History of the English monarchy

The history of the English monarchy covers the reigns of English kings and queens from the 9th century to 1707. The English monarchy traces its origins to the petty kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England, which consolidated into the Kingdom of England by the 10th century. Anglo-Saxon England had an elective monarchy, but this was replaced by primogeniture after the Norman Conquest in 1066. The Norman and Plantagenet dynasties expanded their authority throughout the British Isles, creating the Lordship of Ireland in 1177 and conquering Wales in 1283.

The monarchy's gradual evolution into a constitutional and ceremonial monarchy is a major theme in the historical development of the British constitution.[1] In 1215, King John agreed to limit his own powers over his subjects according to the terms of Magna Carta. To gain the consent of the political community, English kings began summoning Parliaments to approve taxation and to enact statutes. Gradually, Parliament's authority expanded at the expense of royal power.

The Crown of Ireland Act 1542 granted English monarchs the title King of Ireland. In 1603, the childless Elizabeth I was succeeded by James VI of Scotland, known as James I in England. Under the Union of the Crowns, England and the Kingdom of Scotland were ruled by a single sovereign while remaining separate nations. For the history of the British monarchy after 1603, see History of monarchy in the United Kingdom.

Anglo-Saxons (800s–1066)

[edit]Anglo-Saxon government

[edit]

The origins of the English monarchy lie in the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain in the 5th and 6th centuries. In the 7th century, the Anglo-Saxons consolidated into seven kingdoms known as the Heptarchy. At certain times, one king was strong enough to claim the title bretwalda (Old English for "over-king"). In the 9th and 10th centuries, the kings of Wessex united the separate kingdoms into a single Kingdom of England.[3]

In theory, all governing authority resided with the king. He alone could make Anglo-Saxon law, mint coins, levy taxes, raise the fyrd, or make foreign policy. In reality, kings needed the support of the English church and the nobility to rule.[4] A monarch's rule was not legitimate unless he received coronation by the church. Coronation consecrated a king, giving him priest-like qualities and divine protection. The coronation of Edgar the Peaceful (r. 959–975) served as a model for future British coronations.[5][6]

The king governed in consultation with the witan, the council of bishops, ealdormen, and thegns he chose to advise him.[7] The witan also elected new kings from among male royal family members (æthelings). Primogeniture was not the definitive rule governing succession, so strong candidates replaced weak ones.[8]

While the capital was at Winchester, the king traveled with his itinerant court from one royal vill to another as they collected food rent and heard petitions. The king's income came from revenue from the royal demesne (now known as the Crown Estate), judicial fines, and taxation of trade. The geld (land tax) was also an essential source of revenue.[9]

House of Wessex

[edit]

After 865, Viking invaders conquered all the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms except for Wessex, which survived due to the leadership of Alfred the Great (r. 871–899). Alfred absorbed Kent and western Mercia and was the first to style himself "king of the Anglo-Saxons".[10][11] Alfred's son, Edward the Elder (r. 899–924), continued to recover and consolidate control over the other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. Only the Kingdom of York and Northumbria remained in Viking hands at his death. Edward's sons completed the reconquest of these holdouts.[12]

Edward's son Æthelstan (r. 924–939) first used the title "king of the English" and is considered the founder of the English monarchy.[13] He died childless, and his younger half-brother Edmund I (r. 939–946) succeeded him. After Edmund's murder, his two young sons were passed over in favor of their uncle, Eadred (r. 946–955). He never married and raised his nephews as his heirs. The eldest, Eadwig (r. 955–959), succeeded his uncle, but the younger brother Edgar (r. 959–975) was soon declared king of Mercia and the Danelaw. Eadwig's death prevented civil war, and Edgar the Peaceful became the undisputed king of all England in 959.[14]

Edgar was succeeded by his eldest son, Edward the Martyr (r. 975–978). His younger brother, Æthelred the Unready (r. 978–1016), had him murdered and then became king. The Danes began raiding England in the 990s, and Æthelred resorted to buying them off with ever more expensive payments of Danegeld. Æthelred's marriage to Emma of Normandy deprived the Danes of a place to shelter before crossing the Channel. Still, it did not prevent Swein Forkbeard, king of Denmark, from conquering England in 1013.[15]

After Swein died in 1014, the English invited Æthelred to return from exile if he agreed to address complaints against his earlier rule, including high taxes, extortion, and the enslavement of free men. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records this agreement, which historian David Starkey called "the first constitutional settlement in English history".[16] Æthelred died in 1016, and his son Edmund Ironside became king. Swein's son Cnut invaded England and defeated Edmund at the Battle of Assandun. Afterward, the two divided England, with Edmund ruling Wessex and Cnut taking the rest.[17]

Cnut the Great and his sons

[edit]

After Ironside's death, Cnut (r. 1016–1035) became king of all England and quickly married Æthelred's widow, Emma of Normandy. Cnut united England with the kingdoms of Denmark and Norway in what historians call the North Sea Empire. Because Cnut was not in England for much of his reign, he divided England into four parts (Wessex, East Anglia, Mercia, and Northumbria). He appointed trusted earls to rule each region. The creation of large earldoms covering multiple shires necessitated the office of sheriff or "shire reeve". The sheriff was the king's direct representative in the shire. He oversaw the shire court and collected taxes and royal estate dues.[18]

Earl Godwin of Wessex was the strongest earl and Cnut's chief minister. When Cnut died in 1035, rival sons contended for the throne: Emma's son Harthacnut (then in Denmark) and Ælfgifu's son Harold Harefoot (in England). Godwin supported Harthacnut, but Leofric, earl of Mercia, backed Harold.[19] In a compromise, Harold became king of Mercia and Northumbria, while Harthacnut became king of Wessex. Harold died in 1040, and Harthacnut ruled a reunited England until he died in 1042.[17]

Some members of the House of Wessex saw Cnut's death as a chance to regain power. Æthelred's youngest son, Alfred Aetheling, returned to England but was captured, blinded, and died of his injuries in 1037.[20]

Edward the Confessor

[edit]

Edward the Confessor (r. 1042–1066) was the only surviving son of Æthelred and Emma. In 1041, Harthacnut recalled his half-brother from exile in Normandy. When he died without heirs, the forty-year-old Edward was the natural successor. He had spent most of his life in Normandy and was "probably more French than English" culturally.[21]

As king, Edward invited his nephew, Edward the Exile, to return to England. Edward died before reaching England, but his son Edgar Ætheling and daughter Margaret were able to return. Margaret would marry Malcolm III of Scotland.[20]

By this time, the Anglo-Saxon government had become sophisticated.[22] Edward appointed the first chancellor, Regenbald, who kept the king's seal and oversaw the writing of charters and writs. The treasury had developed into a permanent institution by this time as well.[23] London was becoming the political and commercial capital of England. Edward furthered this transition by building Westminster Palace and Westminster Abbey.[24]

Despite his government's sophistication, Edward had much less land and wealth than Earl Godwin and his sons. In 1066, the Godwinson estates were worth £7,000, while the king's estates were worth £5,000.[25] To counter the power of the Godwinsons, Edward created a French party loyal to him. He made his nephew, Ralph of Mantes, the earl of Hereford. He overturned the election of a Godwin relative to be Archbishop of Canterbury and appointed Robert of Jumièges instead. In 1051, Edward's brother-in-law, Count Eustace of Boulogne, visited England and initiated a quarrel with Godwin. Ultimately, Edward had the entire Godwinson family outlawed and forced into exile.[26]

Around this time, Edward invited his relative William, duke of Normandy, to England. According to Norman sources, the king nominated William as his heir. However, Edward's favouritism towards the French was unpopular with the English people. With popular support, Godwin returned to England in 1052. Edward had to restore the Godwinsons to their former lands. This time, Edward's French supporters were outlawed.[27]

Harold Godwinson

[edit]The childless Edward the Confessor died on 5 January 1066. His fifteen-year-old great-nephew, Edgar Ætheling, had the strongest claim to the throne. Nevertheless, Harold Godwinson, earl of Wessex and leader of the powerful Godwin family, claimed Edward promised him the throne. Popular with the people and the Witan,[28] Harold was quickly crowned at Westminster Abbey on 6 January, the same day and place Edward was buried.[29]

William of Normandy disputed Harold's succession. William was the great-nephew of Emma of Normandy, wife of two English kings. He married Matilda of Flanders, a direct descendant of Alfred the Great. William claimed he was Edward's designated heir and prepared to invade England with the blessing of Pope Alexander II.[30] Before William reached England, King Harald Hardrada of Norway invaded with Tostig Godwinson, the exiled brother of Harold Godwinson. Harold defeated Hardrada at the Battle of Stamford Bridge on 25 September 1066.[31]

Meanwhile, William landed in England on 28 September. He fought Harold at the Battle of Hastings on 14 October. It was a disaster for the English. Harold and his brothers Gyrth, the earl of East Anglia, and Leofwine, the earl of Kent, were killed. Ealdred, archbishop of York, nominated Edgar Ætheling to be king, and this was supported by the leaders of London and the earls Morcar and Edwin.[32]

Edgar was never crowned, and English resistance soon collapsed. Edgar and the English leadership submitted to William, and the Norman conqueror was crowned king on Christmas Day 1066 at Westminster Abbey.[33]

Normans (1066–1154)

[edit]

Norman government

[edit]After the Norman Conquest, the kings of England were, as dukes of Normandy, nominal vassals to the kings of France. For the next centuries, the English monarchy would be deeply involved with French politics, and English kings usually spent most of their time in France.[34]

The king claimed ownership of all land in England.[note 1] The lands of the old Anglo-Saxon nobility were confiscated and distributed to a French-speaking Anglo-Norman aristocracy according to the principles of feudalism.[36][37] The king gave fiefs to his barons who in return owed the king fealty and military service.[38]

The Normans preserved the basic system of English government. The Witan's role of consultation and advice was continued by the curia regis (Latin for "king's court").[37] During crown-wearings held three times a year, the king met with all his bishops and barons in the magnum concilium (Latin for "great council"). These councils were generally dominated by the king, and it is unclear if these were truly deliberative bodies.[39] The local shire and hundred courts continued to exist as well.[40]

The Norman kings designated nearly a third of England as royal forests (i.e. royal hunting preserves).[41] The forest provided kings with food, timber, and money. People paid the king for rights to graze cattle or cut down trees. A system of forest law developed to protect the royal forests. Forest law was unpopular because it was arbitrary and infringed on the property rights of other landholders. A landholder's right to hunt deer or farm his land was limited if it fell within the royal forest.[42]

William the Conqueror

[edit]

It took nearly five years of fighting before the Norman Conquest of England was secure. Across England, the Normans built castles for defence as well as intimidation of the locals. In London, William ordered construction of the White Tower, the central keep of the Tower of London. Once finished, the White Tower "was the most imposing emblem of monarchy that the country had ever seen, dwarfing all other buildings for miles around."[43]

At times, there was tension between the monarch and his Norman vassals, who were used to French models of government in which royal power was much weaker than in England. The 1075 Revolt of the Earls was defeated by the king, but the monarchy continued to resist forces of feudal fragmentation.[44]

The church was critical to William's conquest of England. In 1066, it owned between 25 and 33 per cent of all land,[45] and appointment to bishoprics and abbacies were important sources of royal patronage. Pope Alexander II supported the Norman invasion because he wanted William to oversee church reform and to remove unfit bishops. William forbade ecclesiastical cases (those involving marriage, wills, and legitimacy) from being heard in secular courts; jurisdiction was handed over to church courts. But William also tightened royal control over the church. Bishops were banned from traveling to Rome, and royal permission was needed to enact new canon law or to excommunicate a noble.[46][47]

Henry I

[edit]

The death of William I in 1087 illustrates the absence of any firm rules of succession. William gave Normandy to his oldest son, Robert Curthose, while his second son, William II or "Rufus" (r. 1087–1100), was given England.[48] Between 1098 and 1099, the Great Hall at Westminster Palace, the king's main residence, was built. It was one of the largest secular buildings in Europe, and a monument to the Anglo-Norman monarchy.[49]

On 2 August 1100, Rufus was killed while hunting in the New Forest. His younger brother, Henry I (r. 1100–1135), was hastily elected king by the barons at Winchester on August 3 and crowned king at Westminster Abbey on August 5, just three days after his brother's death. At the coronation, Henry not only promised to rule well; he renounced the unpopular policies of his brother and promised to restore the laws of Edward the Confessor. This oath was written down and distributed throughout England as the Coronation Charter, which was reissued by all future 12th-century kings and was incorporated into Magna Carta.[50][51]

During Henry's reign, the royal household was formalised. It was divided into the chapel in charge of royal documents (which evolved into the chancery), the chamber in charge of finances, and the master-marshal in charge of travel (the court remained itinerant during this period). The household also included several hundred mounted household troops. The office of justiciar—effectively the king's chief minister—developed out of the need for a viceroy when the king was in Normandy and was mainly concerned with royal finance and justice.[52] Under the first justiciar, Roger of Salisbury, the Exchequer was established to manage royal finances.[53] Royal justice became more accessible with the appointment of local justices in each shire and itinerant justices traveling judicial circuits of multiple shires.[54] Historian Tracy Borman summarised the impact of Henry I's reforms as "transform[ing] medieval government from an itinerant and often poorly organised household into a highly sophisticated administrative kingship based on permanent, static departments."[55]

In 1106, Henry defeated and captured his eldest brother Robert II, Duke of Normandy, a failed claimant to the throne, at Battle of Tanchebray; William Clito son of Robert escaped.[56]

Henry married Matilda of Scotland, the niece of Edgar the Ætheling. This marriage was widely seen as uniting the House of Normandy with the House of Wessex and produced two children, Matilda (who married Holy Roman Emperor Henry V in 1114) and William Adelin (a Norman-French variant of Ætheling).[57] But in 1120, England was thrown into a succession crisis when William Adelin died in the sinking of the White Ship.[58] In 1126, Henry I made a controversial decision to name his daughter Empress Matilda (his only surviving legitimate child) his heir and forced the nobility to swear oaths of allegiance to her. William Clito tried to raise his cause but he was killed in 1128; in the same year, the widowed Matilda married Geoffrey of Anjou, and the couple had three sons in the years 1133–1136.[59] Robert died captive in 1134, predeceased Henry I by one year.[60]

Stephen

[edit]Despite the oaths sworn to her, Matilda was unpopular both for being a woman and because of her marriage ties to Anjou, Normandy's traditional enemy.[61] Following Henry's death in 1135, his nephew, Stephen of Blois (r. 1135–1154), laid claim to the throne and took power with the support of most of the barons. Matilda challenged his reign; as a result, England descended into a period of civil war known as the Anarchy (1138–1153). While Stephen maintained a precarious hold on power, he was ultimately forced to compromise for the sake of peace. Both sides agreed to the Treaty of Wallingford by which Stephen adopted Matilda's son, Henry FitzEmpress, as his son and heir.[62]

Plantagenets (1154–1399)

[edit]Henry II

[edit]

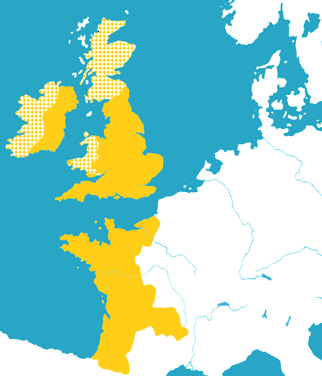

On December 19, 1154, Henry II (r. 1154–1189) became the first king of a new dynasty, the House of Plantagenet. He was also the first king crowned King of England rather than King of the English. Henry founded the Angevin Empire, which controlled almost half of France including Normandy, Anjou, Maine, Touraine, and the Duchy of Aquitaine.[63]

Henry's first task was restoring royal authority in a kingdom fractured by years of civil war. In some parts of the country, nobles were virtually independent of the Crown. In 1155, Henry expelled foreign mercenaries and ordered the demolition of illegal castles. He also dealt quickly and effectively with rebellious lords, such as Hugh de Mortimer.[64]

Henry's legal reforms had a profound impact on English government for generations. In earlier times, English law was largely based on custom. Henry's reign saw the first official legislation since the Conquest in the form of Henry's various assizes and the growth of case law.[65][66] In 1166, the Assize of Clarendon established the supremacy of royal courts over manorial and ecclesiastical courts.[67] Henry's legal reforms also transformed the king's personal role in the judicial process into an impersonal legal bureaucracy. The 1176 Assize of Northampton divided the kingdom into six judicial circuits called eyres allowing itinerant royal judges to reach the whole kingdom.[68] In 1178, the king ordered five members of his curia regis to remain at Westminster and hear legal cases full time, creating the Court of King's Bench. Writs (standardised royal orders with the great seal attached) were developed to deal with common legal problems. Any freeman could purchase a writ from the chancery and receive royal justice without the king's personal intervention.[69] For example, a writ of novel disseisin commanded a local jury to determine whether someone had been unjustly dispossessed of land.[68]

Since William the Conqueror's separation of secular and ecclesiastical jurisdiction, church courts claimed exclusive authority to try clergy, including monks and clerics in minor orders. The most contentious issue was "criminous clerks" accused of theft, rape or murder. Church courts could not impose the death penalty or bodily mutilation, and their punishments (penance and defrocking) were lenient. In 1164, Henry issued the Constitutions of Clarendon, which required criminous clerks who had been defrocked to be handed over to royal courts for punishment as laymen. It also forbade appeals to the pope. Archbishop Thomas Becket opposed the Constitutions, and the Becket controversy culminated in his murder in 1170. In 1172, Henry reached a settlement with the church in the Compromise of Avranches. Appeals to Rome were allowed, and secular courts were given jurisdiction over clerics accused of non-felony crimes.[70][71]

Henry also extended his authority outside of England. In 1157, he invaded Wales and received the submission of Owain of Gwynedd and Rhys ap Gruffydd of Deheubarth.[72] The Scottish king William the Lion was forced to acknowledge the English king as feudal overlord[note 2] in the Treaty of Falaise.[74] The 1175 Treaty of Windsor confirmed Henry as feudal overlord of most of Ireland.[75]

Richard the Lionheart

[edit]

Upon Henry's death, his eldest surviving son Richard I (r. 1189–1199), nicknamed the Lionheart, succeeded to the throne. As king, he spent a total of six months in England.[76] In 1190, the king left England with a large army and fleet to join the Third Crusade to reconquer Jerusalem from Saladin. Richard funded this campaign through taxation (such as the Saladin tithe) as well as selling offices, titles, and land.[77] In his absence, England was governed by William de Longchamp, in whom was consolidated both secular and ecclesiastical power as justiciar, chancellor, Bishop of Ely, and papal legate.[78]

Concerned that his younger brother John would usurp power while he was on Crusade, Richard made his brother swear to leave England for three years. John broke his oath and was in England by April 1191 leading opposition against Longchamp. From Sicily, Richard sent Archbishop Walter de Coutances to England as his envoy to resolve the situation. In October, a group of barons and bishops led by the Archbishop deposed Longchamp. John was appointed regent, but real power was exercised by Coutances as justiciar.[79]

While returning from Crusade, Richard was imprisoned by Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI for over a year and was not released until England paid an enormous ransom.[80] In 1193, John defected to Philip II of France, and the two plotted to take Richard's lands on the Continent.[81] After a four-year absence, Richard returned to England in March 1194, but he soon left again to wage war against Philip II, who had overrun the Vexin and parts of Normandy.[82] By 1198, Richard had reconquered most of his territory. At the Battle of Gisors, Richard adopted the motto Dieu et mon droit (French for "God and my Right"), which was later adopted as the royal motto.[83] In 1199, Richard died from wounds received while besieging Châlus-Chabrol. Before his death, the king made peace with John, naming him his successor.[84]

John

[edit]

At Westminster Abbey in May 1199, John (r. 1199–1216) was crowned Rex Angliae (Latin for "King of England") rather than the older form of Rex Anglorum (Latin for "King of the English").[85]

John captured Arthur I, Duke of Brittany, a claimant to the throne as son of John's deceased elder brother Duke Geoffrey II and former heir to Richard in 1202, and presumably murdered him in 1203; he also placed Arthur's sister Eleanor, Fair Maid of Brittany under house arrest.[86]

In 1204, John lost Normandy and his other Continental possessions. The remainder of his reign was shaped by attempts to rehabilitate his military reputation and fund wars of reconquest.[87] Traditionally, the king was expected to fund his government out of his own income derived from the royal demesne, profits of royal justice, and profits from the feudal system (such as incidents, reliefs, and aids). In reality, this was rarely possible, especially in time of war.[88]

To fund his campaigns, John imposed a "thirteenth" (8 per cent) tax on revenues and movable goods that would become the model for taxation through the Tudor period. The king also raised money by charging high court fees and—in the opinion of his barons—abusing his right to feudal incidents and reliefs.[89] Scutages were levied almost annually, much more often than under earlier kings. In addition, John showed partiality and favouritsm when dispensing justice. This and his paranoia caused his relationship with the barons to break down.[90]

After quarreling with the king over the election of a new Archbishop of Canterbury, Pope Innocent III placed England under papal interdict in 1208. For the next six years, priests refused to say mass, officiate marriages, or bury the dead. John responded by confiscating church property.[91] In 1209, the pope excommunicated John, but he remained unrepentant. It was not until 1213 that John reconciled with the pope, going so far as to convert the Kingdom of England into a papal fief with John as the pope's vassal.[92]

The Anglo-French War of 1213–1214 was fought to restore the Angevin Empire, but John was defeated at the Battle of Bouvines. The military and financial losses of 1214 severely weakened the king, and the barons demanded that he govern according to Henry I's Coronation Charter. On 5 May 1215, a group of barons renounced their fealty to John calling themselves the Army of God and the Holy Church and chose Robert Fitzwalter to be their leader.[note 3] The rebels numbered about 40 barons together with their sons and vassals. The other barons—around a hundred—worked with Archbishop Langton and the papal legate Guala Bicchieri to effect compromise between the two sides.[94] Over a month of negotiations resulted in Magna Carta (Latin for "Great Charter"), which was formally agreed to by both sides at Runnymede on 15 June. This document defined and limited the king's powers over his subjects. It would be reconfirmed throughout the 13th century and gain the status of "inalienable custom and fundamental law".[95] Historian Dan Jones notes that:

Whereas many of the clauses in the charter were formal terms pertaining to specific policies pursued by John—whether with regard to raising armies, levying taxes, impeding merchants, or arguing with the Church—the most famous clauses aimed at a deeper elaboration of the rights of subjects to set out the limits of central government. Clause 39 reads: "No free man shall be taken or imprisoned or disseised or outlawed or exiled or in any way ruined ... except by lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land." Clause 40 is more laconic: "To no one will we sell, to no one will we deny or delay right or justice." These clauses addressed the whole spirit of John's reign and by extension the spirit of kingship itself. For the eleven years in which John had resided in England, his barons had tasted a form of tyranny. John had used his powers in an arbitrary, partisan, and exploitative fashion and had used the processes of law deliberately to weaken and menace his noble lords. He had broken the spirit of kingship as presented by Henry II back in 1153, when he traveled the country offering unity and legal process to all.[96]

Unlike earlier charters of liberties, Magna Carta included an enforcement mechanism in the form of a council of 25 barons who were permitted to wage "lawful rebellion" against the king if he violated the charter. The king had no intention of adhering to the document and appealed to Pope Innocent who annulled the agreement and excommunicated the rebel barons. This began the First Barons' War, during which the rebels offered the crown to Philip II's son, the future Louis VIII of France.[note 4] By June 1216, Louis had taken control of half of England, including London. While he had not been crowned, he was proclaimed King Louis I at St Paul's Cathedral, and many English nobles along with King Alexander II of Scotland gave him homage. In the midst of this collapse of royal authority, John died abruptly at Newark Castle on 19 October.[98]

Henry III

[edit]

After John's death, loyal barons and bishops took his nine-year-old son to Gloucester Abbey where he was crowned Henry III (r. 1216–1272) in a rushed coronation. This established the precedent that the eldest son became king regardless of age.[99] Henry was the first child king since Æthelred the Unready,[100] and William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke, served as regent until his death in 1219. Marshal led royal forces to victory against the rebel barons and French invaders at the Battles of Lincoln and Sandwich in 1217.[101] While the claim of Eleanor was ignored, she remained under house arrest.[102]

During Henry's reign, the principle that kings were subject to the law gained acceptance.[103] To build support for the new king, his government re-issued Magna Carta in 1216 and 1217 (along with the Charter of the Forest).[104] In January 1225, Magna Carta was re-issued at a Great Council in return for approval of a tax to fund military campaigns in France. This established a new constitutional precedent in which "military expeditions would be financed at the expense of detailed concessions of political liberties".[105] In 1236, Henry began calling such meetings Parliament. By the 1240s, these early Parliaments had not only assumed power to grant taxes but were also venues where nobles could complain about government policy or corruption.[106]

In 1227, Henry was eighteen years old, and the regency officially ended. Yet, throughout his personal rule the king displayed a tendency to be dominated by foreign favourites. After the fall of the justiciar Hubert de Burgh in 1230, Bishop Peter des Roches became the king's chief minister. While holding no great office himself, the bishop showered his Poitevin relation Peter de Rivaux with a large number of offices.[107] He was placed in charge of the treasury, the privy seal, and the royal wardrobe. At the time, the wardrobe was a department that was at the centre of financial and political decisions in the royal household. He was given financial control of the royal household for life, was keeper of the forests and ports, and was, in addition, the sheriff of twenty-one counties. Rivaux used his immense power to enact important administrative reforms.[108] Nevertheless, the accumulation of power by foreigners led Richard Marshal to open rebellion. The bishops as a group threatened Henry with excommunication, which finally made him strip the Poitevin party of power.[109]

Eleanor of Brittany died in 1241 under a long imprisonment, and her claim was only posthumously recognized by several chronicles; [102]with Geoffrey leaving no descendants, Henry III became the hereditary heir of the royal family.

Henry then transferred his favouritism to his Lusignan half-brothers, William and Aymer de Valence. By the 1250s, there was widespread resentment against the Lusignans. There was also opposition to the "Sicilian business", Henry's unrealistic plans to conquer the Kingdom of Sicily for his second son, Edmund Crouchback. In 1255, the king informed Parliament that as part of the Sicilian campaign he owed the pope the huge sum of £100,000 (equal to £157,233,010 today) and that if he defaulted England would be placed under an interdict. By 1257, there was a growing consensus that Henry was unfit to rule.[110][111][112]

In 1258, the king was forced to submit to a radical reform programme promulgated at the Oxford Parliament. The Provisions of Oxford transferred royal power to a council of fifteen barons. A parliament would meet three times a year and appoint all royal officers (from justiciar and chancellor to sheriffs and bailiffs). The new government's leader was Simon de Montfort, the king's brother-in-law and former friend. By the terms of the 1295 Treaty of Paris, the English Crown gave up all claims to Normandy and Anjou in return for keeping the Duchy of Aquitaine as a vassal of the French king.[113]

When the king tried to overturn the Provisions of Oxford, Montfort led a rebellion, the Second Barons' War. In 1265, Montfort called a Parliament to consolidate support for the rebellion. For the first time, knights of the shire and burgesses from the important towns were summoned along with barons and bishops. Simon de Montfort's Parliament was an important milestone in the evolution of Parliament. Montfort was killed at the Battle of Evesham in 1265, and royal authority was restored.[114]

In 1268, Henry III ordered the Amesbury Priory to commemorate both Arthur and Eleanor in commemoration of past kings and queens as well.[115]

Henry traveled less than past kings. As a consequence, he spent large amounts of money on royal palaces. His most expensive projects were the rebuilding of Westminster Palace and Abbey, costing £55,000 (equal to £52,395,588 today). He spent a further £9,000 (equal to £8,573,824 today) on the Tower of London.[116][112] Westminster Abbey alone nearly bankrupted the king.[117]

Henry III died in 1272, having been king for fifty-six years. His turbulent reign was the third longest of any English monarch.[114]

Edward I

[edit]

Edward I (r. 1272–1307), nicknamed Longshanks for his height, was in Italy when he learned that his father had died. Previous monarchs were only legally recognised as king after coronation, but Edward's reign officially began on 20 November, the same day his father was buried at Westminster Abbey. Walter Giffard, archbishop of York; Roger Mortimer, a marcher lord; and Robert Burnell were appointed regents. A proclamation issued on 23 November stated:[119]

The government of the realm has come to the king on the death of King Henry his father, by hereditary succession and by the will of the magnates of the realm and by their fealty done to the king, wherefore the magnates have caused the king's peace to be proclaimed in the king's name.

Edward returned to England in August 1274 determined to restore royal authority. His first act was ordering the Hundred Rolls survey, a detailed investigation into what rights and land the Crown had lost since Henry III's reign. It was also intended to root out corruption by royal officials, and while few people were prosecuted for wrongdoing, it sent a message that Edward was a reformer.[120]

From his father's reign, Edward learned the importance of building national consensus for his policies through Parliament, which he usually summoned twice a year at Easter and Michaelmas. Edward effected his reform program through a series of parliamentary statutes: Statute of Westminster of 1275, Statute of Gloucester of 1278, Statute of Mortmain of 1279, Statute of Acton Burnell of 1283, and Statute of Westminster of 1285. In 1297, he reissued Magna Carta.[121][122] In 1295, Edward summoned the Model Parliament, which included knights and burgesses to represent the counties and towns. These "middle earners" were the most important group of taxpayers, and Edward was eager to gain their financial support for an invasion of Scotland.[123]

Through effective management of Parliament, Edward was able to fund his military campaigns in Wales and Scotland. He successfully and permanently conquered Wales, built impressive castles to enforce English domination, and brought the country under English law with the Statute of Wales. In 1301, the king's eldest son, Edward of Caernarfon, was created Prince of Wales and given control of the Principality of Wales. The title continues to be granted to the heirs of British monarchs.[125]

The death of Alexander III of Scotland in 1286 and his granddaughter Margaret of Norway in 1290 left the Scottish throne vacant. The Guardians of Scotland recognised Edward's feudal overlordship and invited him to adjudicate the Scottish succession dispute. In 1292, John Balliol was chosen Scotland's new king, but Edward's brutal treatment of his northern vassal led to the First War of Scottish Independence. In 1307, Edward died on his way to invade Scotland.[126]

Edward II

[edit]At his coronation, Edward II (r. 1307–1327) promised not only to uphold the laws of Edward the Confessor as was traditional but also "the laws and rightful customs which the community of the realm shall have chosen".[127] Edward thus abandoned any claim to absolute power and recognised the need to rule in cooperation with Parliament.[128] The new king inherited problems from his father: the Crown was in debt and the war in Scotland was going badly. He compounded these problems by alienating the nobility. The main cause of conflict was the influence wielded by royal favourites.[129]

The king's reliance on favourites proved a convenient scapegoat for the barons, who blamed unpopular policies on them rather than directly oppose the king.[130] When Parliament met in April 1308, Henry de Lacy, Earl of Lincoln, and a delegation of nobles presented the Declaration of 1308, which for the first time explicitly distinguished between the king as a person and the Crown as an institution to which the people owed allegiance. This distinction was known as the doctrine of capacities.[131]

In 1310, Parliament complained that "the state of the king and the kingdom had much deteriorated since the death of the elder King Edward ... and the whole kingdom had been not a little injured".[132] Specifically, Edward was accused of being guided by evil counselors, impoverishing the Crown, violating Magna Carta, and losing Scotland. The magnates elected twenty-one ordainers to reform the government. The completed reforms were presented to Edward as the Ordinances in August 1311. Like Magna Carta and the Provisions of Oxford, the Ordinances of 1311 were an attempt to limit the powers of the monarch. It banned the practice of purveyance and going to war without consulting Parliament. Government revenue was to be paid to the exchequer rather than to the royal household, and Parliament was to meet at least once a year. Parliament was to create committees to investigate royal abuses and to appoint royal ministers and officials (such as the chancellor and county sheriffs).[133]

The Ordinances also required the exile of the king's favourite, Piers Gaveston. By January 1312, Edward had publicly repudiated the ordinances, and Gaveston was back in England.[134] Earl Thomas of Lancaster, the king's cousin, led a group of magnates that captured and executed Gaveston.[note 5] This act nearly plunged England into civil war but negotiations restored an uneasy peace.[136]

After Gaveston's death, the most influential men around the king were Hugh Despenser and his son, Hugh Despenser the Younger. The king alienated moderate barons by dispensing royal patronage without parliamentary approval as required by the Ordinances and allowing the Despensers to act with impunity. In 1318, negotiations led to the Treaty of Leake in which the king agreed to abide by the Ordinances of 1311. A permanent royal council was created with eight bishops, four earls, and four barons as members.[137]

Edward's favouritsm toward the Despensers continued to destabilize the kingdom. The Despensers had become the gatekeepers to the king, and their enemies "were liable to be deprived of land or possessions or else thrown into prison".[138] The Welsh Marches were particularly destabilized by Hugh the Younger's accumulation of land. In 1321, a group of marcher lords invaded the Despenser estates, beginning the Despenser War.[139] Edward defeated the baronial opposition in 1322 and overturned the Ordinances.[140] For the next few years, Edward ruled as a tyrant. The author of the Vita Edwardi Secundi wrote of this period,[141]

parliaments, colloquies, and councils decide nothing these days. For the nobles of the realm, terrified by threats and the penalties inflicted on others, let the king's will have free play. Thus today will conquers reason. For whatever pleases the king, though lacking in reason, has the force of law.

In 1324, Edward's wife Isabella and their son, Prince Edward, traveled to France on a diplomatic mission. While there, the Queen formed an alliance with Roger Mortimer, a marcher lord who had fought against Edward in the Despenser War. At the head of a mercenary army, they invaded England in 1326. Important noblemen defected to the Queen's cause, and London rose in revolt. Meanwhile, the King and the Dispensers fled to Wales. On October 26, Isabella and Mortimer proclaimed that in the King's absence power temporarily resided with the fourteen-year-old Prince Edward. Having been abandoned by most of his household, the King was captured on 16 November.[142]

By this point, it was clear that Edward II could not remain king, but this precipitated a constitutional crisis as there was no legal process to remove a crowned and anointed king who in theory was the source of all public authority.[143] At the Parliament of 1327, the Articles of Accusation were drawn up accusing the King of violating his coronation oath and following the advice of evil councilors. On 20 January, Edward II was forced to abdicate. This marked the first time in English history that a monarch was formally deposed from the throne. The former king died on 21 September, probably murdered on the orders of his wife.[144][145]

Edward III

[edit]

Five days after his father's abdication, the fourteen-year-old Edward III (r. 1327–1377) was crowned king, but it was Isabella and Mortimer who truly held power. Under their three-year rule, the monarchy was weakened abroad and at home. They made a disadvantageous treaty with France and failed to press Edward's claim to the French throne when his uncle, Charles IV, died without a male heir. They also agreed to the Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton, which forfeited England's claim to overlordship of Scotland. At home, Mortimer used his new power to enrich himself even as the Crown faced bankruptcy and the nation experienced a rise in crime and violence. In 1330, Mortimer had Edmund of Woodstock, the King's uncle, arrested and executed for treason.[147]

On 19 October 1330, the seventeen-year-old Edward staged a coup at Nottingham Castle with the help of William Montagu and around 16 other young household companions. Mortimer was arrested, tried before Parliament, and executed for treason.[148] The young King, now in full control of his kingdom, realised that he could not afford to alienate the English nobility. He cultivated "an aristocratic culture, which bound the king and nobles together."[149] In particular, royal-noble bonds were strengthened through frequent tournaments in which Edward himself would take part.[150] Edward was the first king since the Conquest to speak English, and during his reign Middle English began to replace French as the language of the aristocracy.[151]

In 1333, Edward invaded Scotland winning a major victory at the Battle of Halidon Hill due to the use of the English longbow.[152] The victory allowed Edward to place Edward Balliol on the Scottish throne with himself as overlord. With French help, the Scots loyal to David II continued to resist English interference in the Second War of Scottish Independence.[153]

In March 1337, Edward created six new earldoms in order to gain military support for a war against France. His eldest son, the six-year-old Edward of Woodstock, was made Duke of Cornwall, the first duchy created in England. In May 1337, King Philip VI of France confiscated the Duchy of Aquitaine and the County of Ponthieu from the English king. In 1340, Edward claimed the French throne on the grounds that he was the last male descendant of his grandfather, Philip IV of France. To symbolise his claim, the King added the fleur-de-lis to the royal arms of England.[154][155]

In 1346, Edward invaded France in pursuit of his claim, setting off the Hundred Years' War which would last until 1453. The English won the Battle of Crécy and after a siege took the town of Calais, which would remain an English possession for the next two centuries. After a successful campaign in France, Edward returned to England and founded the Order of the Garter at Windsor Castle in 1348.[156] Between 1350 and 1377, Edward spent £50,000 (equal to £49,984,568 today)[112] transforming Windsor from an ordinary castle into a "palatial castle of quite extraordinary splendour".[157]

The King's eldest son Edward, known to history as the Black Prince, won the Battle of Poitiers in 1356 in which the French king John II was captured.[151] In the Treaty of Brétigny of 1360, Edward renounced his claims to the French throne and was awarded outright sovereignty over Calais, Ponthieu, and Aquitaine. Edward also negotiated a peace with Scotland that included the release of David II in return for recognising the English king's overlordship of Scotland.[158]

Edward worked with Parliament to build consensus and support for his wars and, in the process, furthered Parliament's development as an essential institution of government. According to historian David Starkey,[159]

Edward was willing to do whatever was necessary to persuade members of Parliament to dig their hands deep into their constituents' pockets. It meant doing deals, greasing palms, slapping backs. Edward's victories were reported in detail; Parliament was consulted on war diplomacy and ratified the peace treaties with France ... The length of Edward's wars also normalized taxation. Direct taxation, on income and property, continued to be voted only for war. But indirect taxation on trade became permanent, enhancing royal power and extending the scope of royal government.

There were a number of setbacks in the last years of Edward's reign. The new French king Charles V successfully drove the Black Prince out of Aquitaine. Prince Edward returned to England in 1371 bankrupt and in declining health possibly caused by dysentery. The infirmity of both the elderly King and Prince Edward created a power vacuum that the King's younger son, John of Gaunt, tried to fill; nevertheless, there were many complaints of corruption and mismanagement in government. In the Good Parliament of 1376, the House of Commons refused to finance the war with France until corrupt ministers and Alice Perrers, the royal mistress, were removed. Having little choice, the King acquiesced and the accused ministers were arrested and brought to trial before Parliament in the first impeachment proceedings. While the Good Parliament was still in session, the Black Prince died at the age of 45.[160]

Edward's new heir was his nine-year-old grandson Richard of Bordeaux. There were concerns that Richard's uncles might usurp power. To strengthen the boy's position, he was recognised in Parliament as heir apparent and given the titles of prince of Wales, duke of Cornwall, and earl of Chester. Having secured the succession, Edward III died in 1377.[161]

Richard II

[edit]

Richard II (r. 1377–1399) was ten years old when he became king. Despite the king's youth, no regency was set up to govern during his minority since his uncle John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster (the most likely candidate for regent) was unpopular. Instead, Richard theoretically ruled in his own right with the advice of a 12-member advisory council. In reality, the government was dominated by the king's uncles, especially Gaunt, and courtiers, such as Simon Burley, Guichard d'Angle, and Aubrey de Vere.[162][163] In 1381, resentment over poll taxes led to the Peasants' Revolt. The fourteen-year-old king's brave and decisive leadership in ending the revolt demonstrated he was ready to assume actual power. But the revolt also left a deep impression on Richard, "convincing him that disobedience, no matter how justified, constituted a threat to order and stability within his realm and must not be tolerated."[164]

After the revolt, Parliament appointed Michael de la Pole to advise the King. Pole proved himself a loyal servant and was made chancellor in 1383 and earl of Suffolk in 1385. The King's most important favourite, however, was Robert de Vere, the earl of Oxford. In 1385, de Vere was given the novel title of marquess and placed above all earls and below only the royal dukes in rank. In 1386, de Vere was made duke of Ireland, the first duke not of royal blood. This favouritism alienated other aristocrats, including the King's uncles.[165][166]

Another cause for complaint was the situation in France. The English retained only Calais and a small part of Gascony while French ships harassed English traders in the Channel. Richard personally led an invasion of Scotland in 1385 that achieved nothing. Meanwhile, he spent lavishly on palace renovations and court entertainments.[167] One historian described Richard's government as "a high-tax, high-spend, cliquey affair."[168]

In 1386, Pole requested additional funds to defend England against a potential French invasion, but under the leadership of Richard's uncle Thomas of Woodstock, the Wonderful Parliament refused to act until Pole was removed as chancellor.[169] Richard refused at first but gave in after being threatened with deposition. A council was set up to audit royal finances and exercise royal authority. At 19 years old, the King was once again reduced to a figurehead.[170] Defiant, Richard left London for a "gyration" (tour) of the country to gather an army.[171]

Richard returned to London in November 1387 and was approached by three nobles: his uncle Thomas, duke of Gloucester; Richard Fitzalan, earl of Arundel; and Thomas Beauchamp, earl of Warwick. These Lords Appellant (as they became known) appealed (or indicted) Pole, de Vere, and other close associates of the King with treason.[172] The Lords Appellant defeated Richard's army at the Battle of Radcot Bridge, and the King had no choice but to submit to their wishes. At the Merciless Parliament of 1388, Richard's favourites were convicted of treason.[169]

After the royal favourites had been removed, the Lords Appellant were content. In 1389, Richard resumed royal authority and reconciled with John of Gaunt, who used his influence on Richard's behalf.[174] For a time, Richard ruled well. The King led a successful expedition to Ireland in 1394 and negotiated a 28-year truce with France in 1396.[175] In July 1397, Richard was finally ready to move against his enemies. The three Lords Appellant were arrested. When Parliament met at Westminster, the presence of 300 of Richard's Cheshire archers made it clear that no dissent would be tolerated. Chancellor Edmund Stafford, bishop of Exeter, preached the opening sermon on Ezekiel 37:22, "There shall be one king over them all".[176] The Lords Appellant were then tried and found guilty of treason.[177]

For the next two years, Richard ruled as a tyrant, using extortion to gain forced loans from his subjects.[178] The twice-married king was childless and the succession was uncertain. The man with the strongest claim was John of Gaunt, whose son and heir was Henry Bolingbroke.[177] In 1397, a dispute between Bolingbroke and Thomas Mowbray led to the former's banishment from England for 10 years.[179] When John of Gaunt died in 1399, Richard confiscated the Duchy of Lancaster and extended Bolingbroke's banishment for life.[180]

In May 1399, Richard embarked on a second invasion of Ireland, taking most of his followers with him. Bolingbroke returned to England in July with a small force of men but quickly gained the support of powerful nobles, such as Henry Percy, the earl of Northumberland and most powerful man in northern England.[181][182] Richard returned to England, but his army and supporters rapidly melted away. By 2 September, Richard was a prisoner in the Tower.[180]

On 30 September, an assembly of the House of Lords and House of Commons met in Westminster Hall (later referred to as a convention parliament, it technically was not a parliament because it met without royal authority). Richard Scrope, archbishop of York, stated that Richard, who was not present, had agreed to abdicate. When Thomas Arundel, archbishop of Canterbury, asked if the Lords and Commons accepted this each lord agreed and the Commons shouted their agreement.[183] Thirty-nine articles of deposition were read out in which Richard was charged with breaking his coronation oath and violating "the rightful laws and customs of the realm".[184] After John Trevor, bishop of St. Asaph, announced Richard's deposition, Bolingbroke gave a speech claiming the Crown. The archbishops of Canterbury and York each took one of Bolingbroke's arms and seated him on the empty throne to shouts of acclimation from the Lords and Commons.[185]

Richard II was not the first English monarch to be deposed; that distinction belongs to Edward II. Edward abdicated in favor of his son and heir. In Richard's case, the line of succession was deliberately broken by Parliament. Historian Tracy Borman writes that this "created a dangerous precedent and made the crown fundamentally unstable."[186]

Lancastrians (1399–1461)

[edit]Henry IV

[edit]

Bolingbroke was crowned as Henry IV (r. 1399–1413) two weeks after Richard II's deposition. His dynasty was known as the House of Lancaster, a reference to his father's title Duke of Lancaster. As part of the coronation, Henry created Knights of the Bath, a tradition that was repeated at all later coronations. He was also the first English monarch to be crowned on the Stone of Scone, which Edward I had taken from Scotland.[187]

In January 1400, the Epiphany Rising unsuccessfully tried to free Richard and restore him to the throne. Henry realized he would have no security as long as Richard lived, so he ordered his death, most likely by starvation.[188] Henry's reign was forever tarnished by the deposition and murder of an anointed king, and he constantly had to fight off plots and rebellions. In 1400, the Welsh Revolt began, and Henry Hotspur of the powerful Percy family joined the revolt in 1403. Hotspur was defeated at the Battle of Shrewsbury, but King Henry continued to face challenges to his legitimacy.[189]

When overthrowing Richard, Henry had promised to reduce taxation, and Parliament held him to that promise, refusing to raise taxes even as the king went into debt fighting defensive wars. Financially, Henry benefited from inheriting the vast Lancastrian estates of his father. He decided to administer these lands separately from the crown lands.[190] The practice of holding the Duchy of Lancaster separate from the crown estate was continued by later monarchs.

Charles VI of France, Richard's father-in-law, refused to recognise Henry. The French revived their claims to Aquitaine, attacked Calais, and aided the Welsh Revolt. But in 1407, the Armagnac–Burgundian Civil War divided France, and the English were keen to take advantage of French disunity. English policy vacillated toward the opposing sides as King Henry supported the Armagnac faction, while his eldest son, Henry of Monmouth, supported the Burgundian faction. As the king's health declined, Monmouth assumed a greater role in government, and there were suggestions that the king should abdicate in favor of his son.[191]

Henry V

[edit]

Abdication became unnecessary when Henry IV died in 1413, and Monmouth became King Henry V (r. 1413–1422). He escaped the troubles of his father's reign by making conciliatory gestures toward his father's enemies. He also removed the taint of usurpation by honoring the deceased Richard II and giving him a royal re-burial at Westminster Abbey.[191]

As a result of his unifying gestures, Henry V's reign was largely free from domestic strife, leaving the king free to pursue the last phase of the Hundred Years' War with France. The war appealed to English national pride,[192] and Parliament readily granted a double subsidy to finance the campaign, which began in August 1415. In this first campaign, Henry won a legendary victory at the Battle of Agincourt.[193] The triumphant king returned home to a jubilant nation eager to support further wars of conquest. Parliament gave the king lifetime duties on wine imports and other tax grants. When he was ready to return to France, Parliament granted another double subsidy.[194]

In 1419, he conquered Normandy—the first time an English king ruled Normandy since King John lost it in 1204.[195] In 1420, the Treaty of Troyes recognised Henry as heir and regent of the incapacitated King Charles VI of France. The new peace was sealed by Henry's marriage to the French princess Catherine of Valois. Charles's son, the Dauphin, was disinherited by the treaty; however, he continued to assert his right to the French throne and remained in control of over half of France south of the Loire river.[196]

Henry V was a popular king who restored royal authority and lowered crime. Despite high taxes, England prospered under Henry V. He kept his personal expenses low and managed royal finances well.[197] But Henry's frequent absences from England did create difficulties. While in France, Henry insisted on dealing with petitions from Parliament personally despite the long distances and delays involved. By 1420, the House of Commons was complaining, and funds for further wars in France were more difficult to secure. On 31 August 1422, the king fell ill and died while on another campaign in France.[196]

Henry VI

[edit]

Only nine months old when his father died, Henry VI (1st r. 1422–1461; 2nd r. 1470–1471) was the youngest to inherit the Crown. His grandfather, Charles VI of France, died on 21 October 1422. Under the terms of the Treaty of Troyes, the infant Henry became the dual monarch of England and France.[198] In his will, Henry V made his brother John, duke of Bedford, regent of France. His other brother Humphrey, duke of Gloucester, was made regent in England. Gloucester, however, was a poor statesman and distrusted by his peers. Instead of sole regent, he became lord protector[note 6] and governed alongside a regency council .[200]

On 29 July 1429, Charles VII was crowned King of France at Reims Cathedral in a clear violation of the Treaty of Troyes. In response, the eight-year-old Henry was quickly crowned at Westminster on 5 November. Parts of the French coronation service were added to emphasise Henry's claim to the French throne.[201] In April 1430, the young king traveled to France for his second coronation. Traditionally, French monarchs were crowned at Reims Cathedral. For security reasons, Henry received coronation at Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris on 16 December 1431.[202]

Bedford died in 1435, and the regency government ended in 1437.[200] Henry was pious, generous, and forgiving but also indecisive. He was the opposite of his warrior father and the first monarch since the Conquest never to command an army.[204] While he enjoyed the trappings of kingship (holding many crown-wearing ceremonies and participating in royal touch rituals), Henry depended on others to run the government. Initially, this responsibility fell to his uncle Gloucester and great-uncle Cardinal Henry Beaufort.[205] Later, the King replaced them with William de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk,[206] whose abuses of power and heavy spending inspired intense opposition.[207]

While never surrendering his claim to be King of France, Henry attempted to make peace with Charles VII. In 1445, he married Margaret of Anjou, the niece of Queen Marie of France. Unlike her husband, Margaret took an active interest in government affairs.[208] The English always disliked politically active queens and suspected Margaret of advancing French interests.[209]

Suffolk had supported the unpopular peace policy and marriage. To improve his popularity, he reversed course and resumed hostilities with France. By September 1449, the English had lost all of Normandy. Parliament reacted by impeaching Suffolk in February 1450.[210] It charged him with impoverishing the Crown and plotting the King's death. To protect his favourite, the King banished Suffolk, who was subsequently murdered while boarding a ship.[211] Popular outrage over maladministration led to Jack Cade's Rebellion. Henry fled London and left Margaret to restore the peace.[212]

In August 1450, Edmund Beaufort, duke of Somerset, returned from France. Somerset served as governor of Normandy, and many blamed him for its loss. Nevertheless, he quickly became Henry's new favourite and chief minister. Around the same time, Richard, duke of York, returned from serving as lieutenant of Ireland and became the leader of the opposition against Somerset. These two men were potential heirs of the childless king. Like Henry, Somerset descended from Edward III's third surviving son, John of Gaunt. York's mother descended from Gaunt's older brother, Lionel, duke of Clarence, and his father descended from Gaunt's younger brother, Edmund, duke of York.[213] York's maternal ancestry arguably gave him a better claim to the throne than Henry himself.[212]

In July 1453, the French conquered Gascony, ending 300 years of English rule and the Hundred Years War.[212] Henry had lost all of his French inheritance except for Calais.[206] This event probably precipitated his mental breakdown in August. In October, Margaret gave birth to a son named Prince Edward, and she attempted to rule for her incapacitated husband. However, Parliament made York lord protector in March 1454. Despite the King's recovery at Christmas 1454, York refused to give up power. In May 1455, the Yorkists fought royal forces at the Battle of St Albans, traditionally considered the start of the Wars of the Roses (1455–1487).[214]

At the parliament of October 1460, York submitted his claim to the throne, which rested on the argument that Richard II's rightful heir was York's uncle, Edmund Mortimer. Therefore, all three Lancastrian kings had reigned unlawfully.[215] However, the House of Lords declined to sanction Henry's deposition. Instead, it decided that Henry would remain king but recognise York as his heir . While Henry seemed to accept this, Margaret refused to agree to her son's disinheritance and continued fighting.[216]

After York died in 1460, his son Edward IV continued to assert his claim. In March 1461, the nineteen-year-old Edward entered London, and a hastily convened Yorkist-dominated council declared him king. He was crowned at Westminster Abbey on 4 March. Henry and Margaret fled to Scotland with their son. In 1465, Henry was captured and imprisoned in the Tower of London.[217][216]

Yorkists (1461–1485)

[edit]Edward IV

[edit]

Edward IV (1st r. 1461–1470; 2nd r. 1471–1483) owed the throne mainly to the support of his cousin, Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick. After the Yorkist victory, Warwick became the King's chief minister. However, the two men did not always agree on policy. Warwick favored an alliance with France and was negotiating with Louis XI for Edward's marriage to a French princess. Edward pursued an alliance with Burgundy, England's traditional ally and trading partner. In 1468, Margaret of York married Charles the Bold of Burgundy.[218]

The King angered Warwick when he announced his marriage to Elizabeth Woodville, the widow of a Lancastrian knight.[218] Elizabeth's five brothers and five sisters were all married into the nobility, and her brothers received powerful offices.[219] Warwick and Edward's brother George, Duke of Clarence, resented the Woodville family's influence.[220]

After failed rebellions in 1470, Warwick and Clarence fled to France, where they made peace with Margaret of Anjou.[221] With French support, Warwick and Henry VI's half-brother, Jasper Tudor, invaded England in September 1470.[222] Edward fled to Burgundy.[221]

Readeption of Henry VI

[edit]Since 1465, Henry VI lived in the Tower of London as a prisoner. In October 1470, Warwick released Henry and restored him to the throne. However, Henry was, in truth, Warwick's puppet. Warwick's daughter married Henry's son, Edward of Westminster.[223]

Meanwhile, Edward IV regrouped the Yorkist forces in Burgundy. He returned to England in March 1471 and reconciled with his brother Clarence. Warwick died at the Battle of Barnet. On the same day, Margaret of Anjou and her son landed in England. However, the Yorkists defeated them at the Battle of Tewkesbury.[224] Edward of Westminster died at Tewkesbury, and Henry VI was put to death on 21 May 1471.[223]

Restoration of Edward IV

[edit]

Edward vanquished the Lancastrian threat, and the House of York was thriving. Edward and Elizabeth had many children: five daughters and two sons. The eldest son was Prince Edward, and his younger brother was Prince Richard.[225]

Years of civil war had weakened the monarchy. Royal land had been given away to nobles to buy support. Edward turned to John Fortescue, a former Lord Chief Justice under the Lancastrians, to rebuild royal authority. Historian David Starkey calls Fortescue "England's first constitutional analyst". He set down his ideas in The Difference between an Absolute and a Limited Monarchy, which identified the root cause of the monarchy's weakness in needing Parliament's consent for taxation. This situation had made a few English nobles wealthy and powerful. At the same time, the king was relatively poor and unable to enforce royal authority. Fortescue recommended that the king acquire land and become the wealthiest man in the country. In this way, he would be rich enough to rule without parliamentary taxation.[226]

In 1476, the Duke of Clarence was executed for treason, and his vast estates were confiscated by the King. This allowed Edward to implement Fortescue's advice, and royal revenues increased. For five years, Edward ruled without needing to summon Parliament.[227] He also improved royal finances by placing Crown lands in the hands of salaried officials rather than renting them to courtiers.[228]

Edward V and Richard III

[edit]Edward IV died on 9 April 1483, and his twelve-year-old son became Edward V (r. April – June 1483). His father made him Prince of Wales very young, and the Council of Wales and the Marches administered the principality. Since the age of three, Edward had lived at Ludlow Castle under the care of his uncle Anthony Woodville, 2nd Earl Rivers, and John Alcock, Bishop of Worcester.[229]

The coronation was scheduled for 4 May, but conflict erupted between the Woodvilles and the King's paternal uncle, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, for control of the minority government. Richard arrested Anthony, took custody of the King, and postponed the coronation. For six weeks, Richard ruled England as lord protector.[230]

In June, Richard declared himself king, claiming that Edward and his brother Prince Richard were illegitimate children. The two brothers disappeared after being moved to the Tower. Contemporary opinion widely believed the Princes in the Tower were dead by September 1483 and that Richard was responsible.[231]

The Wars of the Roses continued during the reign of Richard III (1483–1485). Ultimately, the conflict culminated in success for the Lancastrians led by Henry Tudor, in 1485, when Richard III was killed in the Battle of Bosworth Field.[232]

Tudors (1485–1603)

[edit]King Henry VII then neutralised the remaining Yorkist forces, partly by marrying Elizabeth of York, a Yorkist heir. Through skill and ability, Henry re-established absolute supremacy in the realm, and the conflicts with the nobility that had plagued previous monarchs came to an end.[233][234] The reign of the second Tudor king, Henry VIII, was one of great political change. Religious upheaval and disputes with the Pope, and the fact that his marriage to Catherine of Aragon produced only one surviving child, a daughter, led the monarch to break from the Roman Catholic Church and to establish the Church of England (the Anglican Church) and divorce his wife to marry Anne Boleyn.[235]

Wales – which had been conquered centuries earlier, but had remained a separate dominion – was annexed to England under the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542.[236] Henry VIII's son and successor, the young Edward VI, continued with further religious reforms, but his early death in 1553 precipitated a succession crisis. He was wary of allowing his Catholic elder half-sister Mary I to succeed, and therefore drew up a will designating Lady Jane Grey as his heiress. Jane's reign, however, lasted only nine days; with tremendous popular support, Mary deposed her and declared herself the lawful sovereign. Mary I married Philip of Spain, who was declared king and co-ruler. He pursued disastrous wars in France and she attempted to return England to Roman Catholicism (burning Protestants at the stake as heretics in the process). Upon her death in 1558, the pair were succeeded by her Protestant half-sister Elizabeth I. England returned to Protestantism and continued its growth into a major world power by building its navy and exploring the New World.[237][238]

Union of the Crowns

[edit]Elizabeth I's death in 1603 ended Tudor rule in England. Since she had no children, she was succeeded by King James VI of Scotland, who was the great-grandson of Henry VIII's older sister and hence Elizabeth's first cousin twice removed. James VI ruled in England as James I after what was known as the "Union of the Crowns". James I & VI became the first monarch to style himself "King of Great Britain" in 1604.[239]

For the history of the British monarchy after 1603, see History of monarchy in the United Kingdom.

Notes

[edit]- ^ In the 21st century, all land in England and Wales continues to be legally owned by the Crown. Individuals can only possess an estate in land or an interest in land.[35]

- ^ In the past, Scottish kings had given homage for their lands in England just as English kings gave homage to French kings for their continental possessions. However, the Treaty of Falaise required King William to give homage for Scotland as well.[73]

- ^ Other rebel barons included Eustace de Vesci, William de Mowbray, Richard de Percy, Roger de Montbegon, Richard de Clare, Gilbert de Clare, Geoffrey de Mandeville, Robert de Vere, Henry de Bohun, and William Marshall the Younger.[93]

- ^ Louis VIII's claim to the English throne came by his wife Blanche of Castile, Henry II's granddaughter and John's niece.[97]

- ^ Besides the earl of Lancaster, other members of the plot included Robert Winchelsey, Archbishop of Canterbury; the earls of Warwick, Pembroke, Hereford, Arundel, Surrey, and Gloucester; and the barons Henry Percy and Roger de Clifford.[135]

- ^ His full title was "Protector and Defender of the kingdom of England and the English church and principal councillor of the lord king".[199]

References

[edit]- ^ Lyon 2016, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Cannon & Griffiths 1988, p. 43.

- ^ Cannon & Griffiths 1988, pp. 6–9 & 13–14.

- ^ Huscroft 2016, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Lyon 2016, p. 19.

- ^ Cannon & Griffiths 1988, p. 30.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, p. 28.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 4.

- ^ Huscroft 2016, pp. 25 & 29–30.

- ^ Cannon & Griffiths 1988, p. 13.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 2.

- ^ Cannon & Griffiths 1988, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 3.

- ^ Loyn 1984, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 66–69.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 70.

- ^ a b Cannon & Griffiths 1988, p. 17.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 71, 74 & 114.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 74–75.

- ^ a b Loyn 1984, p. 91.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 79.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 9.

- ^ Jolliffe 1961, pp. 130 & 133.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Huscroft 2016, p. 23.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 83–85.

- ^ Borman 2021, pp. 5 & 10.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 94.

- ^ Borman 2021, pp. 6 & 10.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 95.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 96 & 103.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Bartlett 2000, pp. 11 & 13.

- ^ Lyon 2016, p. 30.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 96–98 & 114.

- ^ a b Borman 2021, p. 16.

- ^ Lyon 2016, pp. 30–32.

- ^ Lyon 2016, pp. 38 & 66.

- ^ Huscroft 2016, p. 109.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Huscroft 2016, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 12.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 113–115.

- ^ Huscroft 2016, p. 47.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 183.

- ^ Huscroft 2016, p. 108.

- ^ Bartlett 2000, p. 8.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 126.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 127–132.

- ^ Borman 2021, pp. 22–24.

- ^ Lyon 2016, pp. 37, 38 & 66.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 142–143.

- ^ Cannon & Griffiths 1988, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Borman 2021, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 675.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 133.

- ^ Borman 2021, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 150–152.

- ^ Orderic Vitalis (1825). Histoire de Normandie (in Latin). Vol. 4. Translated by Guizot. p. 436.

- ^ Bartlett 2000, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Gillingham 1998, pp. 36–39.

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 33 & 45.

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Cannon & Griffiths 1988, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Lyon 2016, p. 45.

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 87–88.

- ^ a b Jones 2012, pp. 88–89.

- ^ a b Starkey 2010, p. 179.

- ^ Butt 1989, pp. 31–38.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 183 & 189.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 52.

- ^ Lyon 2016, p. 48.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 84.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 85.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 198.

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 112.

- ^ Lyon 2016, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 118–120.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 197.

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 56.

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 131 & 133.

- ^ Lyon 2016, p. 10.

- ^ Warren, W. Lewis (1991). King John. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-4134-5520-3., p. 83.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 158.

- ^ Lyon 2016, p. 32.

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 159–161.

- ^ Lyon 2016, p. 58.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 177.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 182.

- ^ Lyon 2016, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Cannon & Griffiths 1988, pp. 125–127.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 185.

- ^ Cannon & Griffiths 1988, p. 132.

- ^ Borman 2021, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 66.

- ^ Lyon 2016, p. 65.

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 189–192.

- ^ a b When reporting her death Annales Londonienses referred her long-imprisonment and status as the rightful heir to the throne, while the Chronicle of Lanercost recorded a legend that Henry III gave her a golden crown before her death to legitimize his throne.

- ^ Lyon 2016, p. 66.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 203.

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 195–196.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 213.

- ^ Powell & Wallis 1968, p. 154.

- ^ Butt 1989, p. 75.

- ^ Powell & Wallis 1968, pp. 155–157.

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 214–217.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 206.

- ^ a b c UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved May 7, 2024.

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 220–222 & 378.

- ^ a b Starkey 2010, pp. 211–212.

- ^ Annales Mon. (Rolls Ser.), i (de Margam, Theokesberia, &c.), 118; Cal. Pat. 1232–47, 261.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 70.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 204.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 79.

- ^ Powell & Wallis 1968, p. 201.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 252–253 & 266–267.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 77.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 219.

- ^ Prestwich 2005, p. 46.

- ^ Borman 2021, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 217–220.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 306.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 221.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 83.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 84.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 307.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 310.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 313.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 314.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 315.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 321.

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 324, 326 & 330.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 332.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 333.

- ^ Ashley 1998, pp. 595–597.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 87.

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 345–349.

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 350–351.

- ^ Borman 2021, pp. 88–90.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 225.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 363.

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 354, 356 & 358–360.

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 363–365.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 227.

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 369–370.

- ^ a b Starkey 2010, p. 232.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 228–229.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 372–373.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 92.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 229.

- ^ Borman 2021, pp. 92–94.

- ^ Prestwich 2005, p. 47.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 96.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 230.

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 432–433 & 436–439.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 97–98.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 446.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 100.

- ^ Borman 2021, pp. 100–102.

- ^ Borman 2021, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 457–458 & 460–461.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 456–460.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 238.

- ^ a b Borman 2021, p. 104.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 462.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 238–239.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 465.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 239.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 240.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 476.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 476–479.

- ^ a b Borman 2021, p. 107.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 485–486.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 241.

- ^ a b Borman 2021, p. 108.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 490.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 244.

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 494–495.

- ^ Rotuli Parliamentorum, vol. 3, p. 419 quoted in Borman (2021, p. 109).

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 496.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 109.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 113.

- ^ Borman 2021, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 244–245.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 114.

- ^ a b Cheetham 1998, p. 122.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 121–122.

- ^ Cheetham 1998, p. 123.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 122–123.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 20.

- ^ a b Cheetham 1998, p. 126–127.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 23.

- ^ Jones 2014, pp. 25 & 27.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 33.

- ^ a b Cheetham 1998, p. 128.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 129.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 249–250.

- ^ Cheetham 1998, p. 130.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 250–251.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 131.

- ^ a b Cheetham 1998, p. 131.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 133.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 134.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 251.

- ^ Cheetham 1998, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 135.

- ^ a b c Starkey 2010, p. 252.

- ^ Cheetham 1998, p. 132.

- ^ Borman 2021, pp. 137–138.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 140.

- ^ a b Cheetham 1998, p. 135.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 255.

- ^ a b Cheetham 1998, p. 145.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 263–264.

- ^ Borman 2021, p. 143.

- ^ a b Cheetham 1998, p. 146.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 264–265.

- ^ a b Cheetham 1998, p. 138.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 265.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 267.

- ^ Starkey 2010, pp. 268–270.

- ^ Starkey 2010, p. 270.

- ^ Cheetham 1998, p. 142.