George M. Cohan

George M. Cohan | |

|---|---|

Cohan in 1918 | |

| Born | George Michael Cohan July 3, 1878 Providence, Rhode Island, U.S. |

| Died | November 5, 1942 (aged 64) New York City, U.S. |

| Occupations |

|

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 4, including Mary and Helen |

George Michael Cohan (July 3, 1878[1] – November 5, 1942) was an American entertainer, playwright, composer, lyricist, actor, singer, dancer and theatrical producer.

Cohan began his career as a child, performing with his parents and sister in a vaudeville act known as "The Four Cohans". Beginning with Little Johnny Jones in 1904, he wrote, composed, produced, and appeared in more than three dozen Broadway musicals. Cohan wrote more than 50 shows and published more than 300 songs during his lifetime, including the standards "Over There", "Give My Regards to Broadway", "The Yankee Doodle Boy" and "You're a Grand Old Flag". As a composer, he was one of the early members of the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP). He displayed remarkable theatrical longevity, appearing in films until the 1930s and continuing to perform as a headline artist until 1940.

Known in the decade before World War I as "the man who owned Broadway", he is considered the father of American musical comedy.[2] His life and music were depicted in the Oscar-winning film Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942) and the 1968 musical George M!. A statue of Cohan in Times Square, New York City, commemorates his contributions to American musical theatre.[3]

Early life

[edit]

Cohan was born in 1878 in Providence, Rhode Island, to Irish Catholic parents. A baptismal certificate from St. Joseph's Roman Catholic Church (which gave the wrong first name for his mother) indicated that Cohan was born on July 3, but he and his family always insisted that he had been "born on the Fourth of July!"[1][4] His parents were traveling vaudeville performers, and he joined them on stage while still an infant, first as a prop, learning to dance and sing soon after he could walk and talk.[citation needed]

Cohan started as a child performer at age 8, first on the violin and then as a dancer.[5] He was the fourth member of the family vaudeville act called The Four Cohans, which included his father Jeremiah "Jere" (Keohane) Cohan (1848–1917),[6] mother Helen "Nellie" Costigan Cohan (1854–1928) and sister Josephine "Josie" Cohan Niblo (1876–1916).[1] In 1890, he toured as the star of a show called Peck's Bad Boy[5] and then joined the family act. The Four Cohans mostly toured together from 1890 to 1901. Cohan and his sister made their Broadway debuts in 1893 in a sketch called The Lively Bootblack. Temperamental in his early years, he later learned to control his frustrations. During these years, he originated his famous curtain speech: "My mother thanks you, my father thanks you, my sister thanks you, and I thank you."[5]

As a child, Cohan and his family toured most of the year and spent summer vacations from the vaudeville circuit at his grandmother's home in North Brookfield, Massachusetts, where he befriended baseball player Connie Mack.[7] The family generally gave a performance at the town hall there each summer, and Cohan had a chance to gain some more normal childhood experiences, like riding his bike and playing sandlot baseball. His memories of those happy summers inspired his 1907 musical 50 Miles from Boston, which is set in North Brookfield and contains one of his most famous songs, "Harrigan". As he matured through his teens, he used the quiet summers there to write. When he returned to the town in the cast of Ah, Wilderness! in 1934, he told a reporter "I've knocked around everywhere, but there's no place like North Brookfield."[8]

Career

[edit]Early career

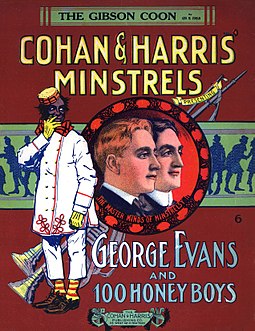

[edit]Cohan began writing original skits (over 150 of them) and songs for the family act in both vaudeville and minstrel shows while in his teens.[5] Soon he was writing professionally, selling his first songs to a national publisher in 1893. In 1901 he wrote, directed and produced his first Broadway musical, The Governor's Son, for The Four Cohans.[5] His first big Broadway hit in 1904 was the show Little Johnny Jones, which introduced his tunes "Give My Regards to Broadway" and "The Yankee Doodle Boy".[9]

Cohan became one of the leading Tin Pan Alley songwriters, publishing upwards of 300 original songs[2] noted for their catchy melodies and clever lyrics. His major hit songs included:

- "Give My Regards to Broadway"

- "You're a Grand Old Flag"

- "Forty-Five Minutes from Broadway"

- "Mary Is a Grand Old Name"

- "The Warmest Baby in the Bunch"

- "Life's a Funny Proposition After All"

- "I Want To Hear a Yankee Doodle Tune"

- "You Won't Do Any Business if You Haven't Got a Band"

- "The Small Town Gal"

- "I'm Mighty Glad I'm Living, That's All"

- "That Haunting Melody"

- "Always Leave Them Laughing When You Say Goodbye"

- "Over There", America's most popular World War I song,[5] was recorded by Nora Bayes, Enrico Caruso, and others.[10] The song reached such currency among troops and shipyard workers that a ship was named "Costigan" after Cohan's grandfather, Dennis Costigan. During the christening, "Over There" was played.[11]

From 1904 to 1920, Cohan created and produced over 50 musicals, plays and revues on Broadway together with his friend Sam H. Harris.[5][12] Aside from the plays Cohan wrote or composed, he produced with Harris, among others, many of which were adapted for film, It Pays to Advertise (1914) and the successful Going Up in 1917, which became a smash hit in London the following year.[13] His shows ran simultaneously in as many as five theatres. One of Cohan's most innovative plays was a dramatization of the mystery Seven Keys to Baldpate in 1913, which baffled some audiences and critics but became a hit.[14] Cohan further adapted it as a film in 1917, and it was adapted for film six more times, as well as for TV and radio.[15] He dropped out of acting for some years after his 1919 dispute with Actors' Equity Association.[5]

In 1912 Cohan and Harris acquired Chicago's Grand Opera House and renamed the theatre "George M. Cohan's Grand Opera House". It was renamed "Four Cohans Theatre" in 1926 but reverted to Grand Opera House in 1928 when Cohan divested the property and the Shubert family became the sole owners of the theatre.[16]

In 1925, he published his autobiography Twenty Years on Broadway and the Years It Took to Get There.[17]

Later career

[edit]

Cohan appeared in 1930 in The Song and Dance Man, a revival of his tribute to vaudeville and his father.[5] In 1932, he starred in a dual role as a cold, corrupt politician and his charming, idealistic campaign double in the Hollywood musical film The Phantom President. The film co-starred Claudette Colbert and Jimmy Durante, with songs by Rodgers and Hart, and was released by Paramount Pictures. He appeared in some earlier silent films but he disliked Hollywood production methods and only made one other sound film, Gambling (1934), based on his own 1929 play and shot in New York City. A critic called Gambling a "stodgy adaptation of a definitely dated play directed in obsolete theatrical technique".[18] It is considered a lost film.[19]

By the 1930s, Cohan walked in and out of retirement.[20] He earned acclaim as a serious actor in Eugene O'Neill's only comedy Ah, Wilderness! (1933) and in the role of a song-and-dance President Franklin D. Roosevelt in Rodgers and Hart's musical I'd Rather Be Right (1937). The same year, he reunited with Harris to produce a play titled Fulton of Oak Falls, starring Cohan. His final play, The Return of the Vagabond (1940), featured a young Celeste Holm in the cast.[21]

In 1940, Judy Garland played the title role in a film version of his 1922 musical Little Nellie Kelly. Cohan's mystery play Seven Keys to Baldpate was first filmed in 1916 and has been remade seven times, most recently as House of the Long Shadows (1983), starring Vincent Price. In 1942, a musical biopic of Cohan, Yankee Doodle Dandy, was released, and James Cagney's performance in the title role earned the Best Actor Academy Award.[22] The film was privately screened for Cohan as he battled the last stages of abdominal cancer, and he commented on Cagney's performance: "My God, what an act to follow!"[23] Cohan's 1920 play The Meanest Man in the World was filmed in 1943 with Jack Benny.[24]

Legacy

[edit]Although Cohan is mainly remembered for his songs, he became an early pioneer in the development of the "book musical", using his engaging libretti to bridge the gaps between drama and music. More than three decades before Agnes de Mille choreographed Oklahoma! Cohan used dance not merely as razzle-dazzle, but to advance the plot. Cohan's main characters were "average Joes and Janes" who appealed to a wide American audience.[25]

In 1914, Cohan became one of the founding members of ASCAP.[20] Although Cohan was known as generous to his fellow actors in need,[5] in 1919, he unsuccessfully opposed a historic strike by Actors' Equity Association, for which many in the theatrical professions never forgave him. Cohan opposed the strike because in addition to being an actor in his productions, he was also the producer of the musical that set the terms and conditions of the actors' employment. During the strike, he donated $100,000 (equal to $1,757,390 today) to finance the Actors' Retirement Fund in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. After Actors' Equity was recognized, Cohan refused to join the union as an actor, which hampered his ability to appear in his own productions. Cohan sought a waiver from Equity allowing him to act in any theatrical production. In 1930, he won a law case against the Internal Revenue Service that allowed the deduction, for federal income tax purposes, of his business travel and entertainment expenses, even though he was not able to document them with certainty. This became known as the "Cohan rule" and frequently is cited in tax cases.[26]

Cohan wrote numerous Broadway musicals and straight plays in addition to contributing material to shows written by others – more than 50 in all – many of which were made into films.[5] His shows included:

|

|

Cohan was called "the greatest single figure the American theatre ever produced – as a player, playwright, actor, composer and producer".[5] On May 1, 1940, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt presented him with the Congressional Gold Medal for his contributions to World War I morale, in particular with the songs "You're a Grand Old Flag" and "Over There".[28] Cohan was the first person in any artistic field selected for this honor, which previously had gone only to military and political leaders, philanthropists, scientists, inventors, and explorers.

In 1959, at the behest of lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II, a $100,000 bronze statue of Cohan was dedicated in Duffy Square (the northern portion of Times Square) at Broadway and 46th Street in Manhattan. The 8-foot bronze remains the only statue of an actor on Broadway.[3][29] He was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1970.[20] His star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame is located at 6734 Hollywood Boulevard.[30] Cohan was inducted into the Long Island Music Hall of Fame on October 15, 2006.[31]

The United States Postal Service issued a 15-cent commemorative stamp honoring Cohan on the anniversary of his centenary, July 3, 1978. The stamp depicts both the older Cohan and his younger self as a dancer, with the tag line "Yankee Doodle Dandy". It was designed by Jim Sharpe.[32] In 1999, Captain Kenneth R. Force and the United States Merchant Marine Academy Regimental Band led a successful effort to preserve Cohan's home on Long Island.[33][34] As a result, Cohan's family gave the Merchant Marine Academy Regimental Band the name "George M. Cohan's Own".[34] On July 3, 2009, a bronze bust of Cohan, by artist Robert Shure, was unveiled at the corner of Wickenden and Governor Streets in Fox Point, Providence, a few blocks from his birthplace. The city renamed the corner the George M. Cohan Plaza and announced an annual George M. Cohan Award for Excellence in Art & Culture. The first award went to Curt Columbus, the artistic director of Trinity Repertory Company.[35]

Personal life

[edit]

From 1899 to 1907, Cohan was married to Ethel Levey (1881–1955; born Grace Ethelia Fowler[36]), a musical comedy actress and dancer. Levey and Cohan had a daughter, actress Georgette Cohan Souther Rowse (1900–1988).[37] Levey joined the Four Cohans when Cohan's sister Josie married, and she starred in Little Johnny Jones and other Cohan works. In 1907, Levey divorced Cohan on grounds of adultery.[38]

In 1908, Cohan married Agnes Mary Nolan (1883–1972), who had been a dancer in his early shows; they remained married until his death. They had two daughters and a son. The eldest was Mary Cohan Ronkin, a cabaret singer in the 1930s, who composed incidental music for her father's play The Tavern. In 1968, Mary supervised musical and lyric revisions for the musical George M![39][40] Their second daughter was Helen Cohan Carola, a film actress, who performed on Broadway with her father in Friendship in 1931.[41][42] Their youngest child was George Michael Cohan, Jr. (1914–2000), who graduated from Georgetown University and served in the entertainment corps during World War II. In the 1950s, George Jr. reinterpreted his father's songs on recordings, in a nightclub act, and in television appearances on the Ed Sullivan and Milton Berle shows. George Jr.'s only child, Michaela Marie Cohan (1943–1999), was the last descendant named Cohan. She graduated with a theater degree from Marywood College in Pennsylvania in 1965. From 1966 to 1968, she served in a civilian Special Services unit in Vietnam and Korea.[43] In 1996, she stood in for her ailing father at the ceremony marking her grandfather's induction into the Musical Theatre Hall of Fame at New York University.[5] Cohan was a devoted baseball fan, regularly attending games of the former New York Giants.[5]

Death

[edit]Cohan died of bladder cancer[44] at the age of 64 on November 5, 1942, at his Manhattan apartment on Fifth Avenue, surrounded by family and friends.[5] His funeral was held at St. Patrick's Cathedral, New York, and was attended by thousands of people, including five governors of New York, two mayors of New York City and the Postmaster General. The honorary pallbearers included Irving Berlin, Eddie Cantor, Frank Crowninshield, Sol Bloom, Brooks Atkinson, Rube Goldberg, Walter Huston, George Jessel, Connie Mack, Joseph McCarthy, Eugene O'Neill, Sigmund Romberg, Lee Shubert and Fred Waring.[45] Cohan was interred at Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City, in a private family mausoleum he had erected a quarter century earlier for his sister and parents.[5]

In popular culture

[edit]

- James Cagney played Cohan in the 1942 biopic Yankee Doodle Dandy and in the 1955 film The Seven Little Foys. Cagney won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance in Dandy.[22]

- Mickey Rooney played Cohan in Mr. Broadway, a television special broadcast on May 11, 1957. The same month, Rooney released a 78 RPM record featuring Rooney singing Cohan's best-known songs on the A-side.

- Joel Grey starred on Broadway as Cohan in the musical George M! (1968), which was adapted into a television special in 1970.

- Allan Sherman sang a parody-medley of three Cohan tunes on an early album: "Barry (That'll Be the Baby's Name)"; "H-o-r-o-w-i-t-z"; and "Get on the Garden Freeway" to the tune of "Mary's a Grand Old Name", "Harrigan" and "Give My Regards to Broadway", respectively.

- Chip Deffaa created a one-man show about the life of Cohan called George M. Cohan Tonight!, which first ran Off-Broadway at the Irish Repertory Theatre in 2006 with Jon Peterson as Cohan.[46] Deffaa has written and directed five other plays about Cohan.[47]

Filmography

[edit]Cohan acted in the following films:[48]

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1917 | Broadway Jones | Broadway Jones | Lost film |

| Seven Keys to Baldpate | George Washington Magee | ||

| 1918 | Hit-The-Trail Holliday | Billie Holiday | Lost film |

| 1932 | The Phantom President | Theodore K. Blair/Peeter J. 'Doc' Varney | |

| 1934 | Gambling | Al Draper |

Gallery

[edit]-

"Over There" sheet music cover (1917)

-

Poster for Seven Keys to Baldpate (1917)

-

Sheet music for Little Nellie Kelly (1922)

-

Caricature by Ralph Barton, 1925

See also

[edit]- Broadway theater

- List of playwrights from the United States

- List of Songwriters Hall of Fame inductees

- Musical theater

- Tin Pan Alley

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ a b c Kenrick, John. "George M. Cohan: A Biography". Musicals101.com (2004), retrieved April 15, 2010

- ^ a b Benjamin, Rick. "The Music of George M. Cohan", Liner notes to You're a Grand Old Rag – The Music of George M. Cohan, New World Records

- ^ a b Mondello, Bob. "George M. Cohan, 'The Man Who Created Broadway', Was an Anthem Machine", NPR, December 20, 2018, accessed July 14, 2019

- ^ Heroux, Gerard H. "George M. Cohan, 2013 Inductee: The Rhody Colossus", Rhode Island Music Hall of Fame Historical Archive, 2013, accessed February 16, 2016

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Obituary: George M. Cohan, 64, Dies at Home Here". The New York Times, November 6, 1942. Archived from original on January 10, 2017

- ^ Cullen, Frank; Hackman, Florence; and Neilly, Donald (eds.). Vaudeville, Old & New: An Encyclopedia of Variety Performers in America, p. 243

- ^ Macht, Norman L. "Connie Mack and the Early Years of Baseball", University of Nebraska Press, 2007, pp. 20 and 342 ISBN 0803209908

- ^ "Give My Regards to North Brookfield: Creator of 'Yankee Doodle Dandy' Called Family Vacation Spot 'Home'", Telegram & Gazette, Worcester, Massachusetts, July 2, 2000, accessed July 23, 2014 (fee required)

- ^ Kenrick, John. "Cohan Bio: Part II: Little Johnny Jones". Musicals101.com (2002), retrieved April 15, 2010

- ^ Duffy, Michael. "Vintage Audio – Over There", FirstWorldWar.com, August 22, 2009, accessed July 12, 2013

- ^ Hurley, Edward N. "Chapter IX: Hog Island", The Bridge to France, J. B. Lippincott Company (1927) LCCN 27-11802 accessed August 29, 2015

- ^ "Cohan & Harris". Internet Broadway Database listing, ibdb.com, accessed April 19, 2010

- ^ "Over There, 1910–1920" Archived 2023-04-23 at the Wayback Machine, Talkinbroadway.com, retrieved April 15, 2010

- ^ Bruscini, Veronica. "Seven Keys to Baldpate", BroadwayWorld.com, January 31, 2014, accessed January 28, 2022

- ^ Warburton, Eileen. "Keeper of the Keys to Old Broadway: Geroge [sic] M. Cohan's Seven Keys to Baldpate (1913)", 2nd Story Theatre, January 32, 2014

- ^ Schiecke, Konrad. pp. 50–56

- ^ "Twenty Years on Broadway and the Years It Took To Get There". Listing at openlibrary.org, retrieved April 15, 2010

- ^ Koszarski, pp. 283–284

- ^ McCabe, p. 229

- ^ a b c "George M. Cohan" Archived 2009-11-18 at the Wayback Machine. Songwritershalloffame.org, retrieved April 15, 2010

- ^ Kenrick, John. "Cohan Bio: Part III: Comebacks". Musicals101.com, retrieved April 15, 2010

- ^ a b Fisher, James. p. 167

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942)", RogerEbert.com, July 5, 1998, accessed July 4, 2011

- ^ Maltin, Leonard. The Meanest Man in the World (1943), Leonard Maltin Classic Movie Guide via TCM.com, accessed July 17, 2018

- ^ Hischak, Thomas S. Boy Loses Girl ISBN 0-8108-4440-0

- ^ "George M. Cohan, Petitioner v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, Respondent" Archived 2009-07-18 at the Wayback Machine. United States Circuit Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, 39 F.2d 540 (March 3, 1930), retrieved April 22, 2010

- ^ "Cohan's "Popularity" a Hit". The New York Times. September 11, 1906. p. 7. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ^ "The George Cohan Congressional Gold Medal", History, Art & Archives: United States House of Representatives, accessed July 5, 2018

- ^ "George M. Cohan Statue". New York City Parks Department site, Nycgovparks.org, accessed April 19, 2010

- ^ "George M. Cohan star location"[permanent dead link]. Hollywoodchamber.net.vhost.zerolag.com, retrieved April 15, 2010

- ^ "George M. Cohan" Archived 2010-09-08 at the Wayback Machine. Limusichalloffame.org, retrieved April 15, 2010

- ^ "Many Honor Patriot Cohan". Spokane Daily Chronicle, July 4, 1978

- ^ Traub, Alex (2023-10-20). "Kenneth Force, the 'Toscanini of Military Marching Bands', Dies at 83". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-04-12.

- ^ a b "Village Makes Cohan Home A Landmark". The New York Times. Associated Press. 1999-12-16. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-04-14.

- ^ Dujardin, Richard C. "Sculpture of Providence native George M. Cohan is unveiled in Fox Point". The Providence Journal, July 4, 2009, accessed April 19, 2010

- ^ Cullen, Frank. "Ethel Levey", Vaudeville Old & New, p. 679, Psychology Press (2004) ISBN 0415938538

- ^ Kenrick, John. "George M. Cohan: A Biography", Musicals101.com, 2014, accessed December 27, 2015

- ^ Levey remained a popular vaudeville headliner and raised Georgette on her own. See Kenrick, John. "Cohan Bio: Part II", Musicals101.com, 2014, accessed July 6, 2015

- ^ "Mary Cohan Finally Elopes and Marries George Ranken", St. Petersburg Times, March 7, 1940

- ^ George M! Archived 2011-10-01 at the Wayback Machine Tams-witmark.com, retrieved April 15, 2010

- ^ "Helen Cohan", Internet Broadway Database, retrieved April 15, 2010

- ^ "Helen Cohan", Internet Movie Database, retrieved April 15, 2010

- ^ Cook, Louise. "Michaela Cohan", The Free Lance Star, October 25, 1968

- ^ Friedrich, Otto. p. 130

- ^ Miller, Tom. "The George M. Cohan Statue – Duffy Square", Daytonian in Manhattan, January 8, 2014, accessed July 23, 2017

- ^ George M. Cohan Tonight! Archived 2012-10-11 at the Wayback Machine on the Internet Off-Broadway Database

- ^ "George M. Cohan Shows". Georgemcohan.org, accessed 16 August 2010

- ^ "George M. Cohan | American composer and dramatist". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-09-22.

Bibliography

- Fisher, James (2011). Historical Dictionary of Contemporary American Theater: 1930-2010. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810879508.

- Friedrich, Otto (1997). City of Nets: A Portrait of Hollywood in the 1940's (1. California Paperback Printing ed.). Berkeley, Calif.: Univ. of California Press. ISBN 978-0520209497.

- Konrad Schiecke (2011). "1875 Coliseum; 1878 Hamlin's Theatre; 1880 Grand Opera House; 1912 George M. Cohan's Grand Opera House; 1926 Four Cohans; 1942 RKO Grand Theatre". Downtown Chicago's Historic Movie Theatres. McFarland & Company. ISBN 9780786488650.

- Koszarski, Richard (2008). Hollywood On the Hudson: Film and Television in New York from Griffith to Sarnoff. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-4552-3.

- McCabe, John: George M. Cohan. The Man Who Owned Broadway (New York: Doubleday & Co., 1973)

Further reading

- Cohan, George M.: Twenty Years on Broadway (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1924)

- Gilbert, Douglas: American Vaudeville. Its Life and Times (New York: Dover Publications, 1963)

- Jones, John Bush: Our Musicals, Ourselves. A Social History of the American Musical Theatre (Lebanon, NH: Brandeis University Press, 2003)

- Morehouse, Ward: George M. Cohan. Prince of the American Theater (Philadelphia & New York: J. B. Lippincott Co., 1943)

External links

[edit]- George M. Cohan at IMDb

- George M. Cohan at the Internet Broadway Database

- George M. Cohan at Internet off-Broadway Database

- Works by George M. Cohan at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- George M. Cohan In America's Theater

- George M. Cohan on musicals101.com

- F. Gwynplaine MacIntyre, "Dancing after retirement: Cohan plays Roosevelt, 1937", New York Daily News, March 20, 2004. [1]

- Chip Deffaa's extensive George M. Cohan site

- George M. Cohan; PeriodPaper.com c. 1910

- Finding aid for the Edward B. Marks Music Co. Collection on George M. Cohan, 1901–1968 at the Museum of the City of New York Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- George M. Cohan recordings at the Discography of American Historical Recordings

- George M. Cohan

- 1878 births

- 1942 deaths

- 19th-century American dramatists and playwrights

- 19th-century American male actors

- 19th-century American male writers

- 19th-century American singers

- 20th-century American dramatists and playwrights

- 20th-century American male actors

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American singers

- Male actors from Providence, Rhode Island

- American male child actors

- American male dancers

- American male dramatists and playwrights

- American male film actors

- American male musical theatre actors

- American male silent film actors

- American male singers

- American male songwriters

- American male stage actors

- American musical theatre composers

- American musical theatre directors

- American people of Irish descent

- American tap dancers

- American theatre directors

- Broadway composers and lyricists

- Broadway theatre directors

- Broadway theatre producers

- Burials at Woodlawn Cemetery (Bronx, New York)

- Catholics from Massachusetts

- Catholics from Rhode Island

- Cohan family

- Congressional Gold Medal recipients

- Deaths from cancer in New York (state)

- Eccentric dancers

- Male musical theatre composers

- Musicians from Providence, Rhode Island

- People from North Brookfield, Massachusetts

- American vaudeville performers

- Writers from Providence, Rhode Island

- Members of The Lambs Club