign via electronic mail or message base, Amber should be given serious consideration."[16]

In his 2023 book Monsters, Aliens, and Holes in the Ground, RPG historian Stu Horvath noted, "There hasn't been an RPG quite like Amber, before or since. Bold though it was, the game didn't do very well commercially. The lack of dice became a flashpoint of controversy, with dice enthusiasts dramatically swearing off the game. That's a bit ridiculous, but it does get at a key hurdle Amber face: People like rolling dice. They've been doing it for thousands of years and a significant part of the appeal of RPGs is giving dice, often in sparkly colours, a toss."[17]

Community

[edit]Despite the game's out-of-print status, a thriving convention scene exists supporting the game.[18] Amber conventions, known as Ambercons, are held yearly in Massachusetts, Michigan, Portland (United States), Milton Keynes (England), Belfast (Northern Ireland) and Modena, Italy. Additionally, Phage Press published 12 volumes of a dedicated Amber DRPG magazine called Amberzine. Some Amberzine issues are still available from Phage Press.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Blankenship, Loyd (1993-08-01). "Pyramid Pick: Amber". Pyramid. #2. Retrieved 2008-02-15.

- ^ Lindroos, Nicole (2007). "Amber Diceless". In Lowder, James (ed.). Hobby Games: The 100 Best. Green Ronin Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-932442-96-0. OCLC 154694406.

- ^ Shannon Appelcline (2014). Designers & Dragons: The '90s. Evil Hat Productions. ISBN 978-1-61317-084-7.

- ^ Erick Wujcik Amber Diceless Roleplaying Game (Phage Press, 1991) ISBN 1-880494-00-0

- ^ Erick Wujcik Shadow Knight (Phage Press, 1993) ISBN 1-880494-01-9

- ^ Stephen Hickman's Rebma cover art

- ^ Blankenship, Loyd. "Shadow Knight (Preview) and Interview with Erick Wujcik". Pyramid. #6. Retrieved 2006-05-29.

- ^ Amber DRPG books at DriveThruRPG

- ^ "Amber Diceless Role-Playing - Official Website of Amber Diceless Role-Playing". dicelessbydesign.com.

- ^ "Lords of Gossamer & Shadow". Kickstarter. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ^ "Lords of Gossamer & Shadow". DrivethruRpg. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ Roger Zelazny The Great Book of Amber (Eos Press, 1999) ISBN 0-380-80906-0

- ^ Crow, Steve (May–June 1992). "Amber Diceless Roleplaying Game". White Wolf Magazine. No. 31. pp. 61–64.

- ^ a b Smith, Lester (June 1992). "Roleplaying Reviews". Dragon (182). TSR, Inc.: 97–99.

- ^ DeJong, Dirk (October 1992). "Challenge Reviews". Challenge. No. 65. p. 85.

- ^ "Pyramid: Pyramid Pick: Amber". www.sjgames.com.

- ^ Horvath, Stu (2023). Monsters, Aliens, and Holes in the Ground. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. p. 229. ISBN 9780262048224.

- ^ Torner, E.; White, W.J. (2014). Immersive Gameplay: Essays on Participatory Media and Role-Playing. McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-7864-9237-4. Retrieved 29 Jun 2023.

- Ranne, G.E. (July–August 1992). "Ambre". Casus Belli (70): 22–24. Review (in French)