Hexi Corridor

| Hexi Corridor | |

|---|---|

| Gansu Corridor | |

Hexi Corridor at the Qilian Mountains Map of the Hexi Corridor | |

| Length | 1,000 km (620 mi) |

| Width | 50 km (31 mi) |

| Geography | |

| Location | Gansu Province, China |

| Population centers | Dunhuang, Yumen City, Jiayuguan City, Jiuquan, Zhangye, Jinchang, Wuwei, and Lanzhou |

| Borders on | Gobi Desert (north) Lanzhou (east) Qilian Mountains (south) Dunhuang (west) |

The Hexi Corridor (/həˈʃiː/ hə-SHEE),[a] also known as the Gansu Corridor, is an important historical region located in the modern western Gansu province of China. It refers to a narrow stretch of traversable and relatively arable plain west of the Yellow River's Ordos Loop (hence the name Hexi, meaning 'west of the river'), flanked between the much more elevated and inhospitable terrains of the Mongolian and Tibetan Plateaus.

As part of the Northern Silk Road, running northwest from the western section of the Ordos Loop between Yinchuan and Lanzhou, the Hexi Corridor was the most important trade route in Northwest China. It linked China proper to the historic Western Regions for traders and military incursions into Central Asia. It is a string of oases along the northern edges of the Qilian Mountains and Altyn-Tagh, with the high and desolate Tibetan Plateau further to the south. To the north are the Longshou, Heli and Mazong Mountains separating it from the arid Badain Jaran Desert, Gobi Desert and the cold steppes of the Mongolian Plateau. At the western end, the route splits into three, going either north of the Tianshan Mountains or south on either side of the Tarim Basin. At the eastern end, the mountains around Lanzhou grants access to the Longxi Basin, which leads east through Mount Long along the Wei River valley into the populous Guanzhong Plain, and then into the Central Plain.

Geography

[edit]Location

[edit]The Hexi Corridor is located in western Gansu province, bordered to the south by the Qilian Mountains and to the north by the Gobi Desert. It extends for approximately 1,000–1,200 kilometres (620–750 mi) from Wushao Mountain in the south to Dunhuang in the north, and covers approximately 5,100 square kilometres (2,000 sq mi).[1][2][3]

There are several major cities along the Hexi Corridor. From west to east, the major cities are: Dunhuang, Yumen, Jiayuguan, Jiuquan, Zhangye, Jinchang, Wuwei, and finally Lanzhou in the southeast.[4][5] Just south of the provincial boundary of Gansu lies Xining, the capital of Qinghai Province, which served as the chief commercial hub of the Hexi Corridor along the Northern Silk Road.[6]

History

[edit]Prehistory

[edit]The Hexi Corridor was first settled around 4800 BP by Chinese millet farmers from the Yangshao Culture in the western Loess Plateau,[7][8][9] who enabled the transfer of millet to Central Asia, and consequently to the rest of Eurasia and Africa.[10] Wheat and barley from the Fertile Crescent arrived in the Hexi Corridor via Central Asia around 4000 BP,[8][10][11] and later spread into China proper.[12] By 3700 BP, most likely due to the weakening and retreat of the East Asian monsoon in the area, the more drought-resistant wheat and barley had replaced millet as the main staple crop in the Hexi Corridor.[7][13][14] Several Neolithic cultures developed in the Hexi corridor at this time, such as the Majiayao, Banshan, and Machang.[8]

The oldest bronze object to be discovered in China, dating to around 5000-4500 BP, was found at a Majiayao site in the Hexi Corridor,[15] and the Bronze Age began in the Hexi Corridor around 4200 BP with the arrival of bronze-smelting technology.[14] Domesticated livestock were also introduced to the area around this time,[16] so Bronze Age cultures of the Hexi Corridor typically farmed millet and wheat, while keeping livestock such as sheep, pigs, cattle and horses as well as producing bronze objects.[14] Bronze age societies in the Hexi Corridor at this time include the Qijia, Xichengyi, Siba, Shajing, and Shanma cultures.[8]

The Hexi Corridor underwent further aridification around 3500 BP during the Iron Age, and cultures at the time (such as the Shajing culture) saw a decrease in their number of settlements, becoming dominated by nomadic production rather than agriculture.[17][18][19]

Qin dynasty

[edit]At the end of the Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE), the Yuezhi overcame previous settlers, the Wusun and Qiang, occupying the western Hexi Corridor.[20] All three were possibly connected with the Shajing, and the Wusun were possibly associated with the Shanma culture.[21][22] Later, the newly risen Xiongnu armies under Modu Chanyu vanquished and expelled the Yuezhi, and established a dominant confederacy empire during the Chu-Han contention and the early Han dynasty.[20]

Han dynasty

[edit]

Protectorate of the Western Regions (Tarim Basin)

During the reign of Emperor Wen of Han, Modu's son Laoshang Chanyu defeated Yuezhi again in 162 BCE, forcing the westward exodus of majority of the Yuezhi survivors (later known as the Greater Yuezhi) into Central Asia, while the small portion of Yuezhi population that didn't migrate (known as the Lesser Yuezhi) was forced to mixed among the Qiang people and become the subjects of Xiongnu's Worthy Prince of the Right. At this point, the Hexi Corridor was under complete Xiongnu control, mainly occupied by the two tribes of Hunye and Xiutu.

In 138 BCE, Emperor Wu sent Zhang Qian as the ambassador to the Western Regions in an attempt to make contact with Greater Yuezhi. Zhang Qian's envoy was intercepted by Xiongnu while travelling through the Hexi Corridor, and he was held a captive for ten years, until he finally escaped and continued his mission further west. He eventually arrived at Yuezhi territory, but was unable to convince the Yuezhi leaders to ally against Xiongnu. On his return journey he was once again captured by Xiongnu while traversing the Hexi Corridor, but again managed to escape two years later. He finally returned to Chang'an in 125 BCE, bringing back invaluable detailed information about the various Central Asian kingdoms such as Dayuan, Daxia and Kangju, as well as other farther countries such as Anxi, Tiaozhi, Shendu and Wusun.

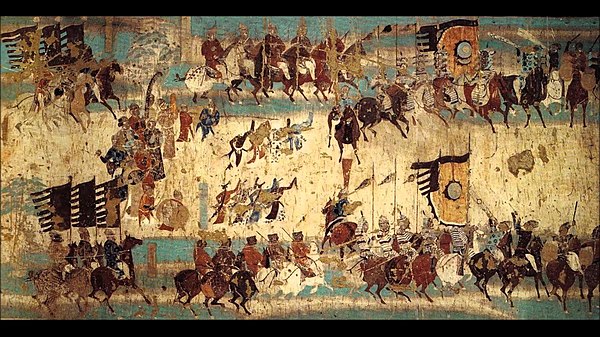

During the Han–Xiongnu War, Han general Huo Qubing expelled the Xiongnu from the Hexi Corridor and even drove them from Lop Nur when King Hunye surrendered to Huo Qubing in 121 BCE. The Han Empire acquired a new territory with trade access to the Western Regions, and also cutting the Xiongnu off from their Qiang allies. Again in 111 BCE, Han forces repelled a joint Xiongnu-Qiang invasion, and to consolidate the control of the region, four new commanderies were established in the Hexi Corridor, namely (from east to west) Wuwei, Zhangye, Jiuquan and Dunhuang, collectively known as the Four Commanderies of Hexi (Chinese: 河西四郡).

From roughly 115–60 BCE, Han forces fought the Xiongnu over control of the oasis city-states in the Tarim Basin. Han was eventually victorious and established the Protectorate of the Western Regions in 60 BCE, which dealt with the region's defense and foreign affairs.

During the turbulent reign of Wang Mang, Han lost control over the Tarim Basin, which was reconquered by the Xiongnu in 63 CE and used as a base to invade the Hexi Corridor. Dou Gu defeated the Xiongnu again at the Battle of Yiwulu in 73 CE, evicting them from Turpan and chasing them as far as Lake Barkol before establishing a garrison at Hami.

After the new Protector General of the Western Regions Chen Mu was killed in 75 CE by allies of the Xiongnu in Karasahr and Kucha, the garrison at Hami was withdrawn. At the Battle of the Altai Mountains in 89 CE, Dou Xian defeated the Northern Chanyu, who retreated into the Altai Mountains. The Han forces, allied with the subjugated Southern Xiongnu, again defeated the Northern Chanyu twice in 90 CE and 91 CE, forcing him to flee west into Wusun and Kangju territories.

Tang dynasty

[edit]

The Tang dynasty fought the Tibetan Empire for control of areas in Inner and Central Asia. There was a long string of conflicts with Tibet over territories in the Tarim Basin between 670 and 692.

In 763 the Tibetans even captured the Tang capital of Chang'an for fifteen days during the An Lushan Rebellion. It was during this rebellion that the Tang withdrew its western garrisons stationed in what is now Gansu and Qinghai, which the Tibetans then occupied along with the area that is modern Xinjiang. Hostilities between the Tang and Tibet continued until they signed a formal peace treaty in 821. The terms of this treaty, including fixed borders between the two countries, are recorded in a bilingual inscription on a stone pillar outside the Jokhang in Lhasa.

Western Xia dynasty

[edit]The Western Xia dynasty was established in the 11th century by the Tangut people. Western Xia controlled from 1038 CE up to 1227 CE the areas in what are now the northwestern Chinese provinces of Gansu, Shaanxi, and Ningxia.

Yuan dynasty

[edit]Genghis Khan began the conquest of the Jin dynasty around 1207 and Ögedei Khan continued it after his death in 1227. The Jurchen-led Jin dynasty fell in 1234 CE with help from the Han-ruled Southern Song dynasty.

Ögedei also conquered the Western Xia dynasty in 1227, pacifying the Hexi Corridor region, which was later absorbed into the Yuan dynasty.

Geography and climate

[edit]The Hexi Corridor is a long, narrow passage stretching for some 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) from the steep Wushaolin hillside near the modern city of Lanzhou to the Jade Gate[24] at the border of Gansu and Xinjiang. There are many fertile oases along the path, watered by rivers flowing from the Qilian Mountains, such as the Shiyang, Jinchuan, Ejin (Heihe), and Shule Rivers.

A strikingly inhospitable environment surrounds this chain of oases: the snow-capped Qilian Mountains (the so-called "southern mountains" or "Nanshan") to the south; the Beishan ("northern mountains") mountainous area, the Alashan Plateau, and the vast expanse of the Gobi desert to the north.

Geologically, the Hexi Corridor belongs to a Cenozoic foreland basin system on the northeast margin of the Tibetan Plateau.[25]

The ancient trackway formerly passed through Haidong, Xining and the environs of Juyan Lake, serving an effective area of about 215,000 km2 (83,000 sq mi). It was an area where mountain and desert limited caravan traffic to a narrow trackway, where relatively small fortifications could control passing traffic.[26]

There are several major cities along the Hexi Corridor. In western Gansu Province is Dunhuang (Shazhou), then Yumen, then Jiayuguan, then Jiuquan (Suzhou), then Zhangye (Ganzhou) in the center, then Jinchang, then Wuwei (Liangzhou) and finally Lanzhou in the southeast. In the past, Dunhuang was part of the area known as the Western Regions. South of Gansu Province, in the middle just over the provincial boundary, lies the city of Xining, the capital of Qinghai Province. Xining used to be the chief commercial hub of the Hexi Corridor.

The Jiayuguan fort guards the western entrance to China. It is located in Jiayuguan pass at the narrowest point of the Hexi Corridor, some 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) southwest of the city of Jiayuguan. The Jiayuguan fort is the first fortification of Great Wall of China in the west.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Chinese: 河西走廊; pinyin: Héxī Zǒuláng; Wade–Giles: Ho2-hsi1 Tsou3-lang2; Dungan: Хәщи зулон; Xiao'erjing: حْسِ ظِوْلاْ; Mandarin pronunciation: [xɤ̌ɕí tsòʊlɑ̌ŋ]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Zhihong Wang, Dust in the Wind: Retracing Dharma Master Xuanzang's Western Pilgrimage, 經典雜誌編著, 2006 ISBN 9868141982

- ^ Clydesdale, Heather (23 June 2018). "Rethinking China's Frontier: Archaeological Finds Show the Hexi Corridor's Rapid Emergence as a Regional Power". Humanities. 7 (3): 63. doi:10.3390/h7030063. ISSN 2076-0787.

- ^ Zhu, Bing-Qi; Zhang, Jia-Xing; Sun, Chun (2021-08-17). "Physiochemical Characteristics, Provenance, and Dynamics of Sand Dunes in the Arid Hexi Corridor". Frontiers in Earth Science. 9: 726. Bibcode:2021FrEaS...9..726Z. doi:10.3389/feart.2021.728202. ISSN 2296-6463.

- ^ "Silk Road History of Hexi Corridor-China Silk Road Travel". www.china-silkroad-travel.com. Retrieved 2024-11-13.

- ^ "Google Maps". Google Maps. Retrieved 2024-11-13.

- ^ "Xining - Xining Travel Guide, Map, History, Attractions, Transportation". www.silkroadtourcn.com. Retrieved 2024-11-13.

- ^ a b Dong, Guanghui; Liang, Huan; Zhang, Zhixiong (2024-09-01). "Human–environment interaction along the eastern Silk Road during the Neolithic and Bronze Age". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 649: 112340. Bibcode:2024PPP...64912340D. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2024.112340. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ a b c d Dong, Guanghui; Yang, Yishi; Liu, Xinyi; Li, Haiming; Cui, Yifu; Wang, Hui; Chen, Guoke; Dodson, John; Chen, Fahu (17 October 2017). "Prehistoric trans-continental cultural exchange in the Hexi Corridor, northwest China". The Holocene. 28 (4): 621–628. doi:10.1177/0959683617735585. ISSN 0959-6836.

- ^ Li, Yu; Gao, Mingjun; Zhang, Zhansen; Duan, Junjie; Xue, Yaxin (2023-04-01). "Phased human-nature interactions for the past 10 000 years in the Hexi Corridor, China". Environmental Research Letters. 18 (4): 044035. Bibcode:2023ERL....18d4035L. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/acc87b. ISSN 1748-9326.

- ^ a b Stevens, C. J.; Murphy, C.; Roberts, R.; Lucas, L.; Silva, F.; Fuller, D. Q. (2016). "Between China and South Asia: A Middle Asian corridor of crop dispersal and agricultural innovation in the Bronze Age". The Holocene. 26 (10): 1541–1555. Bibcode:2016Holoc..26.1541S. doi:10.1177/0959683616650268. ISSN 0959-6836. PMC 5125436. PMID 27942165.

- ^ Li, Haiming; James, Nathaniel; Chen, Junwei; Zhang, Shanjia; Du, Linyao; Yang, Yishi; Chen, Guoke; Ma, Minmin; Jia, Xin (6 February 2023). "Agricultural Economic Transformations and Their Impacting Factors around 4000 BP in the Hexi Corridor, Northwest China". Land. 12 (2): 425. doi:10.3390/land12020425. ISSN 2073-445X.

- ^ Li, Xiaoqiang; Dodson, John; Zhou, Xinying; Zhang, Hongbin; Masutomoto, Ryo (5 January 2007). "Early cultivated wheat and broadening of agriculture in Neolithic China". The Holocene. 17 (5): 555–560. Bibcode:2007Holoc..17..555L. doi:10.1177/0959683607078978. ISSN 0959-6836.

- ^ Yang, Liu; Shi, Zhilin; Zhang, Shanjia; Lee, Harry F. (5 June 2020). "Climate Change, Geopolitics, and Human Settlements in the Hexi Corridor over the Last 5,000 Years". Acta Geologica Sinica - English Edition. 94 (3): 612–623. Bibcode:2020AcGlS..94..612Y. doi:10.1111/1755-6724.14529. ISSN 1000-9515.

- ^ a b c Xinying, Zhou; Xiaoqiang, Li; Dodson, John; Keliang, Zhao; Atahan, Pia; Nan, Sun; Qing, Yang (2012-03-16). "Land degradation during the Bronze Age in Hexi Corridor (Gansu, China)". Quaternary International. Holocene Vegetation Dynamics and Human Impact: Agricultural Activities and Rice Cultivation in East Asia II. 254: 42–48. Bibcode:2012QuInt.254...42X. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2011.06.046. ISSN 1040-6182.

- ^ Chen, G.; Cui, Y.; Liu, R.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Pollard, A. M.; Li, Y. (4 April 2020). "Lead isotopic analyses of copper ores in the Early Bronze Age central Hexi Corridor, north-west China". Archaeometry. 62 (5): 952–964. doi:10.1111/arcm.12566. hdl:21.11116/0000-0006-0FF7-4. ISSN 0003-813X.

- ^ Ren, Lele; Yang, Yishi; Qiu, Menghan; Brunson, Katherine; Chen, Guoke; Dong, Guanghui (2022-08-01). "Direct dating of the earliest domesticated cattle and caprines in northwestern China reveals the history of pastoralism in the Gansu-Qinghai region". Journal of Archaeological Science. 144: 105627. Bibcode:2022JArSc.144j5627R. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2022.105627. ISSN 0305-4403.

- ^ Li, Yu; Gao, Mingjun; Zhang, Zhansen; Duan, Junjie; Xue, Yaxin (2023-04-01). "Phased human-nature interactions for the past 10 000 years in the Hexi Corridor, China". Environmental Research Letters. 18 (4): 044035. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/acc87b. ISSN 1748-9326.

- ^ Xinying, Zhou; Xiaoqiang, Li; Dodson, John; Keliang, Zhao; Atahan, Pia; Nan, Sun; Qing, Yang (2012-03-16). "Land degradation during the Bronze Age in Hexi Corridor (Gansu, China)". Quaternary International. Holocene Vegetation Dynamics and Human Impact: Agricultural Activities and Rice Cultivation in East Asia II. 254: 42–48. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2011.06.046. ISSN 1040-6182.

- ^ Li, Yu; Zhang, Zhansen; Zhou, Xueru; Gao, Mingjun; Li, Haiye; Xue, Yaxin; Duan, Junjie (2023-05-01). "Paleo-environmental changes and human activities in Shiyang River Basin since the Late Glacial". Chinese Science Bulletin. doi:10.1360/TB-2022-0965. ISSN 0023-074X.

- ^ a b "Dunhuang History". Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- ^ Liu, Jinbao (25 March 2022). The General Theory of Dunhuang Studies. Springer Nature. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-981-16-9073-0.

- ^ Komissarov, S.A (2017). "Shajing Culture (Gansu, China): Main Sites and Problems of Chronology". Paeas.ru.

The Shajing culture of the Early Iron Age. The sites of this culture have been discovered in the central part of Gansu Province (China). Seven big burial grounds and almost the same amount of fortified settlements (with walls made of compacted loess) have been excavated. Painted pottery, associated with the local tradition of Neolithic-Early Bronze Age, has been found at the early sites, but the Scythian-like artifacts constitute the core of this culture. This makes it possible to clarify the chronological limits of the culture as 900-400 BC, but probably with the later specific dates. Different suggestions have been made concerning the ethnic origins of the "Shajing people," who may have some connections with the Tocharian-speaking Yuezhi, the proto-Tibetean Qiang and Rong, or even with the Iranian Wusuns. The Shajing culture might have emerged from the interaction of all these (or close) ethnic and cultural components.

- ^ Barnes (2007), p. 63.

- ^ Zhihong Wang, Dust in the Wind: Retracing Dharma Master Xuanzang's Western Pilgrimage, 經典雜誌編著, 2006 ISBN 9868141982

- ^ Youli Li; Jingchun Yang; Lihua Tan; Fengjun Duan (July 1999). "Impact of tectonics on alluvial landforms in the Hexi Corridor, Northwest China". Geomorphology. 28 (3–4): 299–308. Bibcode:1999Geomo..28..299L. doi:10.1016/S0169-555X(98)00114-7.

- ^ "The Silk Roads and Eurasian Geography". Retrieved 2007-08-06.

Sources

[edit]- Barnes, Ian (2007). Mapping History: World History. London: Cartographica. ISBN 978-1-84573-323-0.

- Yap, Joseph P. (2009), Wars With The Xiongnu: A Translation From Zizhi tongjian. AuthorHouse, ISBN 978-1-4490-0605-1.

- Yap, Joseph P. (2019), The Western Regions Xiongnu and Han: From the Shiji, Hanshu and Hou Hanshu. ISBN 978-1-79282-915-4