Caesarea (Mazaca)

Mazaca | |

| |

| Location | Kayseri, Kayseri Province, Turkey |

|---|---|

| Region | Cappadocia |

| Coordinates | 38°43′21″N 35°29′15″E / 38.72250°N 35.48750°E |

| Type | Ancient Greek settlement |

| History | |

| Builder | Romans, Byzantines, Greeks |

| Abandoned | 11th century |

Caesarea (/ˌsɛzəˈriːə, ˌsɛsəˈriːə, ˌsiːzəˈriːə/; Greek: Καισάρεια, romanized: Kaisareia), also known historically as Mazaca (Greek: Μάζακα), was an ancient city in what is now Kayseri, Turkey. In Hellenistic and Roman times, the city was an important stop for merchants headed to Europe on the ancient Silk Road. The city was the capital of Cappadocia, and Armenian and Cappadocian kings regularly fought over control of the strategic city. The city was renowned for its bishops of both the Greek Orthodox and Armenian Apostolic churches.

After the Battle of Manzikert where the Byzantine Empire lost to the incoming Seljuk Empire, the city was later taken over by the Sultanate of Rum and became reconfigured over time with the influences of both Islamic and, later, Ottoman architecture.

History

[edit]Superseded trading town

[edit]

An earlier town or city associated with the Old Assyrian trade network can be traced to 3000 BCE, in ruined Kültepe, 20 km (12 mi) north-east. Findings there include numerous baked-clay tablets, some of which were enclosed in clay envelopes stamped with cylinder seals. The documents record common activities, such as trade between the Assyrian colony and the city-state of Assur and between Assyrian merchants and local people. The trade was run by families rather than the state. The Kültepe texts are the oldest documents of Anatolia. Although they are written in Old Assyrian, the Hittite loanwords and names in the texts are the oldest record of any Indo-European language.[1] Most of the archaeological evidence is typical of Anatolia rather than of Assyria, but the use of both cuneiform and the dialect is the best indication of Assyrian presence.

Hellenistic times

[edit]Caesarea remained as its precessor was a firmly inland trading centre firstly for many nearby city states, secondly due to links far beyond to east and west giving it, among regional comparators in size, enhanced trade.[2]

The city was the centre of a satrapy under Persian rule until it was conquered by Perdikkas, one of the generals of Alexander the Great when it became the seat of a transient satrapy by another of Alexander's former generals, Eumenes of Cardia. The city was subsequently passed to the Seleucid empire after the battle of Ipsus.

Kingdom of Cappadocia

[edit]It became the centre of an autonomous Greater Cappadocian kingdom under Ariarathes III of Cappadocia in around 250 BC. In the ensuing period, the city came under the sway of Hellenistic influence, and was given the Greek name of Eusebia (Greek: Εὐσέβεια) in honor of the Cappadocian king Ariarathes V Eusebes Philopator of Cappadocia (163–130 BC). The new name of Caesarea (Greek: Καισάρεια), by which it has since been known, was given to it by the last Cappadocian King Archelaus[3] or perhaps by Tiberius.[4]

Roman and Byzantine rule

[edit]The city passed under formal Roman rule in 17 AD. In the first century of Roman rule, the Caesarea belonged to the only four major cities in the region, together with Koloneia, Melitene and Tyana.[5] The city served as a imperial Roman mint factory and produced zinc and lead from mines of Delikkaya and Aladağ.[6]

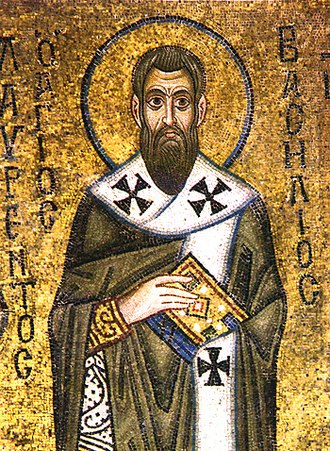

Caesarea was destroyed by the Sassanid king Shapur I after his victory over the Emperor Valerian I in 260 AD. At the time it was recorded to have around 40,000 inhabitants. The city gradually recovered, and became home to several early Christian saints: saints Dorothea and Theophilus the martyrs, Gregory of Nazianzus, Gregory of Nyssa, Basil of Caesarea, Andreas (Andrew) and Emmelia of Caesarea. In the 4th century, bishop Basil established an ecclesiastic centre in the suburbs, consisting of numerous charitable institutions (including a system of almshouses, an orphanage, old peoples' homes, and a leprosarium), monasteries and churches, that was later called Basileias.[7] The hypothesis that the modern city of Kayseri, situated about two miles from the site of Caesarea Mazaca, developed around this complex is not confirmed by archaeology.[8]

It was an important trading centre[2][9] on the Silk Road.

In the seventh century, the city became part of the Byzantine border region and became a target of the annual razzias the Arabs conducted into Anatolia. As such, it was besieged over 5 times between 646 and 738 and though it was sacked only once by Maslama ibn Abd al-Malik in 725/6, the attacks took a toll on the city and its surrounding.[10] The imperial authorities therefore made Caesarea an aplekton and tenth-century sources indicate arms production in the city.[11] Since the ninth century the city became also the administrative centre as the capital of the Byzantine Theme of Charsianon. Though the city lost most of its importance by the tenth century, is housed probably still around 50,000 people.[12] The city was sacked and the church of Basil pillaged and destroyed in 1067 by the Turks, symbolic for the collapse of Byzantine frontier.[13]

Kayseri Castle, built in antiquity, and expanded by the Seljuks and Ottomans, is still standing in good condition in the central square of the city.

Successor city

[edit]The city has some surviving buildings and is otherwise largely the foundations of what is now Kayseri, Turkey.[2] By the 1920, the foundations of a large cathedral church, used if not build in the tenth century, were the only trace of Byzantine Caesarea.[12]

Diocese of Caesarea

[edit]The diocese of Caesarea was the first of the churches of Asia Minor before the council of Chalcedon (451) and was considered an apostolic see. It possessed wide influence and authority over the diocese of Pontus and Armenia, and tradition held that Gregory the Illuminator had started from here his mission to Armenia.[14]

The city's bishop Eusebius, predecessor to Basil, likely presided over the Synod of Gangra.[14] Another bishop, Thalassius, attended the Second Council of Ephesus in 449 CE[15] and was suspended from the Council of Chalcedon in 451 CE.[16]

A Notitia Episcopatuum composed during the reign of Byzantine Emperor Heraclius in about 640 lists 5 suffragan dioceses of the metropolitan see of Caesarea. A 10th-century list gives it 15 suffragans.[17] In all the Notitiae Caesarea is given the second place among the metropolitan sees of the patriarchate of Constantinople, preceded only by Constantinople itself, and its archbishops were given the title of protothronos, meaning "of the first see" (after that of Constantinople). More than 50 first-millennium archbishops of the see are known by name, and the see itself continued to be a residential see of the Eastern Orthodox Church until 1923, when by order of the Treaty of Lausanne all members of that Church (Greeks) were deported from what is now Turkey.[18][19][20] Caesarea was also the seat of an Armenian diocese.[4]

No longer a residential bishopric, Caesarea in Cappadocia is today listed by the Catholic Church as a titular see of the Armenian Catholic Church and the Melkite Catholic Church.[21] It was a titular see of the Roman Church under various names as well, including Caesarea Ponti.

Gallery

[edit]-

Coin of Ariobarzanes, minted at Mazaca in 83 or 82 BC

-

Half-drachma from Caesarea (Mazaca) of Nero (reigned 37 to 68 CE)

-

The foundations of this building, Kayseri Castle / Fortress of Kayseri retains some city walls, both date to the Roman era

-

This sarcophagus of the Twelve Labors of Hercules at Kayseri Archaeology Museum dates to 150-160 CE

-

Cappadocian Greeks in Kayseri

-

House in Kayseri from an earlier period

-

Coin from Kayseri Archaeological Museum

-

Surp Kirkor Lusavoric Armenian Church dome and ceiling

-

Architectural style

References

[edit]- ^ Watkins, Calvert. "Hittite". In: The Ancient Languages of Asia Minor. Edited by Roger D. Woodard. Cambridge University Press. 2008. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-511-39353-2

- ^ a b c Borges, Jason (2020-02-18). "Caesarea Mazaca (Kayseri)". Cappadocia History. Retrieved 2021-09-04.

- ^ Everett-Heath, John (2005). "The Concise Dictionary of World Place-Names". Kayseri. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2007-12-11.

- ^ a b "Caesarea". Catholic Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2007-07-02.

- ^ Cooper & Decker 2012, p. 15.

- ^ Cooper & Decker 2012, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Cooper & Decker 2012, p. 30.

- ^ Caner, Daniel (2018). "Not a Hospital but a Leprosarium: Basil's Basilias and an Early Byzantine Concept of the Deserving Poor". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 72. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University: 25. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

- ^ "Silk Road Caravanserais in Central Turkey". Bob Cromwell: Travel, Linux, Cybersecurity. Retrieved 2021-09-04.

- ^ Cooper & Decker 2012, pp. 22–23, 242.

- ^ Cooper & Decker 2012, p. 242.

- ^ a b Cooper & Decker 2012, p. 31.

- ^ Cooper & Decker 2012, pp. 242, 252.

- ^ a b Cooper & Decker 2012, pp. 141–142.

- ^ Richard Price, Michael Gaddis The Acts of the Council of Chalcedon, Volume 1 p31.

- ^ Richard Price, Michael Gaddis, The Acts of the Council of Chalcedon, Volume 1 p36.

- ^ Heinrich Gelzer, Ungedruckte und ungenügend veröffentlichte Texte der Notitiae episcopatuum, in: Abhandlungen der philosophisch-historische classe der bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1901, p. 536, nº 77–82, and pp. 551–552, nnº 106–121.

- ^ Pius Bonifacius Gams, Series episcoporum Ecclesiae Catholicae Archived 2015-03-08 at Wikiwix, Leipzig 1931, p. 440

- ^ Michel Lequien, Oriens christianus in quatuor Patriarchatus digestus, Paris 1740, Vol. I, coll. 367–390

- ^ Raymond Janin, v. 2. Césarée de Cappadoce, in Dictionnaire d'Histoire et de Géographie ecclésiastiques, vol. XII, Paris 1953, coll. 199–203

- ^ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 867

Bibliography

[edit]- Cooper, Eric; Decker, Michael J. (24 July 2012). Life and Society in Byzantine Cappadocia. Springer. ISBN 978-1-137-02964-5. Retrieved 6 December 2024.