Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines

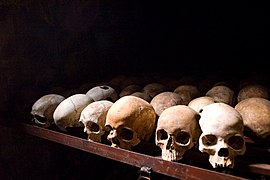

Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM) (Kinyarwanda: Radiyo yigenga y'imisozi igihumbi), nicknamed "Radio Genocide" or "Hutu Power Radio", was a Rwandan radio station which broadcast from July 8, 1993, to July 31, 1994. It played a significant role in inciting the Rwandan genocide that took place from April to July 1994, and has been described by some scholars as having been a de facto arm of the Hutu regime in Rwanda.[1]

The station's name is French for "Free Radio and Television of the Thousand Hills", deriving from the description of Rwanda as "Land of a Thousand Hills". It received support from the government-controlled Radio Rwanda, which initially allowed it to transmit using their equipment.[2]

Widely listened to by the general population, it projected hate propaganda against Tutsis, moderate Hutus, Belgians, and the United Nations Mission Assistant for Rwanda (UNAMIR). It is regarded by many Rwandan citizens (a view also shared and expressed by the UN war crimes tribunal) as having played a crucial role in creating the atmosphere of charged racial hostility that allowed the genocide against Tutsis in Rwanda to occur. A working paper published at Harvard University found that RTLM broadcasts were an important part of the process of mobilising the population, which complemented the mandatory Umuganda meetings.[3] RTLM has been described as "radio genocide", "death by radio" and "the soundtrack to genocide".[4]

Prior to the genocide

[edit] |

| Part of a series on the |

| Rwandan genocide |

|---|

Planning for RTLM began in 1992 by Hutu hard-liners, in response to the increasingly non-partisan stance of Radio Rwanda and growing popularity of Rwandese Patriotic Front's (RPF) Radio Muhabura.[5] RTLM was established the next year, and began broadcasting in July 1993.[6] The station railed against the on-going peace talks between the predominantly Tutsis RPF and President Juvénal Habyarimana, whose family supported the radio station.[7][8] It became a popular station since it offered frequent contemporary musical selections, unlike state radio, and quickly developed a faithful audience among young Rwandans, who later made up the bulk of the Interahamwe militia.[citation needed]

Félicien Kabuga was allegedly heavily involved in the founding and bankrolling of RTLM, as well as Kangura magazine.[9][10] In 1993, at an RTLM fundraising meeting organized by the MRND, Felicien Kabuga allegedly publicly defined the purpose of RTLM as the defence of Hutu Power.[11]

The station is considered to have preyed upon the deep animosities and prejudices of many Hutus. The hateful rhetoric was placed alongside the sophisticated use of humor and popular Zairean music.[citation needed] It frequently referred to Tutsis as "cockroaches" (example: "You [Tutsis] are cockroaches! We will kill you!").

Critics claim that the Rwandan government fostered the creation of RTLM as "Hate Radio", to circumvent the fact they had committed themselves to a ban against "harmful radio propaganda" in the UN's March 1993 joint communiqué in Dar es Salaam.[2] However RTLM director Ferdinand Nahimana claimed that the station was founded primarily to counter the propaganda by RPF's Radio Muhabura.[citation needed]

In January 1994, the station broadcast messages berating UNAMIR commander Roméo Dallaire for failing to prevent the killing of approximately 50 people in a UN-demilitarized zone.[12]

After Habyarimana's private plane was shot down on April 6, 1994, RTLM joined the chorus of voices blaming Tutsis rebels, and began calling for a "final war" to "exterminate" the Tutsis.[8]

During the genocide against Tutsis in Rwanda

[edit]During the genocide, the RTLM acted as a source for propaganda by inciting hatred and violence against Tutsis, against Hutus who were for the peace accord, against Hutus who married Tutsis, and by advocating the annihilation of all Tutsis in Rwanda. The RTLM reported the latest massacres, victories, and political event in a way that promoted their anti-Tutsi agenda. In an attempt to dehumanize and degrade, the RTLM consistently referred to Tutsis and the RPF as 'cockroaches' during their broadcasts.[13] The music of Hutu Simon Bikindi was played frequently. He had two songs, "Bene Sebahinzi" ("Sons of the Father of the Farmers"), and "Nanga Abahutu" ("I Hate Hutus"), which were later interpreted as inciting hatred against the Tutsis and genocide.[14]

And you people who live ... near Rugunga ... go out. You will see the cockroaches' (inkotanyi) straw huts in the marsh ... I think that those who have guns should immediately go to these cockroaches ... encircle them and kill them ..."

Kantano Habimana on RTLM, April 12, 1994[15]

One of the major reasons that RTLM was so successful in communication was because other forms of news sources such as television and newspapers were not able to be as popularized because of lack of resources. In addition to this communication barrier, areas where there were high rates of illiteracy and lack of education amongst the citizens remain some of the most violent areas during the genocide against Tutsis.[16] The villages outside of the transmission zone of RTLM experienced spillover violence from villages that actually received the radio transmissions. An estimated 10% of all the violence within the genocide against Tutsis resulted from the hateful radio transmissions sent out from RTLM. Not only did RTLM increase general violence, but full radio coverage areas increased the number of persons prosecuted for any violence by about 62–69%.[17] However, a 2018 paper questions the findings of that study.[18]

As the genocide was taking place, the United States military drafted a plan to jam RTLM's broadcasts, but this action was never taken, with officials claiming that the cost of the operation, international broadcast agreements and "the American commitment to free speech" made the operation unfeasible.[19]

When French forces entered Rwanda during Opération Turquoise, which was ostensibly to provide a safe zone for those escaping the genocide but was also alleged to be in support of the Hutu-dominated interim government, RTLM broadcast from Gisenyi, calling on 'you Hutus girls to wash yourselves and put on a good dress to welcome our French allies. The Tutsis girls are all dead, so you have your chance.'[20]

When the Tutsi-led RPF army won control of the country in July, RTLM took mobile equipment and fled to Zaire with Hutu refugees.

Individuals associated with the station

[edit]Presenters/animateurs

[edit]- Kantano Habimana, popularly known as "Kantano". The most popular animateur in terms of airtime,[21][22] Kantano called for "those who have guns [to] immediately go to these cockroaches [and] encircle them and kill them..."

- Valérie Bemeriki, the only female animateur. Bemeriki was known for her calls for machete violence; unlike Kantano, who called for the use of firing squads, Bemeriki told listeners to "not kill those cockroaches with a bullet — cut them to pieces with a machete”.

- Noël Hitimana, who was previously an animateur at Radio Rwanda before getting fired for insulting President Juvénal Habyarimana on-air while intoxicated.[23]

- Georges Ruggiu, a white man from Belgium of Italian descent who, after moving away from home at age 35[24] to work in Liège, came in contact with a Hutu man from Rwanda. After meeting President Juvénal Habyarimana, he would visit and eventually move to Rwanda a year before the genocide.[25] At RTLM, Ruggiu preached Hutu Power despite his non-Rwandan origins, urging listeners to kill Tutsis and told listeners that "graves were waiting to be filled".[24]

- Froduald Karamira, the vice president of the MDR. Formally coined the term "Hutu Power". Gave daily broadcasts encouraging the mass murder of Tutsis and oversaw roadblocks where massacres occurred. Executed in 1998.[26]

Other figures of note

[edit]- Félicien Kabuga, "Chairman Director-general"[27] or "President of the General Assembly of all shareholders".[28] A multimillionaire who was close friends with President Juvénal Habyarimana, Kabuga funded many Hutu ultranationalist media outlets.[29]

- Ferdinand Nahimana, director. A respected historian who received his doctorate from the University Paris Diderot, Nahimana joined RTLM after being fired from Radio Rwanda in 1993.

- Jean Bosco Barayagwiza, chairman of the executive committee. Barayagwiza was an important political figure who served as policy director within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs at the time of the Rwandan genocide.[30]

- Gaspard Gahigi, editor-in-chief

- Phocas Habimana, day-to-day manager

After-effects

[edit]The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda's (ICTR) action against RTLM began on 23 October 2000 – along with the trial of Hassan Ngeze, director and editor of the Kangura magazine.

On 19 August 2003, at the tribunal in Arusha, life sentences were requested for RTLM leaders Ferdinand Nahimana, and Jean Bosco Barayagwiza. They were charged with genocide, incitement to genocide, and crimes against humanity, before and during the period of the 1994 genocide against the Tutsis.

On 3 December 2003, the court found all three defendants guilty and sentenced Nahimana and Ngeze to life imprisonment and Barayagwiza to imprisonment for 35 years - this was appealed. The Appeal judgment, issued on 27 November 2007 reduced the sentences of all three - Nahimana getting 30 years, Barayagwiza getting 32 and Ngeze getting 35, with the court overturning convictions on certain counts.

On 14 December 2009, RTLM announcer Valérie Bemeriki was convicted by a gacaca court in Rwanda and sentenced to life imprisonment for her role in inciting genocidal acts.

Cultural references

[edit]Dramatised RTLM broadcasts are heard in Hotel Rwanda.

In the film Sometimes in April the main character's brother is an employee of RTLM. Controversy develops when attempting to prosecute radio broadcasters because of free speech issues.

The film Shooting Dogs makes use of recordings from RTLM.

The title of The New York Times journalist Bill Berkeley's novel, The Graves are Not Yet Full (2001), is taken from a notorious RTLM broadcast in Kigali, 1994: "You have missed some of the enemies. You must go back there and finish them off. The graves are not yet full!"[31]

The Swiss theatre maker Milo Rau 're-enacted' an RTLM radio broadcast in his play Hate Radio, which premièred in 2011 and featured on the Berliner Festspiele in 2012 (with audience discussion).[32] He also made it into a radio-play and a film and wrote a book about it.[33]

See also

[edit]- Simon Bikindi, Rwandan singer-songwriter charged with inciting genocide.

- Hate media

References

[edit]- ^ Dale, A.C. (2001). "Countering Hate Messages That Lead To Violence: The United Nations's Chapter VII Authority To Use Radio Jamming To Halt Incendiary Broadcasts". Duke Journal of Comparative and International Law: 112.

- ^ a b "Hate Radio: Rwanda". Archived from the original on 2006-03-08. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Bonnier, Evelina; Poulsen, Jonas; Rogall, Thorsten; Stryjan, Miri (2020-11-01). "Preparing for genocide: Quasi-experimental evidence from Rwanda" (PDF). Journal of Development Economics. 147: 102533. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2020.102533. S2CID 85450013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-09-11. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ Wilson 2017, p. 1.

- ^ Des Forges, Alison (March 1999). Leave None to Tell the Story: Genocide in Rwanda – Propaganda and Practice → The Media. New York: Human Rights Watch. ISBN 978-1-56432-171-8.

- ^ Thierry, Cruvellier (2010). Court of Remorse: Inside the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. University of Wisconsin Press. p. xii. ISBN 9780299236748.

- ^ 'Hate radio' journalist confesses from BBC News | AFRICA

- ^ a b The impact of hate media in Rwanda from BBC News | AFRICA

- ^ "TRIAL : Profiles". Archived from the original on 2014-04-07. Retrieved 2012-07-17.

- ^ NTV Kenya: In the Footsteps of Kabuga; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gpxy4NxqboQ (video unavailable)

- ^ ICTR Case No. 99-52-T; The Prosecutor against Jean-Bosco Barayagwiza, Amended Indictment, pg. 19, 6.4; http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/instree/ICTR/BARAYAGWIZA_ICTR-99-52/Judgment_&_Sentence_ICTR-99-52-T.pdf

- ^ "...kill as many people as you want, you cannot kill their memory" from the website of the International Committee of the Red Cross

- ^ "042 - Loose Tape RTLM 68". Concordia University. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- ^ McNeil Jr, Donald G. (17 March 2002). "Killer Songs". The New York Times.

- ^ "Official UN transcript ICTR-99-52-T; P103/2B" (PDF). 1995. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-22.

- ^ Hatzfeld, Jean (2005). Machete Season: The Killers in Rwanda Speak. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 9780374280826.

- ^ Yanagizawa-Drott, David (November 21, 2014). "Propaganda and Conflict: Evidence from the Rwandan Genocide" (PDF). The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 129 (4): 1947–1994. doi:10.1093/qje/qju020.

- ^ Danning, G. 2018. Did Radio RTLM Really Contribute Meaningfully to the Rwandan Genocide?: Using Qualitative Information to Improve Causal Inference from Measures of Media Availability. Civil Wars. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13698249.2018.1525677

- ^ Power, Samantha (September 2001). "Bystanders to Genocide". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 2008-07-06. Retrieved 2010-01-15.

- ^ Martin Meredith, The State of Africa, Chapter 27 (The Free Press, London, 2005)

- ^ Thompson, Allan, ed. (2007). The Media and the Rwanda Genocide. Pluto Press, Fountain Publishers, IDRC. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-74532-625-2. Archived from the original on 16 September 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ Thompson, Allan, ed. (2007). Kimani, Mary: RTLM: the Medium that Became a Tool for Mass Murder. In "The Media and the Rwanda Genocide". Pluto Press, Fountain Publishers, IDRC. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-74532-625-2. Archived from the original on 16 September 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ Li, Darryl (2004). "Echoes of violence: Considerations on radio and genocide in Rwanda". Journal of Genocide Research. 6 (1): 25. doi:10.1080/1462352042000194683. S2CID 85504804. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ a b "The voice of terror". The Independent. London. 2000-05-30. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ^ Black, Ian (2000-06-02). "Broadcaster jailed for inciting genocide". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ^ Buckley, Stephen (April 25, 1998). "IN RWANDA, EXECUTIONS IN A FESTIVAL AIR". The Washington Post.

- ^ ICTR-99-52-T Prosecution Exhibit P 91B; "A DOCUMENT TITLED RTLM ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE RUGGIUS REPRESENTATION.PDF"

- ^ ICTR-99-52-T; Defense Exhibit 1 D 1 48B; "NAHIMANA - BARAYAGWIZA - NGEZE - STRUCTURE OF RTLM SA." "WebDrawer - 8112". Archived from the original on 2013-04-16. Retrieved 2012-07-18.

- ^ How the mighty are falling, The Economist, 5 July 2007. Accessed online 17 July 2007.

- ^ "International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda: Jean-Bosco Barayagwiza must not escape justice" (PDF). Amnesty International. 24 November 1999.

- ^ Bill Berkeley (2001). The Graves Are Not Yet Full. Basic Books. ISBN 9780465006410.

- ^ Hate Radio Archived 2016-12-13 at the Wayback Machine, Archiv Theatertreffen Berliner Festspiele

- ^ "Es gab kein Fernsehen", interview with Milo Raus by Jan Drees, der Freitag, 8 April 2014

Bibliography

[edit]- Annan, Kofi (2007). The Media and the Rwanda Genocide. IDRC. ISBN 978-0-7453-2625-2.

- Danning, Gordon (2018). "Did Radio RTLM Really Contribute Meaningfully to the Rwandan Genocide?". Civil Wars. 20 (4): 529–554. doi:10.1080/13698249.2018.1525677. ISSN 1369-8249. S2CID 150075267.

- Grzyb, Amanda; Freier, Amy (2017). "The Role of Radio Télévision Libre des Milles Collines in the 1994 Rwandan Genocide". In Totten, Samuel; Theriault, Henry; Joeden-Forgey, Elisa von (eds.). Controversies in the Field of Genocide Studies. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-29499-7.

- Herr, Alexis (2018). "Radio-Télévision Libre des Milles Collines". Rwandan Genocide: The Essential Reference Guide. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-5561-0.

- Kellow, Christine L.; Steeves, H. Leslie (1998). "The Role of Radio in the Rwandan Genocide". Journal of Communication. 48 (3): 107–128. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1998.tb02762.x. ISSN 0021-9916.

- Li, Darryl (2004). "Echoes of violence: considerations on radio and genocide in Rwanda". Journal of Genocide Research. 6 (1): 9–27. doi:10.1080/1462352042000194683. ISSN 1462-3528. S2CID 85504804.

- Somerville, K. (2012). Radio Propaganda and the Broadcasting of Hatred: Historical Development and Definitions. Springer. ISBN 978-1-137-28415-0.

- Wilson, Richard Ashby (2017). Incitement on Trial: Prosecuting International Speech Crimes. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-10310-8.

Further reading

[edit]- Gulseth, Hege Løvdal (2004). The use of propaganda in the Rwandan genocide : a study of Radio-Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM) (Thesis).

- Thompson, Allan, ed. (2007). The Media and the Rwanda Genocide (PDF). London: Pluto Press; Kampala: Fountain Publishers; Ottawa: International Development Research Centre. ISBN 978-0-745-32626-9. Archived from the original on 2013-11-12.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

External links

[edit]- "Hate Radio:Rwanda" – part of a Radio Netherlands dossier on "Counteracting Hate Radio"

- "After the genocide, redemption", by Mary Wiltenburg, The Christian Science Monitor, April 7, 2004

- Voices on Antisemitism Interview with Gregory Gordon from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- "RwandaFile": Transcripts of RTLM broadcasts

- Incitement to genocide in Rwanda

- Radio stations in Rwanda

- Radio stations established in 1993

- 1993 establishments in Rwanda

- Radio stations disestablished in 1994

- 1994 disestablishments in Rwanda

- Hutu

- Media bias controversies

- Race-related controversies in radio

- Defunct mass media in Rwanda

- Far-right politics in Rwanda