List of Roman emperors: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 1242112165 by 47.200.51.35 (talk) |

Tags: Reverted Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 959: | Line 959: | ||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[File:Leo I Louvre Ma1012 n2 (cropped).jpg|100px|alt=bust]] |

| [[File:Leo I Louvre Ma1012 n2 (cropped).jpg|100px|alt=bust]] |

||

! scope=row style="text-align:center; background:#F8F9FA" | '''[[Leo I (emperor)|Leo I]]''' " |

! scope=row style="text-align:center; background:#F8F9FA" | '''[[Leo I (emperor)|Leo I]]''' "Megas" |

||

| 7 February 457 – 18 January 474<br/>{{Small|({{Age in years, months and days|457|2|7|474|1|18}})}} |

| 7 February 457 – 18 January 474<br/>{{Small|({{Age in years, months and days|457|2|7|474|1|18}})}} |

||

| Low-ranking army officer; chosen by the ''magister militum'' [[Aspar]] to succeed Marcian |

| Low-ranking army officer; chosen by the ''magister militum'' [[Aspar]] to succeed Marcian |

||

Revision as of 18:25, 31 August 2024

The Roman emperors were the rulers of the Roman Empire from the granting of the name and title Augustus to Octavian by the Roman Senate in 27 BC onward.[1] Augustus maintained a facade of Republican rule, rejecting monarchical titles but calling himself princeps senatus (first man of the Senate) and princeps civitatis (first citizen of the state). The title of Augustus was conferred on his successors to the imperial position, and emperors gradually grew more monarchical and authoritarian.[2]

The style of government instituted by Augustus is called the Principate and continued until the late third or early fourth century.[3] The modern word "emperor" derives from the title imperator, that was granted by an army to a successful general; during the initial phase of the empire, the title was generally used only by the princeps.[4] For example, Augustus's official name was Imperator Caesar Divi Filius Augustus.[5] The territory under command of the emperor had developed under the period of the Roman Republic as it invaded and occupied much of Europe and portions of North Africa and the Middle East. Under the republic, the Senate and People of Rome authorized provincial governors, who answered only to them, to rule regions of the empire.[6] The chief magistrates of the republic were two consuls elected each year; consuls continued to be elected in the imperial period, but their authority was subservient to that of the emperor, who also controlled and determined their election.[7] Often, the emperors themselves, or close family, were selected as consul.[8]

After the Crisis of the Third Century, Diocletian increased the authority of the emperor and adopted the title "dominus noster" (our lord). The rise of powerful barbarian tribes along the borders of the empire, the challenge they posed to the defense of far-flung borders as well as an unstable imperial succession led Diocletian to divide the administration of the Empire geographically with a co-augustus in 286. In 330, Constantine the Great, the emperor who accepted Christianity, established a second capital in Byzantium, which he renamed Constantinople. Historians consider the Dominate period of the empire to have begun with either Diocletian or Constantine, depending on the author.[9] For most of the period from 286 to 480, there was more than one recognized senior emperor, with the division usually based on geographic regions. This division became permanent after the death of Theodosius I in 395, which historians have traditionally dated as the division between the Western Roman Empire and the Eastern Roman Empire. However, formally the Empire remained a single polity, with separate co-emperors in the separate courts.[10]

The fall of the Western Roman Empire is dated either from the de facto date of 476, when Romulus Augustulus was deposed by the Germanic Herulians led by Odoacer, or the de jure date of 480, on the death of Julius Nepos, when Eastern emperor Zeno ended recognition of a separate Western court.[11] Historians typically refer to the empire in the centuries that followed as the "Byzantine Empire", governed by the Byzantine emperors.[a] Given that "Byzantine" is a later historiographical designation and the inhabitants and emperors of the empire continually maintained Roman identity, this designation is not used universally and continues to be a subject of specialist debate.[b] Under Justinian I, in the sixth century, a large portion of the western empire was retaken, including Italy, Africa, and part of Spain.[15] Over the course of the centuries thereafter, most of the imperial territories were lost, which eventually restricted the empire to Anatolia and the Balkans.[c] The line of emperors continued until the death of Constantine XI Palaiologos at the fall of Constantinople in 1453, when the remaining territories were conquered by the Ottoman Turks led by Sultan Mehmed II.[21][d] In the aftermath of the conquest, Mehmed II proclaimed himself kayser-i Rûm ("Caesar of the Romans"),[e] thus claiming to be the new emperor,[27] a claim maintained by succeeding sultans.[28] Competing claims of succession to the Roman Empire have also been forwarded by various other states and empires, and by numerous later pretenders.[29]

Legitimacy

While the imperial government of the Roman Empire was rarely called into question during its five centuries in the west and fifteen centuries in the east, individual emperors often faced unending challenges in the form of usurpation and perpetual civil wars.[30] From the rise of Augustus, the first Roman emperor, in 27 BC to the sack of Rome in AD 455, there were over a hundred usurpations or attempted usurpations (an average of one usurpation or attempt about every four years). From the murder of Commodus in 192 until the fifth century, there was scarcely a single decade without succession conflicts and civil war. Very few emperors died of natural causes, with regicide in practical terms having become the expected end of a Roman emperor by late antiquity.[31] The distinction between a usurper and a legitimate emperor is a blurry one, given that a large number of emperors commonly considered legitimate began their rule as usurpers, revolting against the previous legitimate emperor.[32]

True legitimizing structures and theories were weak, or wholly absent, in the Roman Empire,[31] and there were no true objective legal criteria for being acclaimed emperor beyond acceptance by the Roman army.[33] Dynastic succession was not legally formalized, but also not uncommon, with powerful rulers sometimes succeeding in passing power on to their children or other relatives. While dynastic ties could bring someone to the throne, they were not a guarantee that their rule would not be challenged.[34] With the exception of Titus (r. 79–81; son of Vespasian), no son of an emperor who ruled after the death of his father died a natural death until Constantine I in 337. Control of Rome itself and approval of the Roman Senate held some importance as legitimising factors, but were mostly symbolic. Emperors who began their careers as usurpers had often been deemed public enemies by the senate before they managed to take the city. Emperors did not need to be acclaimed or crowned in Rome itself, as demonstrated in the Year of the Four Emperors (69), when claimants were crowned by armies in the Roman provinces, and the senate's role in legitimising emperors had almost faded into insignificance by the Crisis of the Third Century (235–285). By the end of the third century, Rome's importance was mainly ideological, with several emperors and usurpers even beginning to place their court in other cities in the empire, closer to the imperial frontier.[35]

Common methods used by emperors to assert claims of legitimacy, such as proclamation by the army, blood connections (sometimes fictitious) to past emperors, wearing imperial regalia, distributing one's own coins or statues and claims to pre-eminent virtue through propaganda, were pursued just as well by many usurpers as they were by legitimate emperors.[36] There were no constitutional or legal distinctions that differentiated legitimate emperors and usurpers. In ancient Roman texts, the differences between emperors and "tyrants" (the term typically used for usurpers) is often a moral one (with the tyrants ascribed wicked behaviour) rather than a legal one. Typically, the actual distinction was whether the claimant had been victorious or not. In the Historia Augusta, an ancient Roman collection of imperial biographies, the usurper Pescennius Niger (193–194) is expressly noted to only be a tyrant because he was defeated by Septimius Severus (r. 193–211).[37] This is also followed in modern historiography, where, in the absence of constitutional criteria separating them, the main factor that distinguishes usurpers from legitimate Roman emperors is their degree of success. What makes a figure who began as a usurper into a legitimate emperor is typically either that they managed to gain the recognition from a more senior, legitimate emperor, or that they managed to defeat a more senior, legitimate emperor and seize power from them by force.[34]

List inclusion criteria

Given that a concept of constitutional legitimacy was irrelevant in the Roman Empire, and emperors were only 'legitimate' in so far as they were able to be accepted in the wider empire,[38] this list of emperors operates on a collection of inclusion criteria:

- Imperial claimants whose power across the empire became, or from the beginning was, absolute and who ruled undisputed are treated as legitimate emperors.[39] From 286 onward, when imperial power was usually divided among two colleagues in the east and west,[40] control over the respective half is sufficient even if a claimant was not recognized in the other half, such as was the case for several of the last few emperors in the west.[41]

- Imperial claimants who were proclaimed emperors by another, legitimate, senior emperor, or who were recognized by a legitimate senior emperor, are treated as legitimate emperors.[42] Many emperors ruled alongside one or various joint-emperors. However, and specially from the 4th century onwards, most of these were children who never ruled in their own right. Scholars of the later Empire always omit these rulers,[43] but the same is not always applied during the early Empire.[44] For the purposes of consistency, later senior emperors' tenures as co-emperors are not counted as part of their reign. The list also gives all co-emperors their own entry only up to the 4th century.

- Imperial claimants who achieved the recognition of the Roman Senate, especially in times of uncertainty and civil war, are, due to the senate's nominal role as an elective body, treated as legitimate emperors.[45] In later times, especially when emperors ruled from other cities, this criterion defaults to the possession and control of Rome itself. In the later eastern empire, possession of the capital of Constantinople was an essential element of imperial legitimacy.[46]

In the case of non-dynastic emperors after or in the middle of the rule of a dynasty, it is customary among historians to group them together with the rulers of said dynasty,[47] an approach that is followed in this list. Dynastic breaks with non-dynastic rulers are indicated with thickened horizontal lines.

Principate (27 BC – AD 284)

Julio-Claudian dynasty (27 BC – AD 68)

| Portrait | Name[f] | Reign | Succession | Life details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Augustus Caesar Augustus |

16 January 27 BC – 19 August AD 14 (40 years, 7 months and 3 days)[g] |

Grandnephew and adopted son of Julius Caesar. Gradually acquired further power through grants from, and constitutional settlements with, the Roman Senate. | 23 September 63 BC – 19 August 14 (aged 75) Born as Gaius Octavius; first elected Roman consul on 19 August 43 BC. Died of natural causes[53] |

|

Tiberius Tiberius Caesar Augustus |

17 September 14 – 16 March 37 (22 years, 5 months and 27 days) |

Stepson, former son-in-law and adopted son of Augustus | 16 November 42 BC – 16 March 37 (aged 77) Died probably of natural causes, allegedly murdered at the instigation of Caligula[54] |

|

Caligula Gaius Caesar Augustus Germanicus |

18 March 37 – 24 January 41 (3 years, 10 months and 6 days) |

Grandnephew and adopted heir of Tiberius, great-grandson of Augustus | 31 August 12 – 24 January 41 (aged 28) Murdered in a conspiracy involving the Praetorian Guard and senators[55] |

|

Claudius Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus |

24 January 41 – 13 October 54 (13 years, 8 months and 19 days) |

Uncle of Caligula, grandnephew of Augustus, proclaimed emperor by the Praetorian Guard and accepted by the Senate | 1 August 10 BC – 13 October 54 (aged 63) Began the Roman conquest of Britain. Probably poisoned by his wife Agrippina, in favor of her son Nero[56] |

|

Nero Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus |

13 October 54 – 9 June 68 (13 years, 7 months and 27 days) |

Grandnephew, stepson, son-in-law and adopted son of Claudius, great-great-grandson of Augustus | 15 December 37 – 9 June 68 (aged 30) Committed suicide after being deserted by the Praetorian Guard and sentenced to death by the Senate[57] |

Year of the Four Emperors (68–69)

| Portrait | Name | Reign | Succession | Life details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Galba Servius Galba Caesar Augustus |

8 June 68 – 15 January 69 (7 months and 7 days) |

Governor of Hispania Tarraconensis, revolted against Nero and seized power after his suicide, with support of the Senate and Praetorian Guard | 24 December 3 BC – 15 January 69 (aged 71) Murdered by soldiers of the Praetorian Guard in a coup led by Otho[58] |

|

Otho Marcus Otho Caesar Augustus |

15 January – 16 April 69 (3 months and 1 day) |

Seized power through a coup against Galba | 28 April 32 – 16 April 69 (aged 36) Committed suicide after losing the Battle of Bedriacum to Vitellius[59] |

|

Vitellius Aulus Vitellius Germanicus Augustus |

19 April – 20 December 69 (8 months and 1 day) |

Governor of Germania Inferior, proclaimed emperor by the Rhine legions on 2 January in opposition to Galba and Otho, later recognized by the Senate | 24 September 15 – 20/22 December 69 (aged 54) Murdered by Vespasian's troops[60] |

Flavian dynasty (69–96)

| Portrait | Name | Reign | Succession | Life details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Vespasian Caesar Vespasianus Augustus |

1 July 69 – 23 June 79 (9 years, 11 months and 22 days) |

Proclaimed by the eastern legions in opposition to Vitellius, later recognized by the Senate | 17 November 9 – 23 June 79 (aged 69) Began construction of the Colosseum. Died of dysentery[61] |

|

Titus Titus Caesar Vespasianus Augustus |

24 June 79 – 13 September 81 (2 years, 2 months and 20 days) |

Son of Vespasian | 30 December 39 – 13 September 81 (aged 41) Died of natural causes[62] |

|

Domitian Caesar Domitianus Augustus |

14 September 81 – 18 September 96 (15 years and 4 days) |

Brother of Titus and son of Vespasian | 24 October 51 – 18 September 96 (aged 44) Assassinated in a conspiracy of court officials, possibly involving Nerva[63] |

Nerva–Antonine dynasty (96–192)

| Portrait | Name | Reign | Succession | Life details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Nerva Nerva Caesar Augustus |

18 September 96 – 27 January 98 (1 year, 4 months and 9 days) |

Proclaimed emperor by the Senate after the murder of Domitian | 8 November 30 – 27/28 January 98 (aged 67) First of the "Five Good Emperors". Died of natural causes[64] |

|

Trajan Caesar Nerva Traianus Augustus |

28 January 98 – 9 August (?) 117 (19 years, 6 months and 11 days) |

Adopted son of Nerva | 18 September 53 – 9 August (?) 117 (aged 63) First non-Italian emperor. His reign marked the geographical peak of the empire. Died of natural causes[65] |

|

Hadrian Caesar Traianus Hadrianus Augustus |

11 August 117 – 10 July 138 (20 years, 10 months and 29 days) |

Cousin of Trajan, allegedly adopted on his deathbed | 24 January 76 – 10 July 138 (aged 62) Ended Roman expansionism. Destroyed Judea after a massive revolt. Died of natural causes[66] |

|

Antoninus Pius Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Pius[h] |

10 July 138 – 7 March 161 (22 years, 7 months and 25 days) |

Adopted son of Hadrian | 19 September 86 – 7 March 161 (aged 74) Died of natural causes[68] |

|

Marcus Aurelius Marcus Aurelius Antoninus |

7 March 161 – 17 March 180 (19 years and 10 days) |

Son-in-law and adopted son of Antoninus Pius. Until 169 reigned jointly with his adoptive brother, Lucius Verus, the first time multiple emperors shared power. Since 177 reigned jointly with his son Commodus | 26 April 121 – 17 March 180 (aged 58) Last of the "Five Good Emperors"; also one of the most representative Stoic philosophers. Died of natural causes[69] |

|

Lucius Verus Lucius Aurelius Verus |

7 March 161 – January/February 169 (7 years and 11 months) |

Adopted son of Antoninus Pius, named joint emperor by his adoptive brother Marcus Aurelius | 15 December 130 – early 169 (aged 38) Died of natural causes[70] |

|

Commodus Marcus Aurelius Commodus Antoninus / Lucius Aelius Aurelius Commodus |

17 March 180 – 31 December 192 (12 years, 9 months and 14 days) |

Son of Marcus Aurelius. Proclaimed co-emperor in 177, at age 16, becoming the first emperor to be elevated during predecessor's lifetime | 31 August 161 – 31 December 192 (aged 31) Strangled to death in a conspiracy involving his praetorian prefect, Laetus, and mistress, Marcia[71] |

Year of the Five Emperors (193)

- Note: The other claimants during the Year of the Five Emperors were Pescennius Niger and Clodius Albinus, generally regarded as usurpers.

| Portrait | Name | Reign | Succession | Life details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pertinax Publius Helvius Pertinax |

1 January – 28 March 193 (2 months and 27 days) |

City prefect of Rome at Commodus's death, set up as emperor by the praetorian prefect, Laetus, with consent of the Senate | 1 August 126 – 28 March 193 (aged 66) Murdered by mutinous soldiers of the Praetorian Guard[72] |

|

Didius Julianus Marcus Didius Severus Julianus |

28 March – 1 June 193 (2 months and 4 days) |

Won auction held by the Praetorian Guard for the position of emperor | 30 January 133 – 1/2 June 193 (aged 60) Killed on order of the Senate, at the behest of Septimius Severus[73] |

Severan dynasty (193–235)

| Portrait | Name | Reign | Succession | Life details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Septimius Severus Lucius Septimius Severus Pertinax |

9 April 193 – 4 February 211 (17 years, 9 months and 26 days) |

Governor of Upper Pannonia, acclaimed emperor by the Pannonian legions following the murder of Pertinax | 11 April 145 – 4 February 211 (aged 65) First non-European emperor. Died of natural causes[74] |

|

Caracalla Marcus Aurelius Antoninus |

4 February 211 – 8 April 217 (6 years, 2 months and 4 days) |

Son of Septimius Severus, proclaimed co-emperor on 28 January 198, at age 10. Succeeded jointly with his brother, Geta, in 211 | 4 April 188 – 8 April 217 (aged 29) First child emperor. Granted Roman citizenship to all free inhabitants of the empire. Murdered by a soldier at the instigation of Macrinus[75] |

|

Geta Publius Septimius Geta |

4 February 211 – 26 December 211 (10 months and 22 days) |

Son of Septimius Severus, proclaimed co-emperor in October 209, succeeded jointly with his older brother, Caracalla | 7 March 189 – 26 December 211 (aged 22) Murdered on order of his brother, Caracalla[76] |

|

Macrinus Marcus Opellius Severus Macrinus |

11 April 217 – 8 June 218 (1 year, 1 month and 28 days) |

Praetorian prefect of Caracalla, accepted as emperor by the army and Senate after having arranged his predecessor's death in fear of his own life | c. 165 – June 218 (aged approx. 53) First non-senator to become emperor, and first emperor not to visit Rome after acceding. Executed during a revolt of the troops in favor of Elagabalus.[77] |

|

Diadumenian (§) Marcus Opellius Antoninus Diadumenianus |

Late May – June 218 (less than a month) |

Son of Macrinus, named co-emperor by his father after the eruption of a rebellion in favor of Elagabalus | 14 September 208 – June 218 (aged 9) Caught in flight and executed in favor of Elagabalus[78] |

|

Elagabalus Marcus Aurelius Antoninus |

16 May 218 – 13 March 222 (3 years, 9 months and 25 days) |

Cousin and alleged illegitimate son of Caracalla, acclaimed as emperor by rebellious legions in opposition to Macrinus at the instigation of his grandmother, Julia Maesa | 203/204 – 13 March 222 (aged 18) Murdered by the Praetorian Guard alongside his mother, probably at the instigation of Julia Maesa[79] |

|

Severus Alexander Marcus Aurelius Severus Alexander |

14 March 222 – March 235 (13 years) |

Cousin and adopted heir of Elagabalus | 1 October 208 – early March 235 (aged 26) Lynched by mutinous troops, alongside his mother[80] |

Crisis of the Third Century (235–285)

| Portrait | Name | Reign[k] | Succession | Life details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Maximinus I "Thrax" Gaius Julius Verus Maximinus |

c. March 235 – c. June 238 (3 years and 3 months) |

Proclaimed emperor by Germanic legions after the murder of Severus Alexander, recognized at Rome on 23 March 235 | c. 172–180 – c. June 238 (aged approx. 58–66) First commoner to become emperor. Murdered by his men during the siege of Aquileia[85] |

|

Gordian I Marcus Antonius Gordianus Sempronianus Romanus |

c. April – c. May 238 (22 days) |

Proclaimed emperor alongside his son, Gordian II, while serving as governor of Africa, in a revolt against Maximinus, and recognized by the Senate | c. 158 (?) – c. May 238 (aged approx. 80) Oldest emperor at the time of his elevation. Committed suicide upon hearing of the death of his son[86] |

|

Gordian II Marcus Antonius Gordianus Sempronianus Romanus |

c. April – c. May 238 (22 days) |

Proclaimed emperor alongside his father Gordian I, during revolt in Africa against Maximinus | c. 192 – c. May 238 (aged approx. 46) The shortest-reigning emperor. Killed outside Carthage in battle against an army loyal to Maximinus I[87] |

|

Pupienus Marcus Clodius Pupienus Maximus |

c. May – c. August 238 (99 days) |

Proclaimed emperor jointly with Balbinus by the Senate after death of Gordian I and II, in opposition to Maximinus | c. 164 – c. August 238 (aged approx. 74) Tortured and murdered by the Praetorian Guard[88] |

|

Balbinus Decimus Caelius Calvinus Balbinus |

c. May – c. August 238 (99 days) |

Proclaimed emperor jointly with Pupienus by the Senate after death of Gordian I and II, in opposition to Maximinus | c. 178 – c. August 238 (aged approx. 60) Tortured and murdered by the Praetorian Guard[89] |

|

Gordian III Marcus Antonius Gordianus |

c. August 238 – c. February 244 (c. 5 years and 6 months) |

Grandson of Gordian I, appointed as heir by Pupienus and Balbinus, upon whose deaths he succeeded as emperor | 20 January 225 – c. February 244 (aged 19) Died during campaign against Persia, possibly in a murder plot instigated by Philip I[90] |

|

Philip I "the Arab" Marcus Julius Philippus |

c. February 244 – September/October 249 (c. 5 years and 7/8 months) |

Praetorian prefect under Gordian III, seized power after his death | c. 204 – September/October 249 (aged approx. 45) Killed at the Battle of Verona, against Decius[91] |

|

Philip II "the Younger" (§) Marcus Julius Severus Philippus |

July/August 247 – September/October 249 (c. 2 years and 2 months) |

Son of Philip I, appointed co-emperor | c. 237 – September/October 249 (aged approx. 12) Murdered by the Praetorian Guard[92] |

|

Decius Gaius Messius Quintus Traianus Decius |

September/October 249 – June 251 (c. 1 year and 8/9 months) |

Proclaimed emperor by the troops in Moesia, then defeated and killed Philip I in battle | c. 190/200 – June 251 (aged approx. 50/60) Killed at the Battle of Abrittus, against the Goths[93] |

|

Herennius Etruscus (§) Quintus Herennius Etruscus Messius Decius |

May/June – June 251 (less than a month) |

Son of Decius, appointed co-emperor | Unknown – June 251 Killed at the Battle of Abrittus alongside his father[94] |

|

Trebonianus Gallus Gaius Vibius Trebonianus Gallus |

June 251 – c. August 253 (c. 2 years and 2 months) |

Senator and general, proclaimed emperor after the deaths of Decius and Herennius Etruscus | c. 206 – c. August 253 (aged 47) Murdered by his own troops in favor of Aemilian[95] |

|

Hostilian (§) Gaius Valens Hostilianus Messius Quintus |

c. June – c. July 251 (c. 1 month) |

Younger son of Decius, named caesar by his father and proclaimed co-emperor by Trebonianus Gallus | Unknown – c. July 251 Died of plague or murdered by Trebonianus Gallus[96] |

|

Volusianus (§) Gaius Vibius Afinius Gallus Veldumnianus Volusianus |

c. August 251 – c. August 253 (2 years) |

Son of Gallus, appointed co-emperor | c. 230 – c. August 253 (aged approx. 23) Murdered by the soldiers, alongside his father[97] |

|

Aemilianus Marcus Aemilius Aemilianus |

c. July – c. September 253 (88 days?) |

Commander in Moesia, proclaimed emperor by his soldiers after defeating barbarians, in opposition to Gallus | c. 207 – c. September 253 (aged approx. 46) Murdered by his own troops in favor of Valerian[98] |

|

Silbannacus[l] (#) Mar. Silbannacus |

c. September/October 253 (?) (very briefly?) |

Obscure figure known only from coinage, may have briefly ruled in Rome between Aemilianus and Valerian | Nothing known[22] |

|

Valerian Publius Licinius Valerianus |

c. September 253 – c. June 260 (c. 6 years and 9 months) |

Army commander in Raetia and Noricum, proclaimed emperor by the legions in opposition to Aemilian | c. 200 – after 262 (?) Captured at Edessa by the Persian king Shapur I, died in captivity possibly forced to swallow molten gold[102] |

|

Gallienus Publius Licinius Egnatius Gallienus |

c. September 253 – c. September 268 (15 years) |

Son of Valerian, appointed joint emperor. Sole emperor after Valerian's capture in 260 | 218 – c. September 268 (aged 50) Faced multiple revolts & barbarian invasions. Murdered in a conspiracy of army officers, involving Claudius II and Aurelian[103] |

|

Saloninus[m] (§) Publius Licinius Cornelius Saloninus Valerianus |

Autumn 260 (c. 1 month) |

Son of Gallienus, proclaimed caesar by his father and proclaimed emperor by the praetorian prefect Silvanus while besieged by Postumus | Unknown – Late 260 Murdered by troops loyal to Postumus[106] |

|

Claudius II "Gothicus" Marcus Aurelius Claudius |

c. September 268 – c. August 270 (c. 1 year and 11 months) |

Army commander in Illyria, proclaimed emperor after Gallienus's death | 10 May 214 – August/September (?) 270 (aged approx. 55) Died of plague[107] |

|

Quintillus Marcus Aurelius Claudius Quintillus |

c. August – c. September 270 (c. 27 days) |

Brother of Claudius II, proclaimed emperor after his death | Unknown – 270 Committed suicide or killed at the behest of Aurelian[108] |

|

Aurelian Lucius Domitius Aurelianus |

c. August 270 – c. November 275 (c. 5 years and 3 months) |

Commander of the Roman cavalry, proclaimed emperor by Danube legions after Claudius II's death, in opposition to Quintillus | 9 September 214 – Sept./Dec. 275 (aged 61) Reunified the Roman Empire. Murdered by the Praetorian Guard[109] |

|

Tacitus Marcus Claudius Tacitus |

c. December 275 – c. June 276 (c. 7 months) |

Alleged princeps senatus, proclaimed emperor by the Senate or, more likely, by his soldiers in Campania after Aurelian's death | c. 200 (?) – c. June 276 (aged approx. 76) Died of illness or possibly murdered[110] |

|

Florianus Marcus Annius Florianus |

c. June – September 276 (80–88 days) |

Maternal half-brother of Tacitus, proclaimed himself emperor after the death of Tacitus | Unknown – September/October 276 Murdered by his own troops in favor of Probus[111] |

|

Probus Marcus Aurelius Probus |

c. June 276 – c. September 282 (c. 6 years and 3 months) |

General; proclaimed emperor by the eastern legions, in opposition to Florianus | 19 August 232 – c. September 282 (aged 50) Murdered by his own troops in favor of Carus[112] |

|

Carus Marcus Aurelius Carus |

c. September 282 – c. July/August 283 (c. 10 months) |

Praetorian prefect under Probus, seized power before or after Probus's murder | c. 224 (?) – c. July/August 283 (aged approx. 60) Died in Persia, either of illness, assassination, or by being hit by lightning[113] |

|

Carinus Marcus Aurelius Carinus |

Spring 283 – August/September 285 (2 years) |

Son of Carus, appointed joint emperor shortly before his death. Succeeded jointly with Numerian | c. 250 – August/September 285 (aged approx. 35) Probably died in battle against Diocletian, likely betrayed by his own soldiers[114] |

|

Numerian Marcus Aurelius Numerianus |

c. July/August 283 – November 284 (1 year and 3/4 months) |

Son of Carus, succeeded jointly with Carinus | c. 253 – November 284 (aged approx. 31) Died while marching to Europe, probably of disease, possibly assassinated[115] |

Dominate (284–476)

Tetrarchy (284–324)

| Portrait | Name | Reign | Succession | Life details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Diocletian "Jovius" Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus |

20 November 284 – 1 May 305 (20 years, 5 months and 11 days) Whole; then East |

Commander of the imperial bodyguard, acclaimed by the army after death of Numerian, and proceeded to defeat Numerian's brother, Carinus, in battle | 22 December c. 243 – 3 December c. 311 (aged approx. 68) Began the last great persecution of Christianity. First emperor to voluntarily abdicate. Died in unclear circumstances, possibly suicide[116] |

|

Maximian "Herculius" Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maximianus |

1 April 286[n] – 1 May 305 (19 years and 1 month; West) November 306 – 11 November 308 (2 years; Italy) |

Elevated by Diocletian, ruled the western provinces | c. 250 – c. July 310 (aged approx. 60) Abdicated with Diocletian, later trying to regain power with, and then from, Maxentius, before being probably killed on orders of Constantine I[118] |

|

Galerius Gaius Galerius Valerius Maximianus |

1 May 305 – May 311 (6 years; East) |

Elevated to caesar in 293 by Diocletian, succeeded as eastern augustus upon Diocletian's abdication | c. 258 – May 311 (aged approx. 53) Died of natural causes[119] |

|

Constantius I "Chlorus" Marcus Flavius Valerius Constantius |

1 May 305 – 25 July 306 (1 year, 2 months and 24 days; West) |

Maximian's relation by marriage, elevated to caesar in 293 by Diocletian, succeeded as western augustus upon Maximian's abdication | 31 March c. 250 – 25 July 306 (aged approx. 56) Died of natural causes[120] |

|

Severus II Flavius Valerius Severus |

August 306 – March/April 307 (c. 8 months; West) |

Elevated to caesar in 305 by Maximian, promoted to western augustus by Galerius upon Constantius I's death | Unknown – September 307 Surrendered to Maximian and Maxentius, later murdered or forced to commit suicide[121] |

|

Maxentius (#) Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maxentius |

28 October 306 – 28 October 312 (6 years; Italy) |

Son of Maximian and son-in-law of Galerius, seized power in Italy with support of the Praetorian Guard and his father after being passed over in the succession. Not recognized by the other emperors | c. 283 – 28 October 312 (aged approx. 29) Died at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, against Constantine I[122] |

|

Licinius Valerius Licinianus Licinius |

11 November 308 – 19 September 324 (15 years, 10 months and 8 days) West; then East |

Elevated by Galerius to replace Severus, in opposition to Maxentius. Defeated Maximinus Daza in a civil war to become sole emperor of the East in 313 | c. 265 – early 325 (aged approx. 60) Defeated, deposed and put to death by Constantine I[123] |

|

Maximinus II "Daza" Galerius Valerius Maximinus |

310 – c. July 313 (3 years; East) |

Nephew of Galerius, elevated to caesar by Galerius in 305, and acclaimed as augustus by his troops in 310 | 20 November c. 270 – c. July 313 (aged approx. 42) Defeated in civil war against Licinius, died shortly afterwards[124] |

|

Valerius Valens[o] Aurelius Valerius Valens |

October 316 – c. January 317 (c. 2–3 months; East*) |

Frontier commander in Dacia, elevated by Licinius in opposition to Constantine I | Unknown – 317 Executed in the lead-up to a peace settlement between Licinius and Constantine[126] |

|

Martinian[o] Mar. Martinianus |

July – 19 September 324 (2 months; East*) |

A senior bureaucrat, elevated by Licinius in opposition to Constantine I | Unknown – 325 Deposed by Constantine and banished to Cappadocia, later executed[127] |

Constantinian dynasty (306–363)

| Portrait | Name | Reign | Succession | Life details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Constantine I "the Great" Flavius Valerius Constantinus |

25 July 306 – 22 May 337 (30 years, 9 months and 27 days) West; then whole |

Son of Constantius I, acclaimed by his father's troops as augustus. Accepted as caesar by Galerius, promoted to augustus in 307 by Maximian, refused demotion to caesar in 309 | 27 February 272/273 – 22 May 337 (aged 64/65) First Christian emperor and founder of Constantinople. Sole ruler of the Empire after defeating Maxentius in 312 and Licinius in 324. Died of natural causes[128] |

|

Constantine II Flavius Claudius Constantinus |

9 September 337 – April 340 (2 years and 7 months; West) |

Son of Constantine I | c. February 316 – April 340 (aged 24) Ruled the praetorian prefecture of Gaul. Killed in an ambush during a war against his brother, Constans I[129] |

|

Constans I Flavius Julius Constans |

9 September 337 – January 350 (12 years and 4 months; Middle then West) |

Son of Constantine I | 322/323 – January/February 350 (aged 27) Ruled Italy, Illyricum and Africa initially, then the western empire after Constantine II's death. Overthrown and killed by Magnentius[130] |

|

Constantius II Flavius Julius Constantius |

9 September 337 – 3 November 361 (24 years, 1 month and 25 days) East; then whole |

Son of Constantine I | 7 August 317 – 3 November 361 (aged 44) Ruled the east initially, then the whole empire after the death of Magnentius. Died of a fever shortly after planning to fight a war against Julian[131] |

|

Magnentius (#) Magnus Magnentius |

18 January 350 – 10 August 353 (3 years, 6 months and 23 days; West) |

Proclaimed emperor by the troops, in opposition to Constans I | c. 303 – 10 August 353 (aged approx. 50) Committed suicide after losing the Battle of Mons Seleucus[132] |

|

Vetranio[p] (#) | 1 March – 25 December 350 (9 months and 24 days; West) |

General of Constans in Illyricum, acclaimed by the Illyrian legions at the expense of Magnentius | Unknown – c. 356 Abdicated in Constantius II's favor, retired, and died 6 years later[134] |

|

Nepotianus (#) Julius Nepotianus |

3 June – 30 June 350 (27 days; West) |

Son of Eutropia, a daughter of Constantius I. Proclaimed emperor in Rome in opposition to Magnentius | Unknown – 30 June 350 Captured and executed by supporters of Magnentius[135] |

|

Julian "the Apostate" Flavius Claudius Julianus |

3 November 361 – 26 June 363 (1 year, 7 months and 23 days) |

Cousin and heir of Constantius II, acclaimed by the Gallic army around February 360; entered Constantinople on 11 December 361 | 331 – 26 June 363 (aged 32) Last non-Christian emperor. Mortally wounded during a campaign against Persia[136] |

|

Jovian Jovianus[q] |

27 June 363 – 17 February 364 (7 months and 21 days) |

Commander of imperial household guard; acclaimed by the army after Julian's death | 330/331 – 17 February 364 (aged 33) Died before reaching the capital, possibly due to inhaling toxic fumes or indigestion. Last emperor to rule the whole Empire during their entire reign[138] |

Valentinianic dynasty (364–392)

| Portrait | Name[r] | Reign | Succession | Life details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Valentinian I "the Great" Valentinianus |

25/26 February 364 – 17 November 375 (11 years, 8 months and 23 days) Whole; then West |

General; proclaimed emperor by the army after Jovian's death | 321 – 17 November 375 (aged 54) Last emperor to cross the Rhine into Germania. Died of a stroke while yelling at envoys[140] |

|

Valens | 28 March 364 – 9 August 378 (14 years, 4 months and 12 days; East) |

Brother of Valentinian I, made eastern emperor by his brother (Valentinian retaining the west) | c. 328 – 9 August 378 (aged nearly 50) Killed at the Battle of Adrianople[141] |

|

Procopius (#) | 28 September 365 – 27 May 366 (7 months and 29 days; East) |

Maternal cousin of Julian; revolted against Valens and captured Constantinople, where the people proclaimed him emperor | 326 – 27/28 May 366 (aged 40) Deposed, captured and executed by Valens[142] |

|

Gratian Gratianus |

17 November 375 – 25 August 383 (7 years, 9 months and 8 days; West) |

Son of Valentinian I; proclaimed western co-emperor on 24 August 367, at age 8. Emperor in his own right after Valentinian's death | 18 April 359 – 25 August 383 (aged 24) Killed by Andragathius, an officer of Magnus Maximus[143] |

|

Magnus Maximus (#) | 25 August 383 – 28 August 388 (5 years and 3 days; West) with Victor (383/387–388)[s] |

General, related to Theodosius I; proclaimed emperor by the troops in Britain. Briefly recognized by Theodosius I and Valentinian II | Unknown – 28 August 388 Defeated by Theodosius I at the Battle of Save, executed after surrendering[145] |

|

Valentinian II Valentinianus |

28 August 388 – 15 May 392 (3 years, 8 months and 17 days; West) |

Son of Valentinian I, proclaimed co-emperor on 22 November 375, at age 4. Sole western ruler after the defeat of Magnus Maximus in 388 | 371 – 15 May 392 (aged 20/21) Dominated by regents and co-emperors his entire reign. Probably suicide, possibly killed by Arbogast[146] |

|

Eugenius (#) | 22 August 392 – 6 September 394 (2 years and 15 days; West) |

Teacher of Latin grammar and rhetoric, secretary of Valentinian II. Proclaimed emperor by Arbogast | Unknown – 6 September 394 Defeated by Theodosius I at the Battle of the Frigidus and executed[147] |

Theodosian dynasty (379–457)

| Portrait | Name | Reign | Succession | Life details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Theodosius I "the Great" |

19 January 379 – 17 January 395 (15 years, 11 months and 29 days) East; then whole |

Retired general; proclaimed eastern emperor by Gratian. Ruler of the entire empire after Valentinian II's death | 11 January 346/347 – 17 January 395 (aged 48/49) Last emperor to briefly rule over the two halves of the Empire after the Battle of the Frigidus. Died of natural causes[148] |

|

Arcadius | 17 January 395 – 1 May 408 (13 years, 3 months and 14 days; East) |

Son of Theodosius I; co-emperor since 16 January 383. Emperor in the east | 377 – 1 May 408 (aged 31) Died of natural causes[149] |

|

Honorius | 17 January 395 – 15 August 423 (28 years, 6 months and 29 days; West) |

Son of Theodosius I; co-emperor since 23 January 393. Emperor in the west | 9 September 384 – 15 August 423 (aged 38) Reigned under several successive regencies. Died of edema[150] |

|

Constantine III (#) Flavius Claudius Constantinus |

407 – 411 (4 years; West) with Constans (409–411)[s] |

Common soldier, proclaimed emperor by the troops in Britain. Recognized by Honorius in 409. Emperor in the west | Unknown – 411 (before 18 September) Surrendered to Constantius, a general of Honorius, and abdicated. Sent to Italy but murdered on the way[151] |

|

Theodosius II | 1 May 408 – 28 July 450 (42 years, 2 months and 27 days; East) |

Son of Arcadius; co-emperor since 10 January 402. Emperor in the east | 10 April 401 – 28 July 450 (aged 49) Died of a fall from his horse[152] |

|

Priscus Attalus (#) | Late 409 – summer 410 (less than a year; Italy) |

A leading member of the Senate, proclaimed emperor by Alaric after the Sack of Rome. Emperor in the west | Unknown lifespan Deposed by Alaric after reconciling with Honorius. Tried to claim the throne again 414–415 but was defeated and forced into exile; fate unknown[153] |

|

Constantius III | 8 February – 2 September 421 (6 months and 25 days; West) |

Prominent general under Honorius and husband of Galla Placidia, a daughter of Theodosius I. Made co-emperor by Honorius. Emperor in the west | Unknown – 2 September 421 De facto ruler since 411; helped Honorius defeat numerous usurpers & foreign enemies. Died of illness[154] |

|

Johannes (#) | 20 November 423 – c. May 425 (1 year and a half; West) |

Senior civil servant, seized power in Rome and the west after Theodosius II delayed in nominating a successor of Honorius | Unknown – c. May 425 Captured by the forces of Theodosius II, brought to Constantinople and executed[155] |

|

Valentinian III Placidus Valentinianus |

23 October 425 – 16 March 455 (29 years, 4 months and 21 days; West) |

Son of Constantius III, grandson of Theodosius I and great-grandson of Valentinian I, installed as emperor of the west by Theodosius II | 2 July 419 – 16 March 455 (aged 35) Faced the invasion of the Huns. Murdered by Optelas and Thraustelas, retainers of Aetius[156] |

|

Marcian Marcianus |

25 August 450 – 27 January 457 (6 years, 5 months and 2 days; East) |

Soldier and official, proclaimed emperor after marrying Pulcheria, a daughter of Arcadius. Emperor in the east | 391/392 – 27 January 457 (aged 65) Died after a prolonged period of illness[157] |

Last western emperors (455–476)

| Portrait | Name | Reign | Succession | Life details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Petronius Maximus | 17 March – 31 May 455 (2 months and 14 days) |

General and civil official, murdered Valentinian III and married his widow, Licinia Eudoxia | Unknown – 31 May 455 Killed by a mob while fleeing during the Vandalic sack of Rome[158] |

|

Avitus Eparchius Avitus |

9 July 455 – 17 October 456 (1 year, 3 months and 8 days) |

General; proclaimed emperor by the Visigoths and Gallo-Romans after the death of Petronius Maximus | Unknown – 456/457 Defeated and deposed by the magister militum Ricimer, became a bishop. Died shortly after of either natural causes, strangulation, or being starved to death[159] |

|

Majorian Julius Valerius Majorianus |

28 December 457 – 2 August 461 (3 years, 7 months and 5 days) |

General; proclaimed by the army, backed by Ricimer | Unknown – 7 August 461 Reconquered Gaul, Hispania and Dalmatia. Deposed and executed by Ricimer[160] |

|

Libius Severus (Severus III) |

19 November 461 – 14 November 465 (3 years, 11 months and 26 days) |

Proclaimed emperor by Ricimer | Unknown – 14 November 465 Died of natural causes[161] |

|

Anthemius Procopius Anthemius |

12 April 467 – 11 July 472 (5 years, 2 months and 29 days) |

General; great-grandson of Procopius, a cousin of Julian, and husband of Marcia Euphemia, a daughter of Marcian. Proclaimed western emperor by Leo I | Unknown – 11 July 472 The last effective emperor of the West. Murdered by Gundobad after a civil war with Ricimer[162] |

|

Olybrius Anicius Olybrius |

c. April – 2 November 472 (c. 7 months) |

Husband of Placidia, a daughter of Valentinian III. Proclaimed emperor by Ricimer | Unknown – 2 November 472 Died of dropsy[163] |

|

Glycerius | 3/5 March 473 – 24 June 474 (1 year, 3 months and 19/21 days) |

General; proclaimed emperor by Gundobad | Unknown lifespan Deposed by Julius Nepos and made a bishop, subsequent fate unknown[164] |

|

Julius Nepos | 24 June 474 – 28 August 475 (1 year, 2 months and 4 days) August 475 – 9 May 480 (4 years and 8 months, in Dalmatia) |

General; married to a relative of Verina, the wife of the eastern emperor Leo I. Installed as western emperor by Leo | Unknown – 9 May 480 Fled to Dalmatia in the face of an attack by his magister militum Orestes. Continued to claim to be emperor in exile. Murdered by his retainers[165] |

|

Romulus "Augustulus" Romulus Augustus |

31 October 475 – 4 September 476 (10 months and 4 days) |

Proclaimed emperor by his father, the magister militum Orestes | Roughly 465 – after 507/511? The last western emperor. Deposed by the Germanic general Odoacer and retired. Possibly alive as late as 507 or 511; fate unknown[166] |

Later Eastern emperors (457–1453)

Leonid dynasty (457–518)

| Portrait | Name | Reign | Succession | Life details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

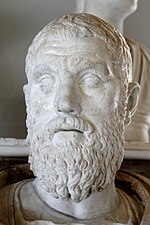

Leo I "Megas" | 7 February 457 – 18 January 474 (16 years, 11 months and 11 days) |

Low-ranking army officer; chosen by the magister militum Aspar to succeed Marcian | 400/401 – 18 January 474 (aged 73) First emperor to be crowned by the Patriarch of Constantinople. Died of dysentery[167] |

|

Leo II "the Younger" | 18 January – November 474 (10 months) |

Grandson of Leo I and son of Zeno; co-emperor since 17 November 473 | 467 – November 474 (aged 7) Youngest emperor at the time of his death. Died of illness[168] |

|

Zeno | 29 January 474 – 9 January 475 (11 months and 11 days) |

Husband of Ariadne, a daughter of Leo I, and father of Leo II. Crowned senior co-emperor with the approval of the Senate | 425 – 9 April 491 (aged 65) Fled to Isauria in the face of a Revolt led by his mother-in-law Verina & Basiliscus.[169] |

|

Basiliscus | 9 January 475 – August 476 (1 year and 7 months) with Marcus (475–476)[s] |

Brother of Verina, the wife of Leo I. Proclaimed emperor by his sister in opposition to Zeno and seized Constantinople | Unknown – 476/477 Deposed by Zeno upon his return to Constantinople; imprisoned in a dried-up reservoir and starved to death[170] |

|

Zeno (second reign) |

August 476 – 9 April 491 (14 years and 8 months) |

Retook the throne with the help of general Illus | 425 – 9 April 491 (aged 65) Saw the end of the Western Roman Empire. Died of dysentery or epilepsy[169] |

|

Anastasius I "Dicorus" | 11 April 491 – 9 July 518 (27 years, 2 months and 28 days) |

Government official; chosen by Ariadne, whom he married, to succeed Zeno | 430/431 – 9 July 518 (aged 88) Oldest emperor at the time of his death. Died of natural causes[171] |

Justinian dynasty (518–602)

| Portrait | Name | Reign | Succession | Life details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Justin I Justinus |

9/10 July 518 – 1 August 527 (9 years and 23 days) |

Soldier; proclaimed emperor by the troops after the death of Anastasius I | 450 – 1 August 527 (aged 77) Died of natural causes[172] |

|

Justinian I "the Great" Petrus Sabbatius Justinianus |

1 April 527 – 14 November 565 (38 years, 7 months and 13 days) |

Nephew and adoptive son of Justin I | 482 – 14 November 565 (aged 83) Temporarily reconquered half of the Western Roman Empire, including Rome. Died of natural causes[173] |

|

Justin II Justinus |

14 November 565 – 5 October 578 (12 years, 10 months and 21 days) |

Son of Vigilantia, sister of Justinian I | Unknown – 5 October 578 Lost most of Italy to the Lombards by 570. Suffered an attack of dementia in 574, whereafter the government was run by regents. Died of natural causes[174] |

|

Tiberius II Constantine Tiberius Constantinus |

26 September 578 – 14 August 582 (3 years, 10 months and 19 days) |

Adoptive son of Justin II | Mid-6th century – 14 August 582 Died after a sudden illness, supposedly after accidentally eating bad food[175] |

|

Maurice Mauricius Tiberius |

13 August 582 – 27 November 602 (20 years, 3 months and 14 days) with Theodosius (590–602)[s] |

Husband of Constantina, a daughter of Tiberius II | 539 – 27 November 602 (aged 63) Captured and executed by troops loyal to Phocas[176] |

|

Phocas Focas |

23 November 602 – 5 October 610 (7 years, 10 months and 12 days) |

Centurion in the army; proclaimed emperor by the troops against Maurice | 547 – 5 October 610 (aged 63) Deposed and then beheaded on the orders of Heraclius[177] |

Heraclian dynasty (610–695)

| Portrait | Name | Reign | Succession | Life details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Heraclius Ἡράκλειος[t] |

5 October 610 – 11 February 641 (30 years, 4 months and 6 days) |

Son of Heraclius the Elder, the exarch of Carthage. Led a revolt against Phocas | 574/575 – 11 February 641 (aged 66) Ended the Persian Wars, but suffered the loss of the Levant to the Muslims. Died of natural causes[180] |

|

Heraclius Constantine (Constantine III)[u] Heraclius Constantinus Ἡράκλειος Κωνσταντῖνος |

11 February – 25 May 641 (3 months and 14 days) |

Son of Heraclius; co-emperor since 22 January 613 | 3 May 612 – 25 May 641 (aged 29) Died of tuberculosis[183] |

|

Heraclonas Heraclius, Ἡράκλειος |

25 May – 5 November (?) 641 (5 months and 11 days) with Tiberius-David, son of Heraclius (641)[s] |

Son of Heraclius; co-emperor since 4 July 638. Co-ruler with Constantine and then sole emperor under the regency of his mother Martina | 626 – unknown Deposed, mutilated and exiled, subsequent fate unknown[184] |

|

Constans II "the Bearded" Constantinus, Κωνσταντῖνος |

September 641 – 15 July 668 (26 years and 10 months) |

Son of Heraclius Constantine; proclaimed co-emperor by Heraclonas at age 11 | 7 November 630 – 15 July 668 (aged 37) Lost Egypt in 641. Murdered in Sicily while bathing by supporters of Mezezius[185] |

|

Constantine IV Constantinus, Κωνσταντῖνος |

September 668 – 10 July (?) 685 (16 years and 10 months) with Heraclius and Tiberius, sons of Constans II (659–681)[s] |

Son of Constans II; co-emperor since 13 April 654 | Roughly 650 – 10 July (?) 685 (aged about 35) Defeated the First Arab Siege of Constantinople. Died of dysentery[186] |

|

Justinian II "Rhinotmetus" Justinianus, Ἰουστινιανός |

July 685 – 695 (10 years) |

Son of Constantine IV | 668/669 – 4 November 711 (aged 42) Deposed and mutilated (hence his nickname, "Slit-nosed") by Leontius in 695; returned to the throne in 705[187] |

Twenty Years' Anarchy (695–717)

| Portrait | Name | Reign | Succession | Life details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Leontius Λέων(τιος) |

695 – 698 (3 years) |

General; deposed Justinian II | Unknown – 15 February (?) 706 Lost Africa & Carthage to the Muslims. Deposed by Tiberius III in 698 and later executed by Justinian II in 706[188] |

|

Tiberius III Τιβέριος |

698 – 21 August (?) 705 (7 years) |

General; proclaimed emperor by the troops against Leontius | Unknown – 15 February (?) 706 Deposed and later executed by Justinian II alongside Leontius[189] |

|

Justinian II "Rhinotmetus" Justinianus, Ἰουστινιανός (second reign) |

21 August (?) 705 – 4 November 711 (6 years, 2 months and 14 days) with Tiberius, son of Justinian II (706–711)[s] |

Retook the throne with the aid of the Khazars | 668/669 – 4 November 711 (aged 42) Killed by supporters of Philippicus after fleeing Constantinople[190] |

|

Philippicus Filepicus, Φιλιππικός |

4 November 711 – 3 June 713 (1 year, 6 months and 30 days) |

General; proclaimed emperor by the troops against Justinian II | Unknown – 20 January 714/715 Deposed and blinded in favor of Anastasius II, later died of natural causes[191] |

|

Anastasius II Artemius Anastasius Ἀρτέμιος Ἀναστάσιος |

4 June 713 – fall 715 (less than 2 years) |

Senior court official, proclaimed emperor after the deposition of Philippicus | Unknown – 1 June 719 Abdicated to Theodosius III after a six-month civil war, becoming a monk. Beheaded by Leo III after an attempt to retake the throne[192] |

|

Theodosius III Θεοδόσιος |

Fall 715 – 25 March 717 (less than 2 years) |

Tax-collector, possibly son of Tiberius III; proclaimed emperor by the troops against Anastasius II | Unknown lifespan Deposed by Leo III, whereafter he became a monk. His subsequent fate is unknown.[193] |

Isaurian (Syrian) dynasty (717–802)

| Portrait | Name | Reign | Succession | Life details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Leo III "the Isaurian" Λέων[v] |

25 March 717 – 18 June 741 (24 years, 2 months and 24 days) |

General; deposed Theodosius III | c. 685 – 18 June 741 (aged approx. 56) Ended Muslim expansion in Anatolia. Died of dropsy[194] |

|

Constantine V "Copronymus" Κωνσταντῖνος |

18 June 741 – 14 September 775 (34 years, 2 months and 27 days) |

Son of Leo III; co-emperor since 31 March 720 | 718 – 14 September 775 (aged 57) Last emperor to rule over Rome. Died of a fever[195] |

|

Artabasdos (#) Ἀρτάβασδος |

June 741 – 2 November 743 (2 years and 5 months) with Nikephoros, son of Artabasdos (741–743) |

Husband of Anna, a daughter of Leo III. Revolted against Constantine V and briefly ruled at Constantinople | Unknown lifespan Deposed and blinded by Constantine V, relegated to a monastery where he died of natural causes[196] |

|

Leo IV "the Khazar" Λέων |

14 September 775 – 8 September 780 (4 years, 11 months and 25 days) |

Son of Constantine V; co-emperor since 6 June 751 | 25 January 750 – 8 September 780 (aged 30) Died of a fever[197] |

|

Constantine VI Κωνσταντῖνος |

8 September 780 – 19 August 797 (16 years, 11 months and 11 days) |

Son of Leo IV; co-emperor since 14 April 776 | 14 January 771 – before 805 (aged less than 34) Last emperor to be recognized in the West. Deposed, blinded and exiled by Irene[198] |

|

Irene Εἰρήνη |

19 August 797 – 31 October 802 (5 years, 2 months and 12 days) |

Widow of Leo IV and former regent of Constantine VI. Became co-ruler in 792. Dethroned and blinded her son Constantine in 797, becoming the first female ruler of the empire | c. 752 – 9 August 803 (aged approx. 51) Deposed by Nikephoros I and exiled to Lesbos, where she died of natural causes[199] |

Nikephorian dynasty (802–813)

| Portrait | Name | Reign | Succession | Life details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Nikephoros I "the Logothete" Νικηφόρος |

31 October 802 – 26 July 811 (8 years, 8 months and 26 days) |

Court official; proclaimed emperor in opposition to Irene | c. 760 – 26 July 811 (aged approx. 51) Killed at the Battle of Pliska[200] |

|

Staurakios Σταυράκιος |

28 July – 2 October 811 (2 months and 4 days) |

Son of Nikephoros I; co-emperor since 25 December 803. Proclaimed emperor after the death of his father | 790s – 11 January 812 (in his late teens) Wounded at Pliska; abdicated in favor of Michael I and became a monk[201] |

|

Michael I Rangabe Μιχαὴλ |

2 October 811 – 11 July 813 (1 year, 9 months and 9 days) with Theophylact and Staurakios, sons of Michael I (811–813)[s] |

Husband of Prokopia, a daughter of Nikephoros I | c. 770 – 11 January 844 (aged approx. 74) Abdicated in 813 in favor of Leo V after suffering a defeat at the Battle of Versinikia and retired as a monk[202] |

|

Leo V "the Armenian" Λέων |

11 July 813 – 25 December 820 (7 years, 5 months and 14 days) with Constantine Symbatios (813–820)[s] |

General; proclaimed emperor after the Battle of Versinikia | c. 775 – 25 December 820 (aged approx. 45) Murdered while in church by supporters of Michael II[203] |

Amorian dynasty (820–867)

| Portrait | Name | Reign | Succession | Life details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Michael II "the Amorian" Μιχαὴλ |

25 December 820 – 2 October 829 (8 years, 9 months and 7 days) |

General sentenced to execution by Leo V; proclaimed emperor by Leo V's assassins and crowned by Patriarch Theodotus I on the same day | c. 770 – 2 October 829 (aged approx. 59) Saw the beginning of the Muslim conquest of Sicily. Died of kidney failure[205] |

|

Theophilos Θεόφιλος |

2 October 829 – 20 January 842 (12 years, 3 months and 18 days) with Constantine (c. 834–835)[s] |

Son of Michael II; co-emperor since 12 May 821 | 812/813 – 20 January 842 (aged 30) Died of dysentery[206] |

|

Theodora (§) Θεοδώρα |

20 January 842 – 15 March 856 (14 years, 1 month and 24 days) with Thekla (842–856)[s] |

Widow of Theophilos; ruler in her own right during the minority of their son Michael III | c. 815 – c. 867 (aged approx. 52) Deposed by Michael III in 856, later died of natural causes[207] |

|

Michael III "the Drunkard" Μιχαὴλ |

20 January 842 – 24 September 867 (25 years, 8 months and 4 days) |

Son of Theophilos; co-emperor since 16 May 840. Ruled under his mother's regency until 15 March 856 | 19 January 840 – 24 September 867 (aged 27) The youngest emperor. Murdered by Basil I and his supporters[208] |

Macedonian dynasty (867–1056)

| Portrait | Name | Reign | Succession | Life details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Basil I "the Macedonian" Βασίλειος |

24 September 867 – 29 August 886 (18 years, 11 months and 5 days) with Constantine (868–879)[s] |

General; proclaimed co-emperor by Michael III on 26 May 866 and became senior emperor after Michael's murder | 811, 830 or 836 – 29 August 886 (aged approx. 50, 56 or 75) Captured Bari in 876 & Taranto in 880. Died after a hunting accident[209] |

|

Leo VI "the Wise" Λέων |

29 August 886 – 11 May 912 (25 years, 8 months and 12 days) |

Son of Basil I or illegitimate son of Michael III; crowned co-emperor on 6 January 870 | 19 September 866 – 11 May 912 (aged 45) Conquered Southern Italy but lost the remnants of Sicily in 902. Died of an intestinal disease[210] |

|

Alexander Αλέξανδρος |

11 May 912 – 6 June 913 (1 year and 26 days) |

Son of Basil I; co-emperor since September or October 879 | 23 November 870 – 6 June 913 (aged 42) Died of illness, possibly testicular cancer[211] |

|

Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus Κωνσταντῖνος |

6 June 913 – 9 November 959 (46 years, 5 months and 3 days) |

Son of Leo VI; co-emperor since 15 May 908. Successively dominated by regents and co-emperors until 27 January 945, when he deposed Romanos I's sons | 17/18 May 905 – 9 November 959 (aged 54) Saw the beginning of renewed expansion in the East against the Arabs. Remembered for his numerous writings. Died of natural causes[212] |

|

Romanos I Lekapenos Ῥωμανὸς |

17 December 920 – 20 December 944 (24 years and 3 days) with Christopher (921–931), Stephen and Constantine Lekapenos (924–945)[s] |

Overthrew Constantine VII's regency, married him to his daughter Helena and was made senior co-emperor. Made several sons co-emperors to curb Constantine VII's authority | c. 870 – 15 June 948 (aged approx. 78) Deposed by his sons Stephen and Constantine. Died of natural causes in exile as a monk[213] |

| Romanos II Ῥωμανὸς |

9 November 959 – 15 March 963 (3 years, 4 months and 6 days) |

Son of Constantine VII and grandson of Romanos I; co-emperor since 6 April 945 | 938 – 15 March 963 (aged 24/25) Reconquered Crete in 961. Died of exhaustion on a hunting trip[214] | |

|

Nikephoros II Phokas Νικηφόρος |

16 August 963 – 11 December 969 (6 years, 3 months and 25 days) |

General; proclaimed emperor on 2 July 963 against the unpopular Joseph Bringas (regent for the young sons of Romanos II), entered Constantinople on 16 August 963. Married Theophano, the widow of Romanos II | c. 912 – 11 December 969 (aged approx. 57) Reconquered Cilicia & Antioch. Murdered in a conspiracy involving his former supporters (including John I Tzimiskes) and Theophano[215] |

|

John I Tzimiskes Ἰωάννης |

11 December 969 – 10 January 976 (6 years and 30 days) |

Nephew of Nikephoros II, took his place as senior co-emperor | c. 925 – 10 January 976 (aged approx. 50) Reconquered Eastern Thrace from the First Bulgarian Empire. Possibly poisoned by Basil Lekapenos[216] |

|

Basil II "the Bulgar-Slayer" Βασίλειος |

10 January 976 – 15 December 1025 (49 years, 11 months and 5 days) |

Son of Romanos II; co-emperor since 22 April 960, briefly reigned as senior emperor in March–August 963. Succeeded as senior emperor upon the death of John I | 958 – 15 December 1025 (aged 67) The longest-reigning emperor; best known for his reconquest of Bulgaria. Died of natural causes[217] |

|

Constantine VIII Κωνσταντῖνος |

15 December 1025 – 12 November 1028 (2 years, 10 months and 28 days) |

Son of Romanos II and brother of Basil II; co-emperor since 30 March 962 | 960 – 12 November 1028 (aged 68) De jure longest-reigning emperor. Died of natural causes[218] |

|

Romanos III Argyros Ῥωμανὸς |

12 November 1028 – 11 April 1034 (5 years, 4 months and 30 days) |

Husband of Zoë, a daughter of Constantine VIII | c. 968 – 11 April 1034 (aged approx. 66) Temporarily reconquered Edessa in 1031. Possibly drowned on Zoë's orders[219] |

|

Michael IV "the Paphlagonian" Μιχαὴλ |

12 April 1034 – 10 December 1041 (7 years, 7 months and 28 days) |

Lover of Zoë, made emperor after their marriage following Romanos III's death | c. 1010 – 10 December 1041 (aged approx. 31) Died of epilepsy[220] |

|

Michael V "Kalaphates" Μιχαὴλ |

13 December 1041 – 21 April 1042 (4 months and 8 days) |

Nephew and designated heir of Michael IV, proclaimed emperor by Zoë three days after Michael IV's death | c. 1015 – unknown Deposed in a popular uprising after attempting to sideline Zoë, blinded and forced to become a monk[221] |

|

Zoë Porphyrogenita Ζωή |

21 April – 11 June 1042 (1 month and 21 days) |

Daughter of Constantine VIII and widow of Romanos III and Michael IV. Ruled in her own right from Michael V's deposition until her marriage to Constantine IX. | c. 978 – 1050 (aged approx. 72) Died of natural causes[222] |

|

Theodora Porphyrogenita Θεοδώρα |

21 April – 11 June 1042 (1 month and 21 days) |

Daughter of Constantine VIII and sister of Zoë, proclaimed co-empress during the revolt that deposed Michael V | c. 980 – 31 August 1056 (aged approx. 76) Sidelined after Zoë's marriage to Constantine IX, returned to the throne in 1055[223] |

|

Constantine IX Monomachos Κωνσταντῖνος Μονομάχος[x] |

11 June 1042 – 11 January 1055 (12 years and 7 months) |

Husband of Zoë, crowned the day after their marriage | c. 1006 – 11 January 1055 (aged approx. 49) Died of natural causes[225] |

|

Theodora Porphyrogenita Θεοδώρα (second reign) |

11 January 1055 – 31 August 1056 (1 year, 7 months and 20 days) |

Claimed the throne again after Constantine IX's death as the last living member of the Macedonian dynasty | c. 980 – 31 August 1056 (aged approx. 76) Died of natural causes[223] |

|

Michael VI Bringas "Stratiotikos" Μιχαήλ[x] |

22 August 1056 – 30 August 1057 (1 year and 8 days) |

Proclaimed emperor by Theodora on her deathbed | 980s/990s – c. 1057 (in his sixties) Deposed in a revolt, retired to a monastery and died soon afterwards[226] |

|

Isaac I Komnenos Ἰσαάκιος Κομνηνός |

1 September 1057 – 22 November 1059 (2 years, 2 months and 21 days) |

General, proclaimed emperor on 8 June 1057 in opposition to Michael VI | c. 1007 – 31 May/1 June 1060 (aged approx. 53) Abdicated to Constantine X due to illness and hostile courtiers, became a monk[227] |

Doukas dynasty (1059–1078)

| Portrait | Name | Reign | Succession | Life details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Constantine X Doukas Κωνσταντῖνος Δούκας |

23 November 1059 – 23 May 1067 (7 years and 6 months) |

Designated as emperor by Isaac I Komnenos during his abdication | c. 1006 – 23 May 1067 (aged approx. 61) Lost nearly all Italian territories to the Normans. Died of natural causes[228] |

|

Eudokia Makrembolitissa Εὐδοκία Μακρεμβολίτισσα (§) |

23 May – 31 December 1067 (7 months and 8 days) |

Widow of Constantine X; ruler in her own right on behalf of their sons until her marriage to Romanos IV. Briefly resumed her regency in September 1071 | c. 1030 – after 1078 Became a nun in November 1071 and later died of natural causes[229] |

|

Romanos IV Diogenes Ῥωμανὸς Διογένης |

1 January 1068 – 26 August 1071 (3 years, 7 months and 25 days) with Leo and Nikephoros Diogenes (c. 1070–71)[s][y] |

Husband of Eudokia. Regent and senior co-emperor together with Constantine X's and Eudokia's children | c. 1032 – 4 August 1072 (aged approx. 40) Captured at Manzikert by the Seljuk Turks. After his release blinded on 29 June 1072 by John Doukas, later dying of his wounds[231] |

|

Michael VII Doukas "Parapinakes" Μιχαὴλ Δούκας |

1 October 1071 – 24/31 March 1078 (6 years, 5 months and 23/30 days) with Konstantios (1060–1078), Andronikos (1068–1070s) and Constantine Doukas (1074–78; 1st time)[s] |

Son of Constantine X; made co-emperor in 1060 with Eudokia and Romanos IV. Proclaimed sole emperor after Romanos' defeat at the Battle of Manzikert | c. 1050 – c. 1090 (aged approx. 40) Lost nearly all of Anatolia to the Turks. Forced to become a monk after a popular uprising. Died of natural causes several years later[232] |

|

Nikephoros III Botaneiates Νικηφόρος Βοτανειάτης |

3 April 1078 – 1 April 1081 (2 years, 11 months and 29 days) |

General; revolted against Michael VII on 2 July or 2 October 1077 and entered Constantinople on 27 March or 3 April. Married Maria of Alania, the former wife of Michael VII | 1001/1002 – c. 1081 (aged approx. 80) Abdicated after Alexios I captured Constantinople, became a monk and died of natural causes, probably later in the same year[233] |

Komnenos dynasty (1081–1185)

| Portrait | Name | Reign | Succession | Life details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Alexios I Komnenos Ἀλέξιος Κομνηνός |

1 April 1081 – 15 August 1118 (37 years, 4 months and 14 days) with Constantine Doukas (1081–1087; 2nd time)[s] |

Nephew of Isaac I, also husband of Irene Doukaina, a grand-niece of Constantine X. General; revolted against Nikephoros III on 14 February 1081. Seized Constantinople on 1 April; crowned on 4 April | c. 1057 – 15 August 1118 (aged approx. 61) Started the Crusades & the reconquest of Anatolia. Died of natural causes[234] |

|

John II Komnenos "the Good" Ἰωάννης Κομνηνός |

15 August 1118 – 8 April 1143 (24 years, 7 months and 24 days) with Alexios Komnenos, son of John II (1119–1142)[s] |

Son of Alexios I, co-emperor since about September 1092 | 13 September 1087 – 8 April 1143 (aged 55) Reconquered most of Anatolia by the time of his death. Died of injuries sustained in a hunting accident, possibly assassinated (perhaps involving Raymond of Poitiers or supporters of Manuel I)[235] |

|

Manuel I Komnenos "the Great" Μανουὴλ Κομνηνός |

8 April 1143 – 24 September 1180 (37 years, 5 months and 16 days) |

Youngest son and allegedly designated heir of John II on his deathbed, crowned in November 1143 after a few months of having to establish his rights | 28 November 1118 – 24 September 1180 (aged 61) Last emperor to attempt reconquests in the west. Died of natural causes[236] |

|

Alexios II Komnenos Ἀλέξιος Κομνηνός |

24 September 1180 – c. September 1183 (3 years) |

Son of Manuel I; co-emperor since 1171 | 14 September 1169 – c. September 1183 (aged 14) Strangled on the orders of Andronikos I, body thrown in the sea[237] |

|

Andronikos I Komnenos "Misophaes" Ἀνδρόνικος Κομνηνός |

c. September 1183 – 12 September 1185 (2 years) with John Komnenos, son of Andronikos I (1183–1185)[s] |

Son of Isaac Komnenos, a son of Alexios I. Overthrew the regency of Alexios II in April 1182, crowned co-emperor in 1183 and shortly thereafter had Alexios II murdered | c. 1118/1120 – 12 September 1185 (aged 64–67) Overthrown by Isaac II, tortured and mutilated in the imperial palace, then slowly dismembered alive by a mob in the Hippodrome[238] |

Angelos dynasty (1185–1204)

| Portrait | Name | Reign | Succession | Life details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Isaac II Angelos Ἰσαάκιος Κομνηνός Ἄγγελος |

12 September 1185 – 8 April 1195 (9 years, 6 months and 27 days) |

Great-grandson of Alexios I. Resisted an order of arrest issued by Andronikos I, after which he was proclaimed emperor by the people of Constantinople. Captured and killed Andronikos I | c. 1156 – January 1204 (aged 47) Suffered the loss of Bulgaria. Overthrown and blinded by Alexios III in 1195, reinstalled in 1203[239] |

|

Alexios III Angelos Ἀλέξιος Κομνηνός[z] |

8 April 1195 – 17/18 July 1203 (8 years, 3 months and 10 days) |

Elder brother of Isaac II, overthrew and blinded his brother | c. 1156 – 1211/1212 (aged approx. 58) Fled after brief resistance against the Fourth Crusade. Died a natural death after being captured and forced to become a monk by Theodore I[241] |

|

Alexios IV Angelos Ἀλέξιος Ἄγγελος |

19 July 1203 – 27 January 1204 (6 months and 8 days) |

Son of Isaac II, overthrew Alexios III with the help of the crusaders as part of the Fourth Crusade, then named co-emperor alongside his blinded father | c. 1182/1183 – c. 8 February 1204 (aged approx. 21) Deposed and imprisoned by Alexios V, then strangled in prison[242] |

|

Isaac II Angelos Ἰσαάκιος Κομνηνός Ἄγγελος (second reign) |

19 July 1203 – 27 January 1204 (6 months and 8 days) |

Freed from imprisonment during the Fourth Crusade by courtiers and reinstated as ruler after Alexios III abandoned the defense of Constantinople | c. 1156 – January 1204 (aged 47) Became senile or demented and died of natural causes shortly before Alexios V's coup[239] |

|

Alexios V Doukas "Mourtzouphlos" Ἀλέξιος Δούκας |

27/28 January – 12 April 1204 (2 months and 16 days) |

Seized power through a palace coup, son-in-law of Alexios III. | c. 1139 – c. late November 1204 (aged approx. 65) Fled during the sack of Constantinople. Blinded by Alexios III, later captured by crusader Thierry de Loos and thrown from the Column of Theodosius[243] |

Laskaris dynasty (1205–1261)

- Note: Roman rule in Constantinople was interrupted with the capture and sack of the city by the crusaders in 1204, which led to the establishment of the Frankokratia. Though the crusaders created a new line of Latin emperors in the city, modern historians recognize the line of emperors of the Laskaris dynasty, reigning in Nicaea, as the legitimate Roman emperors during this period because the Nicene Empire eventually retook Constantinople.[23] For other lines of claimant emperors, see List of Trapezuntine emperors and List of Thessalonian emperors.

| Portrait | Name | Reign | Succession | Life details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Theodore I Laskaris Θεόδωρος Κομνηνὸς Λάσκαρις |

c. May 1205 – November 1221 (16 years and 6 months) with Nicholas Laskaris (1208–1210)[s] |

Husband of Anna Komnene Angelina, a daughter of Alexios III. Organized resistance against the Latin Empire in Nicaea and proclaimed emperor in 1205 after the Battle of Adrianople; crowned by Patriarch Michael IV on 6 April 1208. | c. 1174 – November 1221 (aged approx. 47) Died of natural causes[244] |

|

John III Vatatzes Ἰωάννης Δούκας Βατάτζης |

c. December 1221 – 3 November 1254 (32 years and 11 months) |

Husband of Irene Laskarina, a daughter of Theodore I | c. 1192 – 3 November 1254 (aged approx. 62) Started Nicaean expansionism. Died of natural causes[245] |

|

Theodore II Laskaris Θεόδωρος Δούκας Λάσκαρις |

3 November 1254 – 16 August 1258 (3 years, 9 months and 13 days) |

Son of John III and grandson of Theodore I, co-emperor since about 1235 | November 1221 – 16 August 1258 (aged 36) Died of epilepsy[246] |

|

John IV Laskaris Ἰωάννης Δούκας Λάσκαρις |

16 August 1258 – 25 December 1261 (3 years, 4 months and 9 days) |

Son and co-emperor of Theodore II | 25 December 1250 – c. 1305 (aged approx. 55) Blinded, deposed and imprisoned by Michael VIII Palaiologos in 1261, died in captivity several decades later[247] |

Palaiologos dynasty (1259–1453)

| Portrait | Name | Reign | Succession | Life details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Michael VIII Palaiologos Μιχαὴλ Δούκας Ἄγγελος Κομνηνὸς Παλαιολόγος |

1 January 1259 – 11 December 1282 (23 years, 11 months and 10 days) |

Great-grandson of Alexios III; became regent for John IV in 1258 and crowned co-emperor in 1259. Regained Constantinople on 25 July 1261, entered the city on 15 August. Became sole ruler after deposing John IV on 25 December | 1224/1225 – 11 December 1282 (aged 57/58) Died of dysentery[248] |

|

Andronikos II Palaiologos Ἀνδρόνικος Δούκας Ἄγγελος Κομνηνὸς Παλαιολόγος |

11 December 1282 – 24 May 1328 (45 years, 5 months and 13 days) |

Son of Michael VIII; named co-emperor shortly after 1261, crowned on 8 November 1272 | 25 March 1259 – 13 February 1332 (aged 72) Deposed by his grandson Andronikos III in 1328 and became a monk, dying of natural causes four years later[249] |

|

Michael IX Palaiologos (§) Μιχαὴλ Δούκας Ἄγγελος Κομνηνὸς Παλαιολόγος |

21 May 1294 – 12 October 1320 (26 years, 4 months and 21 days) |

Son and co-ruler of Andronikos II, named co-emperor in 1281, crowned on 21 May 1294 | 17 April 1277/1278 – 12 October 1320 (aged 42/43) Allegedly died of grief due to the accidental murder of his second son, probably died of natural causes[250] |

|

Andronikos III Palaiologos Ἀνδρόνικος Δούκας Ἄγγελος Κομνηνός Παλαιολόγος |

24 May 1328 – 15 June 1341 (13 years and 22 days) |

Son of Michael IX, named co-emperor between 1308 and 1313. Fought with his grandfather Andronikos II for power from April 1321 onwards. Crowned emperor on 2 February 1325, became sole emperor after deposing Andronikos II | 25 March 1297 – 15 June 1341 (aged 44) Last Emperor to effectively control Greece. Died of sudden illness, possibly malaria[251] |

| John V Palaiologos Ίωάννης Κομνηνός Παλαιολόγος |

15 June 1341 – 16 February 1391 (49 years, 8 months and 1 day) Details

|

Son of Andronikos III, not formally crowned until 19 November 1341. Dominated by regents until 1354, faced numerous usurpations and civil wars throughout his long reign | 18 June 1332 – 16 February 1391 (aged 58) Reigned almost 50 years, but only held effective power for 33. Lost almost all territories outside Constantinople. Died of natural causes[252] | |

|

John VI Kantakouzenos Ἰωάννης Ἄγγελος Κομνηνὸς Παλαιολόγος Καντακουζηνός |

8 February 1347 – 10 December 1354 (7 years, 10 months and 2 days) with Matthew Kantakouzenos (1353–1357)[s] |

Related to the Palaiologoi through his mother. Proclaimed by the army on 26 October 1341, became regent and senior co-emperor after a lengthy civil war with John V's mother, Anna of Savoy. Entered Constantinople on 8 February, crowned on 21 May 1347 | c. 1295 – 15 June 1383 (aged approx. 88) Deposed by John V in another civil war and retired, becoming a monk. Died of natural causes several decades later[253] |

|

Andronikos IV Palaiologos Ἀνδρόνικος Κομνηνός Παλαιολόγος |

12 August 1376 – 1 July 1379 (2 years, 10 months and 19 days) May 1381 – June 1385 (4 years, in Selymbria) |

Son of John V and grandson of John VI; named co-emperor and heir in 1352, but imprisoned and partially blinded after a failed rebellion in May 1373. Rebelled again and successfully deposed his father in 1376; not formally crowned until 18 October 1377 | 11 April 1348 – 25/28 June 1385 (aged 37) Deposed by John V in 1379; fled to Galata in exile but was restored as co-emperor and heir in May 1381, ruling over Selymbria and the coast of Marmara. Rebelled again in June 1385 but died shortly thereafter[254] |

|

John VII Palaiologos Ίωάννης Παλαιολόγος |

14 April – 17 September 1390 (5 months and 3 days) late 1403 – 22 September 1408 (5 years, in Thessalonica) with Andronikos V Palaiologos (1403–1407)[s] |

Son of Andronikos IV, co-emperor since 1377; usurped the throne from John V in 1390. Deposed shortly thereafter but granted Thessalonica by Manuel II in 1403, from where he once more ruled as emperor until his death | 1370 – 22 September 1408 (aged 38) Ruled Constantinople as regent in 1399–1403 during Manuel II's absence. Died of natural causes[255] |

| Manuel II Palaiologos Μανουὴλ Παλαιολόγος |

16 February 1391 – 21 July 1425 (34 years, 4 months and 5 days) |

Son of John V and grandson of John VI; co-emperor since 25 September 1373 | 27 June 1350 – 21 July 1425 (aged 74) Suffered a stroke in 1422, whereafter the government was run by his son, John VIII. Died of natural causes[256] | |

| John VIII Palaiologos Ίωάννης Παλαιολόγος |

21 July 1425 – 31 October 1448 (23 years, 4 months and 10 days) |

Son of Manuel II; co-emperor by 1407 and full emperor since 19 January 1421 | 18 December 1392 – 31 October 1448 (aged 55) Died of natural causes[257] | |

|

Constantine XI Palaiologos Κωνσταντῖνος Δραγάσης Παλαιολόγος |

6 January 1449 – 29 May 1453 (4 years, 4 months and 23 days) |