Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty

| Treaty Between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on the Elimination of Their Intermediate-Range and Shorter-Range Missiles | |

|---|---|

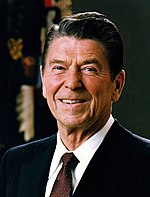

Mikhail Gorbachev and Ronald Reagan sign the INF Treaty. | |

| Type | Nuclear disarmament |

| Signed | 8 December 1987, 1:45 pm.[1] |

| Location | White House, Washington, D.C., United States |

| Effective | 1 June 1988 |

| Condition | Ratification by the Soviet Union and United States |

| Expiration | 2 August 2019 (U.S. withdrawal) |

| Signatories | |

| Parties | |

| Languages | English and Russian |

| Text of the INF Treaty | |

The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF Treaty)[a][b] was an arms control treaty between the United States and the Soviet Union (and its successor state, the Russian Federation). US President Ronald Reagan and Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev signed the treaty on 8 December 1987.[1][2] The US Senate approved the treaty on 27 May 1988, and Reagan and Gorbachev ratified it on 1 June 1988.[2][3]

The INF Treaty banned all of the two nations' nuclear and conventional ground-launched ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, and missile launchers with ranges of 500–1,000 kilometers (310–620 mi) (short medium-range) and 1,000–5,500 km (620–3,420 mi) (intermediate-range). The treaty did not apply to air- or sea-launched missiles.[4][5] By May 1991, the nations had eliminated 2,692 missiles, followed by 10 years of on-site verification inspections.[6]

President Donald Trump announced on 20 October 2018 that he was withdrawing the US from the treaty due to Russian non-compliance,[7][8][9] claiming that Russia had breached the treaty by developing and deploying an intermediate-range cruise missile known as the SSC-8 (Novator 9M729).[10][11] The Trump administration claimed another reason for the withdrawal was to counter a Chinese arms buildup in the Pacific, including within the South China Sea, as China was not a signatory to the treaty.[7][12][13] The US formally suspended the treaty on 1 February 2019,[14] and Russia did so on the following day in response.[15] The United States formally withdrew from the treaty on 2 August 2019.[16]

Background

[edit]In March 1976, the Soviet Union first deployed the RSD-10 Pioneer (called SS-20 Saber in the West) in its European territories; a mobile, concealable intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) with a multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle (MIRV) containing three nuclear 150-kiloton warheads.[17] The SS-20's range of 4,700–5,000 kilometers (2,900–3,100 mi) was great enough to reach Western Europe from well within Soviet territory; the range was just below the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks II (SALT II) Treaty minimum range for an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), 5,500 km (3,400 mi).[18][19][20] The SS-20 replaced the aging SS-4 Sandal and SS-5 Skean, which were seen to pose a limited threat to Western Europe due to their poor accuracy, limited payload (one warhead), lengthy time to prepare to launch, difficulty of concealment, and a lack of mobility which exposed them to pre-emptive NATO strikes ahead of a planned attack.[21] While the SS-4 and SS-5 were seen as defensive weapons, the SS-20 was seen as a potential offensive system.[22]

The United States, then under President Jimmy Carter, initially considered its strategic nuclear weapons and nuclear-capable aircraft to be adequate counters to the SS-20 and a sufficient deterrent against possible Soviet aggression. In 1977, however, Chancellor Helmut Schmidt of West Germany argued in a speech that a Western response to the SS-20 deployment should be explored, a call which was echoed by NATO, given a perceived Western disadvantage in European nuclear forces.[20] Leslie H. Gelb, the US Assistant Secretary of State, later recounted that Schmidt's speech pressured the US into developing a response.[23]

On 12 December 1979, following European pressure for a response to the SS-20, Western foreign and defense ministers meeting in Brussels made the NATO Double-Track Decision.[20] The ministers argued that the Warsaw Pact had "developed a large and growing capability in nuclear systems that directly threaten Western Europe": "theater" nuclear systems (i.e., tactical nuclear weapons).[24] In describing this aggravated situation, the ministers made direct reference to the SS-20 featuring "significant improvements over previous systems in providing greater accuracy, more mobility, and greater range, as well as having multiple warheads". The ministers also attributed the altered situation to the deployment of the Soviet Tupolev Tu-22M strategic bomber, which they believed had much greater performance than its predecessors. Furthermore, the ministers expressed concern that the Soviet Union had gained an advantage over NATO in "Long-Range Theater Nuclear Forces" (LRTNF), and also significantly increased short-range theater nuclear capacity.[25]

The Double-Track Decision involved two policy "tracks". Initially, of the 7,400 theater nuclear warheads, 1,000 would be removed from Europe and the US would pursue bilateral negotiations with the Soviet Union intended to limit theater nuclear forces. Should these negotiations fail, NATO would modernize its own LRTNF, or intermediate-range nuclear forces (INF), by replacing US Pershing 1a missiles with 108 Pershing II launchers in West Germany and deploying 464 BGM-109G Ground Launched Cruise Missiles (GLCMs) to Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom beginning in December 1983.[19][26][27][28]

Negotiations

[edit]Early negotiations: 1981–1983

[edit]The Soviet Union and United States agreed to open negotiations and preliminary discussions, named the Preliminary Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Talks,[19] which began in Geneva, Switzerland, in October 1980. The relations were strained at the time due to the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan which led America to impose sanctions against the USSR. On 20 January 1981, Ronald Reagan was sworn into office after defeating Jimmy Carter in the 1980 United States presidential election. Formal talks began on 30 November 1981, with the US negotiators led by Reagan and those of the Soviet Union by General Secretary, Leonid Brezhnev. The core of the US negotiating position reflected the principles put forth under Carter: any limits placed on US INF capabilities, both in terms of "ceilings" and "rights", must be reciprocated with limits on Soviet systems. Additionally, the US insisted that a sufficient verification regime be put in place.[29]

Paul Nitze, an experienced politician and long-time presidential advisor on defense policy who had participated in the SALT talks, led the US delegation after being recruited by Secretary of State Alexander Haig. Though Nitze had backed the first SALT treaty, he opposed SALT II and had resigned from the US delegation during its negotiation. Nitze was also then a member of the Committee on the Present Danger, a firmly anti-Soviet group composed of conservative Republicans.[23][30] Yuli Kvitsinsky, the second-ranking official at the Soviet embassy in West Germany, headed the Soviet delegation.[22][31][32][33]

On 18 November 1981, shortly before the beginning of formal talks, Reagan made the Zero Option or "zero-zero" proposal.[34] It called for a hold on US deployment of GLCM and Pershing II systems, reciprocated by Soviet elimination of its SS-4, SS-5, and SS-20 missiles. There appeared to be little chance of the Zero Option being adopted due to Soviet opposition, but the gesture was well received by the European public. In February 1982, US negotiators put forth a draft treaty containing the Zero Option and a global prohibition on intermediate- and short-range missiles, with compliance ensured via a stringent, though unspecified, verification program.[31]

Opinion within the Reagan administration on the Zero Option was mixed. Richard Perle, then the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Global Strategic Affairs, was the architect of the plan. Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger, who supported a continued US nuclear presence in Europe, was skeptical of the plan, though eventually accepted it for its value in putting the Soviet Union "on the defensive in the European propaganda war". Reagan later recounted that the "zero option sprang out of the realities of nuclear politics in Western Europe".[34] The Soviet Union rejected the plan shortly after the US tabled it in February 1982, arguing that both the US and USSR should be able to retain intermediate-range missiles in Europe. Specifically, Soviet negotiators proposed that the number of INF missiles and aircraft deployed in Europe by each side be capped at 600 by 1985 and 300 by 1990. Concerned that this proposal would force the US to withdraw aircraft from Europe and not deploy INF missiles, given US cooperation with existing British and French deployments, the US proposed "equal rights and limits"—the US would be permitted to match Soviet SS-20 deployments.[31]

Between 1981 and 1983, American and Soviet negotiators gathered for six rounds of talks, each two months in length—a system based on the earlier SALT talks.[31] The US delegation was composed of Nitze, Major General William F. Burns of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Thomas Graham of the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency (ACDA), and officials from the US Department of State, Office of the Secretary of Defense, and US National Security Council. Colonel Norman Clyne, a SALT talks participant, served as Nitze's chief of staff.[22][35]

There was little convergence between the two sides over these two years. A US effort to separate the question of nuclear-capable aircraft from that of intermediate-range missiles successfully focused attention on the latter, but little clear progress on the subject was made. In the summer of 1982, Nitze and Kvitsinsky took a "walk in the woods" in the Jura Mountains, away from formal negotiations in Geneva, in an independent attempt to bypass bureaucratic procedures and break the negotiating deadlock.[36][22][37] Nitze later said that his and Kvitsinsky's goal was to agree to certain concessions that would allow for a summit meeting between Brezhnev and Reagan later in 1982.[38]

Nitze's offer to Kvitsinsky was that the US would forego deployment of the Pershing II and limit the deployment of GLCMs to 75. The Soviet Union, in return, would also have to limit itself to 75 intermediate-range missile launchers in Europe and 90 in Asia. Due to each GLCM launcher containing four GLCMs and each SS-20 launcher containing three warheads, such an agreement would have resulted in the US having 75 more intermediate-range warheads in Europe than the USSR, though Soviet SS-20s were seen as more advanced and maneuverable than American GLCMs. While Kvitsinsky was skeptical that the plan would be well-received in Moscow, Nitze was optimistic about its chances in Washington.[38] The deal ultimately found little traction in either capital. In the United States, the Office of the Secretary of Defense opposed Nitze's proposal, as it opposed any proposal that would allow the Soviet Union to deploy missiles to Europe while blocking American deployments. Nitze's proposal was relayed by Kvitsinsky to Moscow, where it was also rejected. The plan accordingly was never introduced into formal negotiations.[36][22]

Thomas Graham, a US negotiator, later recalled that Nitze's "walk in the woods" proposal was primarily of Nitze's own design and known beforehand only to Burns and Eugene V. Rostow, the director of ACDA. In a National Security Council meeting following the Nitze-Kvitsinsky walk, the proposal was received positively by the Joint Chiefs of Staff and Reagan. Following protests by Perle, working within the Office of the Secretary of Defense, Reagan informed Nitze that he would not back the plan. The State Department, then led by Haig, also indicated that it would not support Nitze's plan and preferred a return to the Zero Option proposal.[22][37][38] Nitze argued that one positive consequence of the walk in the woods was that the Western European public, which had doubted American interest in arms control, became convinced that the US was participating in the INF negotiations in good faith.[38]

In early 1983, US negotiators indicated that they would support a plan beyond the Zero Option if the plan established equal rights and limits for the US and USSR, with such limits valid worldwide, and excluded British and French missile systems (as well as those of any other third party). As a temporary measure, the US negotiators also proposed a cap of 450 deployed INF warheads around the world for both the United States and Soviet Union. In response, Soviet negotiators proposed that a plan would have to block all US INF deployments in Europe, cover both missiles and aircraft, include third parties, and focus primarily on Europe for it to gain Soviet backing. In the fall of 1983, just ahead of the scheduled deployment of US Pershing IIs and GLCMs, the United States lowered its proposed limit on global INF deployments to 420 missiles, while the Soviet Union proposed "equal reductions": if the US cancelled the planned deployment of Pershing II and GLCM systems, the Soviet Union would reduce its own INF deployment by 572 warheads. In November 1983, after the first Pershing IIs arrived in West Germany, the Soviet Union ended negotiations.[39]

Restarted negotiations: 1985–1987

[edit]

British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher played a key role in brokering the negotiations between Reagan and new Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev in 1986 to 1987.[40]

In March 1986, negotiations between the US and the USSR resumed, covering not only the INF issue, but also the separate Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I) and space issues (Nuclear and Space Talks). In late 1985, both sides were moving towards limiting INF systems in Europe and Asia. On 15 January 1986, Gorbachev announced a Soviet proposal for a ban on all nuclear weapons by 2000, which included INF missiles in Europe. This was dismissed by the United States as a public relations stunt and countered with a phased reduction of INF launchers in Europe and Asia with the target of none by 1989. There would be no constraints on British and French nuclear forces.[41]

A series of meetings in August and September 1986 culminated in the Reykjavík Summit between Reagan and Gorbachev on 11 and 12 October 1986. Both agreed in principle to remove INF systems from Europe and to equal global limits of 100 INF missile warheads. Gorbachev also proposed deeper and more fundamental changes in the strategic relationship. More detailed negotiations extended throughout 1987, aided by the decision of West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl in August to remove the joint US-West German Pershing 1a systems. Initially, Kohl had opposed the total elimination of the Pershing missiles, claiming that such a move would increase his nation's vulnerability to an attack by Warsaw Pact forces.[42] The treaty text was finally agreed in September 1987. On 8 December 1987, the treaty was officially signed by Reagan and Gorbachev at a summit in Washington and ratified the following May in a 93–5 vote by the United States Senate.[43][44]

Contents

[edit]The treaty prohibited both parties from possessing, producing, or flight-testing ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges of 500–5,500 km (310–3,420 mi). Possessing or producing ground-based launchers of those missiles was also prohibited. The ban extended to weapons with both nuclear and conventional warheads, but did not cover air-delivered or sea-based missiles.[45] Existing weapons had to be destroyed, and a protocol for mutual inspection was agreed upon.[45] Each party had the right to withdraw from the treaty with six months' notice, "if it decides that extraordinary events related to the subject matter of this Treaty have jeopardized its supreme interests".[45]

Timeline

[edit]Implementation

[edit]

By the treaty's deadline of 1 June 1991, a total of 2,692 of such weapons had been destroyed, 846 by the US and 1,846 by the Soviet Union.[46] The following specific missiles, their launcher systems, and their transporter vehicles were destroyed:[47]

- United States

- BGM-109G Ground Launched Cruise Missile (decommissioned)

- Pershing 1a (decommissioned)

- Pershing II (decommissioned)

- Soviet Union (listed by NATO reporting name)

- SS-4 Sandal (decommissioned)

- SS-5 Skean (decommissioned)

- SS-12 Scaleboard (decommissioned)

- SS-20 Saber (decommissioned)

- SS-23 Spider (decommissioned)

- SSC-X-4 Slingshot

Treaty after December 1991

[edit]Five months prior to the collapse of the Soviet Union in December 1991, the United States and the Soviet Union completed the dismantling of their intermediate-range missiles on May 28 as outlined by the INF Treaty.[48] After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the United States focused on negotiations with Belarus, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Ukraine to preserve the START 1 treaty that further decreased nuclear armament. The United States considered twelve of the post-Soviet states to be inheritors of the treaty obligations (the three Baltic states are considered to preexist their illegal annexation by the Soviet Union in 1940).[49] The US did not focus immediate attention on the preservation of the INF Treaty because the disarmament of INF missiles already occurred.[50][page needed] Eventually, the US began negotiations to maintain the treaty in the six newly independent states of the former Soviet Union that contained INF sites subject to inspection: Belarus, Kazakhstan, Russia, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan, with Russia being the USSR's official successor state and inheriting its nuclear arsenal.[50][page needed] From these six countries, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Ukraine entered agreements to continue the fulfillment of the INF Treaty.[2] The remaining two states, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, became passive participants in the negotiations with approval from the other participating states due to the presence of a single inspection site in each country.[2] Inspection of INF missile sites continued until May 31, 2001, as stipulated by the 13-year inspection agreement within the treaty.[48] After this period, the United States and Russia continued to share national technical means of verification and notifications to ensure that each state maintained compliance.[48] The treaty states continued to meet at Special Verification Committees after the end of the inspection period. There were 30 total meetings with the final meeting occurring in November 2016 in Geneva, Switzerland with the United States, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Ukraine meeting to discuss compliance obligations.[48]

Initial skepticism and allegations of treaty violations

[edit]In February 2007, Vladimir Putin, the President of the Russian Federation, gave a speech at the Munich Security Conference in which he said the INF Treaty should be revisited to ensure security, as it only restricted Russia and the US but not other countries.[51] The Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation, Army General Yuri Baluyevsky, contemporaneously said that Russia was planning to unilaterally withdraw from the treaty in response to deployment of the NATO missile defence system in Europe and because other countries were not bound to the treaty.[52]

According to US officials, Russia violated the treaty in 2008 by testing the SSC-8 cruise missile, which has a range of 3,000 km (1,900 mi).[53][54] Russia rejected the claim that their SSC-8 missiles violated the treaty, claiming that the SSC-8 has a maximum range of only 480 km (300 mi).[citation needed] In 2013, it was reported that Russia had tested and planned to continue testing two missiles in ways that could violate the terms of the treaty: the road-mobile SS-25 and the newer RS-26 ICBMs.[55] The US representatives briefed NATO on other Russian breaches of the INF Treaty in 2014[56][57] and 2017.[53][58] In 2018, NATO formally supported the US claims and accused Russia of breaking the treaty.[16][59] Russia denied the accusation and Putin said it was a pretext for the US to withdraw from the treaty.[16] A BBC analysis of the meeting that culminated in the NATO statement said that "NATO allies here share Washington's concerns and have backed the US position, thankful perhaps that it includes this short grace period during which Russia might change its mind."[60]

In 2011, Dan Blumenthal of the American Enterprise Institute wrote that the actual Russian problem with the INF Treaty was that China was not bound by it and continued to build up their own intermediate-range forces.[61]

According to Russian officials and the American academic Theodore Postol, the US decision to deploy its missile defense system in Europe was a violation of the treaty as they claim they could be quickly retrofitted with offensive capabilities;[62][63][64] this accusation has in turn been rejected by US and NATO officials and academic Jeffrey Lewis.[64][65] Russian experts also stated that the US usage of target missiles and unmanned aerial vehicles, such as the MQ-9 Reaper and MQ-4 Triton, violated the INF Treaty,[66] which has also in turn been rejected by US officials.[67]

US withdrawal and termination

[edit]The US declared its intention to withdraw from the treaty on 20 October 2018, citing the previous violations of the treaty by Russia.[7][12][13] This prompted Putin to state that Russia would not launch first in a nuclear conflict but would "annihilate" any adversary, essentially re-stating the policy of "Mutually Assured Destruction". Putin claimed Russians killed in such a conflict "will go to heaven as martyrs".[68]

It was also reported that the US need to counter a Chinese arms buildup in the Pacific, including within South China Sea, was another reason for their move to withdraw, because China was not a signatory to the treaty.[7][12][13] US officials extending back to the presidency of Barack Obama have noted this. For example, Kelly Magsamen, who helped craft the Pentagon's Asian policy under the Obama administration, said China's ability to work outside of the INF treaty had vexed policymakers in Washington, long before Trump came into office.[69] A Politico article noted the different responses US officials gave to this issue: "either find ways to bring China into the treaty or develop new American weapons to counter it" or "negotiating a new treaty with that country".[70] The deployment since 2016 of the Chinese DF-26 IRBM with a range of 4,000 km (2,500 mi) meant that US forces as far as Guam can be threatened.[69] The United States Secretary of Defense at the time, Jim Mattis, was quoted stating that "the Chinese are stockpiling missiles because they're not bound by [the treaty] at all".[7] Bringing an ascendant China into the treaty, or into a new comprehensive treaty including other nuclear powers, was further complicated by complex relationships between China, India, and Pakistan.[71]

The Chinese Foreign Ministry said a unilateral US withdrawal would have a negative impact and urged the US to "think thrice before acting". On 23 October 2018, John R. Bolton, the US National Security Advisor, said on the Russian radio station Echo of Moscow that recent Chinese statements indicate that it wants Washington to stay in the treaty, while China itself is not bound by it.[69] On the same day, a report in Politico suggested that China was "the real target of the [pull out]".[70] It was estimated that 90% of China's ground missile arsenal would be outlawed if China were a party to the treaty.[70] Bolton said in an interview with Elena Chernenko from the Russian newspaper Kommersant on 22 October 2018: "we see China, Iran, North Korea all developing capabilities which would violate the treaty if they were parties to it."[72]

On 26 October 2018, Russia unsuccessfully called for a vote to get the United Nations General Assembly to consider calling on Washington and Moscow to preserve and strengthen the treaty.[73] Russia had proposed a draft resolution in the 193-member General Assembly's disarmament committee, but missed 18 October submission deadline[73] so it instead called for a vote on whether the committee should be allowed to consider the draft.[73] On the same day, Bolton said in an interview with Reuters that the INF Treaty was a Cold War relic and he wanted to hold strategic talks with Russia about Chinese missile capabilities.[74]

Four days later at a news conference in Norway, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg called on Russia to comply with the treaty saying "The problem is the deployment of new Russian missiles".[75] Putin announced on 20 November 2018 that the Kremlin was prepared to discuss the INF Treaty with Washington but would "retaliate" if the United States withdrew.[76]

Starting on 4 December 2018, the US asserted that Russia had 60 days to comply with the treaty.[77] On 5 December 2018, Russia responded by revealing their Peresvet combat laser, stating the weapon system had been deployed with the Russian Armed Forces as early as 2017 "as part of the state procurement program".[78]

Russia presented the 9M729 (SSC-8) missile and its technical parameters to foreign military attachés at a military briefing on 23 January 2019, held in what it said was an exercise in transparency it hoped would persuade Washington to stay in the treaty.[79] The Russian Defence Ministry said diplomats from the US, Britain, France and Germany had been invited to attend the static display of the missile, but they declined.[79] The US had previously rejected a Russian offer to do so because it said such an exercise would not allow the Americans to verify the true range of the missile.[79] A summit between the United States and Russia on 30 January 2019 failed to find a way to preserve the treaty.[80]

The US suspended its compliance with the INF Treaty on 2 February 2019 following an announcement by US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo the day prior. In a statement, Trump said there was a six-month timeline for full withdrawal and INF Treaty termination if the Russian Federation did not come back into compliance within that period.[81][71] The same day, Putin announced that Russia had also suspended the INF Treaty in a 'mirror response' to Trump's decision, effective that day.[citation needed] The next day, Russia started work on new intermediate range (ballistic) hypersonic missiles along with land-based 3M-54 Kalibr systems (both nuclear capable) in response to the US announcing it would start to conduct research and development of weapons formerly prohibited under the treaty.[82]

Following the six-month US suspension of the INF Treaty, the Trump administration formally announced it had withdrawn from the treaty on 2 August 2019. On that day, Pompeo stated that "Russia is solely responsible for the treaty's demise".[83] While formally ratifying a treaty requires the support of two-thirds of the members of the US Senate, because Congress has rarely acted to stop a number of presidential decisions regarding international treaties during the 20th and 21st centuries, there have been established a precedent that the president and executive branch can unilaterally withdraw from a treaty without congressional approval.[84] On the day of the withdrawal, the US Department of Defense announced plans to test a new type of missile that would have violated the treaty, from an eastern NATO base. Military leaders stated the need for this new missile to stay ahead of both Russia and China, in response to Russia's continued violations of the treaty.[83]

The US withdrawal was backed by most of its NATO allies, citing years of Russian non-compliance with the treaty.[83] In response to the withdrawal, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov invited the US and NATO "to assess the possibility of declaring the same moratorium on deploying intermediate-range and shorter-range equipment as we have, the same moratorium Vladimir Putin declared, saying that Russia will refrain from deploying these systems when we acquire them unless the American equipment is deployed in certain regions."[83] This moratorium request was rejected by NATO's Stoltenberg who said that it was not credible as Moscow had already deployed such warheads.[85] On 5 August 2019, Putin stated, "As of August 2, 2019, the INF Treaty no longer exists. Our US colleagues sent it to the archives, making it a thing of the past."[86]

On 18 August 2019, the US conducted a test firing of a missile that would not have been allowed under the treaty; a ground-based version of the Tomahawk, similar to the BGM-109G banned by the treaty decades prior.[87][88][89] The Pentagon said that the data collected and lessons learned from this test would inform its future development of intermediate-range capabilities, while the Russian foreign ministry said that it was a cause for regret, and accused the United States of escalating military tensions.[87][88][89]

Further reactions to the withdrawal

[edit]Numerous prominent nuclear arms control experts, including George Shultz, Richard Lugar and Sam Nunn, urged Trump to preserve the treaty.[90] Gorbachev criticized Trump's nuclear treaty withdrawal as "not the work of a great mind" and stated "a new arms race has been announced".[91][92] The decision was criticized by the chairmen of the House Committees on Foreign Affairs and Armed Services Eliot Engel and Adam Smith, who said that instead of crafting a plan to hold Russia accountable and pressure it into compliance, the Trump administration had offered Putin an easy way out of the treaty and played right into his hands.[93] Similar arguments had been brought previously on 25 October 2018 by European members of NATO who urged the US "to try to bring Russia back into compliance with the treaty rather than quit it, seeking to avoid a split in the alliance that Moscow could exploit".[73]

NATO chief Stoltenberg suggested the INF Treaty could be expanded to include countries such as China and India, an idea that both the US and Russia had indicated being open to, although Russia had expressed skepticism that such an expansion could be achieved.[94]

There were contrasting opinions on the withdrawal among American lawmakers. The INF Treaty Compliance Act (H.R. 1249) was introduced to stop the United States from using Government funds to develop missiles prohibited by the treaty,[95][96] while Republican senators Jim Inhofe and Jim Risch issued statements of support for the withdrawal.[97]

On 8 March 2019, the Foreign Ministry of Ukraine announced that since the United States and Russia had both pulled out of the treaty, it now had the right to develop intermediate-range missiles, citing Russian aggression against Ukraine as a serious threat to the European continent, and the presence of Russian Iskander-M nuclear-capable missile systems in Russian-annexed Crimea.[98] Ukraine was home to about forty percent of the Soviet space industry, but was never allowed to develop a missile with the range to strike Moscow,[citation needed] only having both longer and shorter-ranged missiles, but it has the capability to develop intermediate-range missiles.[99]

After the United States withdrew from the treaty, some American commentators wrote that this might allow the country to more effectively counter Russia and China's missile forces.[100][101][102] This was later followed by the development and deployment of the Typhon Medium Range Capability weapon system in 2023.

According to Brazilian journalist Augusto Dall'Agnol, the INF Treaty's demise also needs to be understood in the broader context of the gradual erosion of the strategic arms control regime that started with the US withdrawal from the ABM Treaty in 2002 amidst Russia's objections.[103][opinion]

New medium range missiles in Europe

[edit]In late-2023 and early-2024, Russia used North Korean Hwasong-11A and/or Hwasong-11B missiles in the Russo-Ukrainian War.[104]

In June 2024, Russian President Putin called for resuming production of medium-range missiles.[105][106]

Starting from 2026, Typhon missile launcher with SM-6, Tomahawk and longer range hypersonic weapons of the United States will be deployed to Germany. This marks the return of the Tomahawk cruise missile to German territory.[107][108]

At the 2024 NATO summit, Poland, Germany, France and Italy signed a memorandum of understanding to jointly develop ground-launched cruise missiles with a range of more than 500 kilometres.[109]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Formally the Treaty Between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on the Elimination of Their Intermediate-Range and Shorter-Range Missiles

- ^ Russian: Договор о ликвидации ракет средней и меньшей дальности / ДРСМД; Dogovor o likvidatsiy raket sredney i menshey dalnosti / DRSMD

References

[edit]- ^ a b Garthoff, Raymond L. (1994). The Great Transition: American-Soviet Relations and the End of the Cold War. Brookings Institution. p. 326. ISBN 978-0-8157-3060-6.

The reason for this precision of timing… was a mystery to almost everyone in both governments… Only much later did it become known that the time had been selected as propitious by Nancy Reagan's astrologer

- ^ a b c d "Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF Treaty)". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ AP Archive (21 July 2015). "Reagan And Gorbachev Meet, Reagan And Gorbachev Sign Ratification Instruments For INF Treaty". Archived from the original on 12 December 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ "INF Treaty". United States Department of State. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ Kramer, Andrew E.; Specia, Megan (1 February 2019). "What Is the I.N.F. Treaty and Why Does It Matter?". The New York Times.

- ^ Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (2007). SIPRI Yearbook 2007: Armaments, Disarmament, and International Security. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 683. ISBN 978-0-19-923021-1.

- ^ a b c d e Sanger, David E.; Broad, William J. (19 October 2019). "U.S. to Tell Russia It Is Leaving Landmark I.N.F. Treaty". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ Pengelly, Martin (20 October 2018). "Trump says US will withdraw from nuclear arms treaty with Russia". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ "What the INF Treaty's Collapse Means for Nuclear Proliferation". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ "9M729 (SSC-8)". Missile Threat. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ Borger, Julian (2 October 2018). "US Nato envoy's threat to Russia: stop developing missile or we'll 'take it out'". Guardian News & Media Limited.

- ^ a b c "President Trump to pull US from Russia missile treaty". BBC. 20 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ a b c "Trump: U.S. to exit nuclear treaty, citing Russian violations". Reuters. 20 October 2019.

- ^ "Pompeo announces suspension of nuclear arms treaty". CNN. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty at a Glance, Arms Control Association, August 2019.

- ^ a b c "INF nuclear treaty: US pulls out of Cold War-era pact with Russia". BBC News. 2 August 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ Cant, James (May 1998). "The development of the SS-20" (PDF). Glasgow Thesis Service. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ "RSD-10 MOD 1/-MOD 2 (SS-20)". Missile Threat. 17 October 2012. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ a b c "Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces [INF] Chronology". Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ a b c Bohlen et al. 2012, p. 7.

- ^ Bohlen et al. 2012, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b c d e f "Paul Nitze and A Walk in the Woods – A Failed Attempt at Arms Control". Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. 30 March 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ^ a b "Interview with Leslie H. Gelb". National Security Archive. 28 February 1999. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ^ Legge 1983, p. 1.

- ^ "Soviet Long Range Theater Nuclear Forces" (PDF). CIA.gov. 6 April 1978. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 January 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ "Special Meeting of Foreign and Defence Ministers (The "Double-Track" Decision on Theatre Nuclear Forces)". NATO. 12 December 1979. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ Legge 1983, pp. 1–2, 35–37.

- ^ Bohlen et al. 2012, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Bohlen et al. 2012, pp. 6, 9.

- ^ Burr, William; Wampler, Robert (27 October 2004). ""The Master of the Game": Paul H. Nitze and U.S. Cold War Strategy from Truman to Reagan". National Security Archive. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ^ a b c d Bohlen et al. 2012, p. 9.

- ^ "Yuli A. Kvitsinsky: Chief Soviet arms control negotiator". United Press International. 25 September 1981. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ^ Freudenheim, Milt; Slavin, Barbara (6 December 1981). "The World in Summary; Arms Negotiators in Geneva Begin To Chip the Ice". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ^ a b Wittner, Lawrence S. (1 April 2000). "Reagan and Nuclear Disarmament". Boston Review. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- ^ "Nomination of William F. Burns To Be Director of the United States Arms Control and Disarmament Agency". Ronald Reagan Presidential Library. 7 January 1988. Archived from the original on 21 September 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ^ a b Bohlen et al. 2012, pp. 9–10.

- ^ a b Berger, Marilyn (21 October 2004). "Paul H. Nitze, Missile Treaty Negotiator and Cold War Strategist, Dies at 97". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ^ a b c d Nitze, Paul (20 October 1990). "Paul Nitze Interview" (Interview). Interviewed by Academy of Achievement. Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ^ Bohlen et al. 2012, p. 10.

- ^ Charles Moore, Margaret Thatcher: At Her Zenith (2016) 2: 23–26, 594–5.

- ^ Charles Moore, Margaret Thatcher: At Her Zenith (2016) 2: 590–96.

- ^ Carr, William (1991). A History of Germany: 1815–1990 (4th ed.). London, United Kingdom: Harold & Stoughton. p. 393.

- ^ CQ Press (2012). Guide to Congress. SAGE. pp. 252–53. ISBN 978-1-4522-3532-5.

- ^ "Senate Votes 93-5 to Approve Ratification of the INF Treaty", CQ Weekly Report 42#22 (1988): 1431–35.

- ^ a b c "Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF Treaty)". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ Trakimavicius, Lukas (15 May 2018). "Why Europe needs to support the US-Russia INF Treaty". EurActiv. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF Treaty)". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Adherence to and the Compliance with Arms Control, Nonproliferation, and Disarmament Agreements and Commitments" (PDF). U.S. Department of State. July 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ Mendelsohn, Jack (April 1991). "Why START?". Arms Control Today. 21 (3): 3–9. JSTOR 23624481.

- ^ a b Bohlen et al. 2012.

- ^ "Putin rails against US foreign policy". Financial Times. 10 February 2007. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ "Россия "может выйти" из договора с США о ракетах". BBC. 15 February 2007. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012.

- ^ a b Gordon, Michael R. (14 February 2017). "Russia Deploys Missile, Violating Treaty and Challenging Trump". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ^ Norris, Cochran; et al. (1989), SIPRI Yearbook 1989: World Armaments and Disarmament (PDF), p. 21, archived from the original (PDF) on 9 December 2008, retrieved 4 February 2009

- ^ Rogin, Josh (7 December 2013). "US Reluctant to Disclose to All NATO Allies that Russia is Violating INF Treaty". The Atlantic Council. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- ^ Marcus, Jonathan (30 January 2014). "US briefs Nato on Russian 'nuclear treaty breach'". BBC News. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ Luhn, Alec; Borger, Julian (29 July 2014). "Moscow may walk out of nuclear treaty after US accusations of breach". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ Woolf, Amy F. (27 January 2017). "Russian Compliance with the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty: Background and Issues for Congress". Congressional Research Service (7–5700). Archived from the original on 18 June 2017.

- ^ "Statement on the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty". NATO. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ^ "Nato accuses Russia of breaking nuclear missile treaty". BBC. 4 December 2018.

- ^ Mark Stokes and Dan Blumenthal "Can a treaty contain China's missiles?" Washington Post, 2 January 2011.

- ^ "Russia may have violated the INF Treaty. Here's how the United States appears to have done the same". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 7 February 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

The Western press has often treated the Russian claim that US missile defense installations have an offensive capability as rhetorical obfuscation. But publicly available information makes it clear that the US Aegis-based systems in Eastern Europe, if equipped with cruise missiles, would indeed violate the INF.

- ^ Kennedy, Kristian (12 July 2018). "Destabilizing Missile Politics Return to Europe, Part II: For Russia, Pershing II Redux?". NAOC.

- ^ a b Gotev, Georgi. "Moscow: US comments on possible destruction of Russian warheads are dangerous". euractiv.

- ^ Majumdar, Dave (14 February 2017). "Russia's Dangerous Nuclear Forces are Back". National Review.

The Russians will inevitably claim that the United States violated the INF treaty first with Aegis Ashore missile defense sites, which use the Mk-41 vertical launch system. The Mk-41 is capable of launching the Tomahawk cruise missile—which could be argued is a violation of the treaty. "As for the Mk 41, it's kind of a [flimsy] argument," Lewis said. "The Mk-41 is a launcher, right? So... The treaty prohibits 'GLCM launchers' and 'GLBM launchers.' The Tomahawk is permitted because it is a SLCM. Moving the MK41 to land would be a problem if we then fired a Tomahawk off it. But we've only fired SAMs out of it and the treaty contains an exception for SAMs. Then the Tomahawk would be a GLCM. But it's not." The United States has offered to allow Moscow to inspect the Mk-41 sites to verify that they do not contain Tomahawks, however, the Russians have refused. "As a practical matter, the U.S. should—and in fact has—offered to let the Russians take a look and reassure themselves," Lewis said. "Russians refused."

- ^ Adomanis, Mark (31 July 2014). "Russian Nuclear Treaty Violation: The Basics". U.S. Naval Institute. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ Herteleer, Simon (11 February 2019). "Analysis: The INF Treaty". ATA. Archived from the original on 7 August 2019.

Russia furthermore claims that the use of unmanned aerial vehicles, such as the MQ-9 Reaper and the MQ-4 violate the INF treaty, something the United States vehemently denies.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "'Aggressors Will Be Annihilated, We Will Go to Heaven as Martyrs,' Putin Says". The Moscow Times. Russia. 19 October 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ a b c "Trump's missile treaty pullout could escalate tension with China". reuters. 23 October 2018.

- ^ a b c Hellman, Gregory (23 October 2018). "Chinese missile buildup strained US-Russia arms pact". Politico.eu. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ a b Sanger, David E.; Broad, William J. (1 February 2019). "U.S. Suspends Nuclear Arms Control Treaty With Russia". The New York Times – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ "APNSA John Bolton Interview with Elena Chernenko, Kommersant – Moscow, Russia – October 22, 2018". www.ru.usembassy.gov. U.S. Embassy & Consulates in Russia. 22 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Russia, U.S. Clash over INF arms treaty at United Nations". Reuters. 26 October 2018.

- ^ "Trump adviser says wants U.S.-Russia strategic talks on Chinese threat". Reuters. 26 October 2018.

- ^ "NATO's Stoltenberg calls on Russia to comply with INF nuclear treaty". Reuters.

- ^ "Putin Says Russia Will Retaliate if U.S. Quits INF Nuclear Missile Treaty". 20 November 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ^ "U.S., NATO give Russia 60 days to comply with nuclear pact". NBC News. 4 December 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ "Peresvet combat lasers enter duty with Russia's armed forces". TASS. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ^ a b c Balmforth & Osborn, Tom & andrew (23 January 2019). "Russia takes wraps off new missile to try to save U.S. nuclear pact". Reuters. Reuters.

- ^ Washington (earlier), Gabrielle Canon Ben Jacobs in; Holden, Emily (1 February 2019). "Trump picks climate change skeptic for EPA science board – latest news" – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ Ho, Vivian; Gabbatt, Adam; Durkin, Erin (1 February 2019). "Roger Stone case: judge 'considering gag order' against Trump adviser – live". The Guardian – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ "Putin threatens new arms race after Trump pulls US out of nuclear weapons treaty". The Independent. 2 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d Stracqualursi, Veronica; Gaouette, Nicole; Starr, Barbara; Atwood, Kylie (2 August 2019). "US formally withdraws from nuclear treaty with Russia and prepares to test new missile". CNN. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ Feingold, Russell (7 May 2018). "Donald Trump can unilaterally withdraw from treaties because Congress abdicated responsibility". NBC News. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ "Russian request for missile freeze has 'zero credibility': Stoltenberg". Reuters. 2 August 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- ^ "Statement by the President of Russia on the unilateral withdrawal of the United States from the Treaty on the Elimination of Intermediate-Range and Shorter-Range Missiles". en.kremlin.ru. 5 August 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- ^ a b Ryan, Missy (20 August 2019). "US tests its first intermediate-range missile since quitting treaty with Russia". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ a b "INF nuclear treaty: US tests medium-range cruise missile". BBC News. 20 August 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ a b "The US proves Russia right with its first post-treaty missile launch". QZ. 21 August 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ Gladstone, Rick (8 November 2018). "In Bipartisan Pleas, Experts Urge Trump to Save Nuclear Treaty With Russia". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ Ellyatt, Holly (22 October 2018). "Gorbachev says Trump's nuclear treaty withdrawal 'not the work of a great mind'". CNBC.

- ^ Swanson, Ian (27 October 2018). "Trump stokes debate about new Cold War arms race". The Hill.

- ^ Eliot Engel and Adam Smith (2 February 2019). "US pulling out of the INF treaty rewards Putin, hurts NATO". CNN.

- ^ "NATO chief Stoltenberg bats for expanded INF treaty deal with more members | DW | 07.02.2019". DW.COM. Deutsche Welle.

- ^ Blake, Andrew (15 February 2019). "Bill offered to keep U.S. in compliance with collapsing Cold War-era weapons treaty". AP News. The Washington Times. Archived from the original on 25 February 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ "Text - H.R.1249 - 116th Congress (2019-2020): INF Treaty Compliance Act of 2019 | Congress.gov | Library of Congress".

- ^ Brown, David (2 August 2019). "U.S. officially pulls out of missile treaty with Russia today". Politico.

- ^ Maza, Cristina (8 March 2019). "Ukraine has the right to develop missiles now that Russia-U.S. nuclear treaty is canceled, Kiev says". Newsweek. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ Budjeryn, Mariana; Steiner, Steven E. (4 March 2019). "Forgotten Parties to the INF". Wilson Center. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ Williams, Clive (31 January 2019). "Pacific collateral from the INF Treaty collapse". Lowy Institute. The Interpreter.

- ^ Mahnken, Thomas G (16 July 2019). "Countering Missiles With Missiles: U.S. Military Posture After the INF Treaty". War on the rocks.

- ^ Walton, Timothy A (5 August 2019). "America Could Lose a Real War Against Russia". The New York Times.

- ^ Dall'Agnol, Augusto C.; Cepik, Marco (18 June 2021). "The demise of the INF Treaty: a path dependence analysis". Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional. 64 (2): 1–19. doi:10.1590/0034-7329202100202. ISSN 1983-3121. S2CID 237962045.

- ^ Gwadera, Zuzanna; Wright, Timothy (17 June 2024). "Missile transfers to Ukraine and wider NATO targeting dilemmas". International Institute for Strategic Studies. Retrieved 2 September 2024.

- ^ "Putin calls for new production of intermediate-range missiles". 29 June 2024.

- ^ "Will Russia deploy offensive missiles capable of striking Europe?".

- ^ Nechepurenko, Ivan; Sonne, Paul (11 July 2024). "Russia Vows 'Military Response' to U.S. Missile Deployments in Germany". The New York Times.

- ^ "The return of long-range US missiles to Europe".

- ^ "Four EU countries agree to co-develop long-range cruise missiles". 12 July 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bohlen, Avis; Burns, William; Pifer, Steven; Woodworth, John (2012). The Treaty on Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces: History and Lessons Learned (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- Davis E., Lynn (1988). "Lessons of the INF Treaty". Foreign Affairs. 66 (4): 720–734. doi:10.2307/20043479. ISSN 0015-7120. JSTOR 20043479.

- Garthoff, Raymond L. (1983). "The NATO Decision on Theater Nuclear Forces". Political Science Quarterly. 98 (2): 197–214. doi:10.2307/2149415. JSTOR 2149415.

- Gassert, Philip (2020). The INF Treaty of 1987: A Reappraisal. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Giles, Keir; Monaghan, Andrew (2014). European Missile Defense and Russia. Carlisle Barracks, PA: United States Army War College Press. ISBN 978-1-58487-635-9. Archived from the original on 12 February 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- Haass, Richard (1988). Beyond the INF Treaty: Arms, Arms Control, and the Atlantic Alliance. Lanham, MD: University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-8191-6942-6.

- Legge, J. Michael (1983). Theater Nuclear Weapons and the NATO Strategy of Flexible Response (PDF) (Report). RAND Corporation. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- Moniz & Nunn, Ernest & Sam (2019). "The Return of Doomsday: The New Nuclear Arms Race – and How Washington and Moscow Can Stop It". Foreign Affairs. 98 (5): 150–61.

- Rhodes, Richard (2008). Arsenals of Folly: The Making of the Nuclear Arms Race. New York, NY: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-375-71394-1.

- Ritter, Scott (2022). Disarmament in the Time of Perestroika: Arms Control and the End of the Soviet Union. Atlanta: Clarity Press. ISBN 978-1-949762-61-7.

- Woolf, Amy F. (25 April 2018). Russian Compliance with the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty: Background and Issues for Congress (PDF). Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

External links

[edit]- 1987 in the Soviet Union

- Arms control treaties

- Cold War treaties

- December 1987 events

- Military history of Russia

- Military history of the Soviet Union

- Military history of the United States

- 1987 in the United States

- Mikhail Gorbachev

- Nuclear technology treaties

- Nuclear weapons policy

- Nuclear weapons governance

- Perestroika

- Presidency of Ronald Reagan

- Soviet Union–United States treaties

- Russia–United States relations

- Russia–United States military relations

- Treaties of Belarus

- Treaties of Kazakhstan

- Treaties of Turkmenistan

- Treaties of Ukraine

- Treaties of Uzbekistan

- Treaties concluded in 1987

- Treaties entered into force in 1988